For much longer than the six years Vasiliki Douglas has been teaching an introduction to indigenous health care practices at the College of New Caledonia, she was aware the subject was devoid of resources for educators and their students.

“There really wasn’t anything, any textbook, any collection of materials that we could rely on, so I set myself the task to filling this gap,” said Douglas, who holds a PhD in the history of nursing and has won multiple research grants to study and present on indigenous health research.

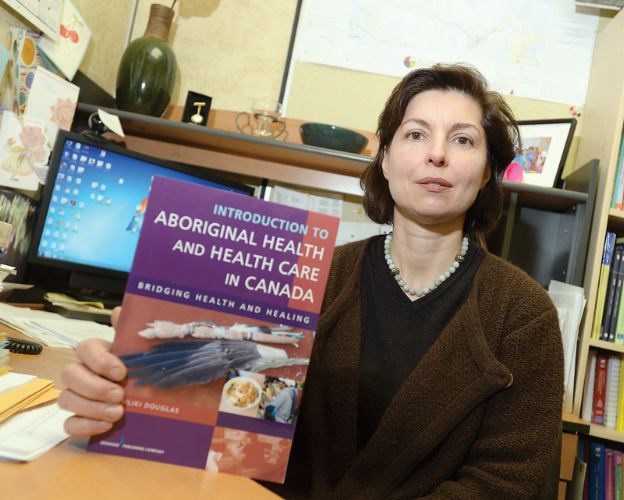

Last spring that gap closed just a little more when her textbook, titled Introduction to Aboriginal Health and Health Care in Canada, was published.

“This textbook, I hope, addresses some of the deficiencies and brings forward some possible solutions for healthcare professionals to consider in partnership with aboriginal peoples.

“Traditional [Canadian] approaches tend to be very, if I may say, didactic, very biomedically focused, very much focused on the physical aspect of health, almost disregarding the spiritual and emotional - and yet they’re so integral to the overall health,” she said, not only of aboriginal peoples but a holistic approach that applies to all patients.

Nurses must also examine the pulse of the past and its impact on present health care realities to help reintroduce the respect that Douglas said is still missing.

“We do have a history in Canada of not reaching out to aboriginal peoples and making a difference in their health,” she said.

It also means knowing that certain illnesses like tuberculosis and diabetes are more prevalent in aboriginal communities.

“This education is a must for professionals working in the north, in remote and rural areas, certainly because of the number of aboriginals living in the north and remote areas,” said Douglas, but also pointed out that as urban aboriginal populations continue to rise, awareness among medical professionals is both relevant and required everywhere.

Douglas said CNC is a leader in that regard, and has made the course a program requirement of its nursing students. That’s not necessarily the case at other institutions, although Douglas points to the University of Victoria and institutions in Ontario for starting to include courses on cultural competency.

In July, the Canadian Nurses Association published a report with the goal of charting a policy direction for nursing in Canada, which detailed the need to integrate indigenous knowledge in health care practices, acknowledged institutional barriers to aboriginal health and identified ways to recruit and retain aboriginal nurses and educators.

It noted: “The integration of indigenous ways of knowing and being was considered by the [report’s] participants in the consultation process to be primary and foundational to all the other priorities and to be the “lens” that integrates the other priorities.

Douglas’s textbook also employs a term that is becoming increasingly relevant in health care and other fields: cultural safety.

“Cultural safety really offers the potential to bridge the divide between aboriginal and non-aboriginal populations in the healthcare system,” said Douglas, whose textbook was a PROSE Award Winner in the category of Nursing and Allied Health Sciences.

“It really deals with the relationship as professionals with patients,” she said, adding that approach inevitably also relies on the practitioner’s personal commitment to cultural sensitivity.

Douglas acknowledged the textbook is a general, even “sweeping,” introduction to indigenous healing in a country that has more than 600 First Nations.

“It really needs to be tailored to the local needs,” said Douglas - and in consultation with aboriginal people “to teach us - we who are not aboriginal - the essence of healing through their eyes, though it will vary from one nation, from one group to another.”