The world’s last wilderness areas are rapidly disappearing.

A researcher from the University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC) along with a team of international scientists are calling for international conservation targets to protect those last truly wild spaces.

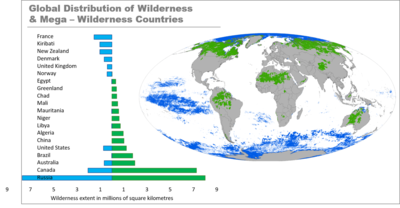

Infographic from Protect the Last of the Wild published in Nature (via UNBC).

Infographic from Protect the Last of the Wild published in Nature (via UNBC). “As we started to map where wilderness actually remains, we found out there is very little wilderness actually remaining,” says Dr. Oscar Venter, an ecosystem science and management associate professor at UNBC.

Venter and his co-authors recently published a study in the journal Nature, which links the two research efforts to provide the first full global picture of how little wilderness remains.

“There is this idea that wilderness is extensive and it’s far from people and because of that, it’s safe and we don’t have to worry so much about it,” says Venter, adding he was alarmed at the results of their research.

The study found that a century ago, only 15 per cent of the Earth’s surface was used by humans to grow crops and raise livestock. Today, more than 77 per cent of land — excluding Antarctica — and 87 per cent of the ocean has been modified by the direct effects of human activities.

“There is only 23 per cent of land and 13 per cent of the oceans that can still be considered as wilderness and that decline is persisting; we are still losing wilderness today,” Venter tells PrinceGeorgeMatters.

He says that unless we do something differently, we are at risk of losing these last remaining intact wild places.

“The idea that wilderness is inherently safe and will always be there for us — that is really not true. We need to start thinking more strategically about how we use the environment around us and how we use Canada’s land base and oceanscapes.”

Venter says the remaining wilderness spaces are important ecologically as they are last places that have a natural assemblage of species and are important places for combating climate change.

“Think about the boreal forest that is one of our biggest intact ecosystems around the world and it stores a huge amount of carbon which would otherwise be released in the atmosphere,” explains Venter, noting wilderness is also important for the livelihood of Indigenous peoples.

The authors of the study are calling for international policy to recognize the importance of wilderness, as national legislation in most countries does not formally define or protect wilderness.

“What we are really calling for in this paper is international recognition of wilderness values in important conventions,” says Venter.

He adds they are calling on wilderness to be included in the post-2020 conservation targets which will be set at the UN Biodiversity Conference held later this month in Egypt.

“Once wilderness is gone — there is still ecological values there — but you are not going to get back to that natural state.”