Nazi propaganda is being purchased on bookstore shelves in Prince George, translated into English by a local publishing company.

It is actually the second translation for the 60-page booklet, minus the modern introduction by acclaimed Prince George author and literary scholar John Harris. It was written originally into Danish and spread around the agricultural communities of Denmark during the German occupation of that country from 1940 to 1945.

Carl Aastrup's father Vilhelm and mother Hilda Johansen received a copy of the booklet entitled The Farmer's Chances if the Axis Powers Lose. It got mingled into Aastrup's books when he moved to Canada, and when he came across it in his elder years, during a move into Prince George from his longtime farm in the Buckhorn area, it brought back a blitz of memories.

"At that time you worked young, eh, so I was out on the farm and I will never forget that day," said Aastrup, recalling April 9, 1940. He was 15 at the time. "It was really cloudy but through the fog I could hear this amazing noise. When I got back to the house I asked about it and my father said it was the Germans arriving. Then when the fog lifted, oh, all the planes. So many planes."

Germany considered Denmark a little-brother nation, based on their occupation behaviour and documents found after the Second World War. Their invasion was benevolent compared to other borders they violated. There was virtually no destruction of property and fewer than 20 Danish soldiers were killed in the initial confrontation, although thousands died in underground resistance fighting or after being conscripted into the German army.

One of the invasion day deaths was Aastrup's neighbour. At the funeral, Aastrup remembers seeing a sleek black car wheel up, smartly dressed Nazi officials get out, and place an opulent wreath on the grave.

"They were doing their PR," he said.

Aastrup's family farm was between the rural communities of Snejbjerg and Albaek, on the western side of the small nation packed tightly between Norway to the north, Sweden to the east and Germany all along its southern border. Due west across the North Sea was the United Kingdom.

The German invasion was partially to take control of a nation it considered practically family but also to set up defenses in case the Allies decided to use Denmark as a channel for a counteroffensive. Aastrup saw the Nazis building roads and digging holes he assumed were for artillery installations and bunkers, should that be necessary.

He also saw the Nazis here and there about town, always on good behaviour. Their uniforms were sharply appointed at first, but grew grubbier as the war went on.

"It was a pretty rotten outfit, the Nazis, there is no two ways about that. That didn't mean all German people - even some German officials - were all bad, though. Not at all," Aastrup said.

"In our everyday lives the Germans would hardly ever interfere, but there was an influence. You couldn't sell meat, that was a rule put on the farmers, and they would send people around to count things up. Usually it was a Danish farmer they got to do the job, and he'd ask 'Vilhelm, how many pigs do you have over there in that pen?' and you'd tell him whatever number you wanted. Or he would go over and count them up and if there was 10, he'd mark down seven or eight, so you'd have a couple of pigs to do with as you pleased, to sell or trade."

The Nazis also littered Denmark with propaganda. Famously, they dropped thousands of "oprop"

leaflets from the sky as they flew in on occupation day. The leaflets called for compliance in exchange for Nazi friendship but the text and even the title was poorly translated (the actual Danish word they had intended was "Opraab" meaning "proclamation").

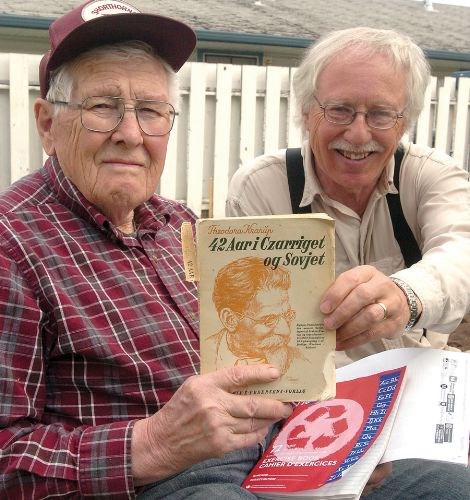

The farmer's booklet was also full of questionable German-Danish translation, said Aastrup, who did not want to repeat that mistake. The booklet arrived at their farm in the mail as many Nazi brochures did and most of it "went into the bloody fire" unread, he said, but this one had more heft to it. He knew the booklet would be interesting to history buffs so he called on Harris, a retired CNC professor who once had a neighbouring Buckhorn farm. Harris was also once a regular publisher of literary works by such Canadian scribe giants as Michael Ondaatje, Al Purdy, Barry McKinnon, and many more under his banner Repository Press.

Harris decided to stamp the now rarely used Repository symbol on this project.

"I was really interested in this," said Harris. "You want to be interested in public affairs, you want to know what people thought, what the conditions then were like. It's good to bring out examples like this, for study and for historical value."

Harris and Aastrup made a project of translating it, paining over choosing the best words to convey not only the literal meaning but also the spirit in which it was intended.

"What was interesting to me was the admission in the title that Germany could lose the war. All you ever heard from them, right up until the very end, was how they were winning," said Aastrup.

"What struck me was their very good description of the agriculture industry under capitalism and the agriculture industry under Bolshevism, but only the worst parts of it, and they didn't go into much detail about how they would do things better," Harris said.

The booklet was an exhaustive argument in favour of Danish farmers fearing both British/American capitalism and Russian Bolshevism as those two forces closed in on the Nazi regime.

The booklet also smeared Jews at several junctures.

"There were only 8,000 or 10,000 Jews in Denmark at the time," said Aastrup. "Most of them lived in Copenhagen and that area, so it was relatively easy for them to get away to Sweden when things became dangerous. But still about 1,000, I think, ended up in concentration camps. I never heard of any persecution of Jews by Danish people, and if there was ever any cultural bias against Jews I never heard of it. That was pretty sad, what was done to them. Pretty sad.

"You don't want to condemn all German people. That's wrong. But you don't want to let the Nazis off easy, either, because they were a terrible, terrible bunch of criminals."

The booklet's English version is now for sale at Books and Company and more than half the original run has already been sold at $2.50 per copy. Harris and Aastrup said this barely covered the cost of printing, but the point of the project was adding value to posterity not their bank accounts.

Now the two are working on another Danish-English translation - a project they refused to discuss publicly yet, but they each had a glint of excitement in their eye.

"When an old Danish peasant runs into a wise English scholar, you never know what happens," said Aastrup with a laugh.