Ten years have passed since the Feb. 1, 2003 avalanche that killed seven Calgary-area high school students while backcountry skiing in Glacier National Park near Rogers Pass.

That year, 29 people died in avalanches in Canada, prompting the federal government to initiate changes to make mountainous areas safer for winter recreational users.

The school tragedy was the catalyst for the establishment of the Canadian Avalanche Centre (CAC), an offshoot of the Canadian Avalanche Association, and led to Parks Canada developing a new terrain classification system that restricts school group access to potentially dangerous areas.

Close to 80 per cent of Canada's avalanche deaths happen in B.C. In November 2011, Dallas Mayert of Prince George died while snowmobiling in the Macgregor Mountains near Upper Torpy River. The 2012-13 avalanche season began early and tragically, on Oct. 23, when surveyor Pat Lawrence Desmarais of Telkwa was swept off a cliff and killed on a mountainside northwest of Stewart. There have been a few close calls since then, but no serious injuries or deaths.

Since the centre was formed 10 years ago, Canada has averaged 14 avalanche deaths each year, although the number of fatalities has dropped off in recent years with 12 deaths reported in 2009-10, 11 in 2010-11 and 10 in 2011-12.

"During the past three winters we've been below that 10-year average for fatalities and that's still the case this year and we'd like to think there's signs of our work paying off," said Joe Lammers, a public avalanche forecaster for the CAC.

"There's been a steady increase in the number of people accessing our website, avalanche.ca, and that's where you can find the avalanche bulletins, as well as up-to-date information on gear selection and the incident report database, and chat forums."

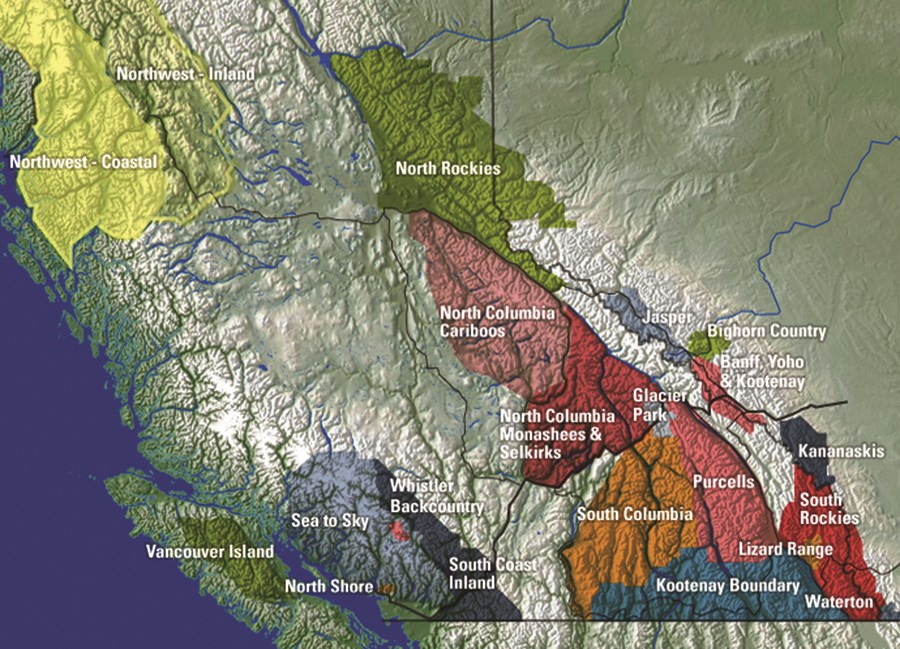

The centre issues weekly avalanche bulletins on Thursdays to cover the North Rockies region east of Prince George, among 16 monitored regions. In all but three of those regions (Northern Rockies, Yukon, and Bighorn in eastern Alberta) bulletins are produced daily. The daily updates are used to determine avalanche area ratings. Reports from professional backcountry outfits such as heliski operators is collected on the association's InfoEx website, which increases the accuracy of the bulletins. Lammers said the centre is looking into the logistics of including the North Rockies in its daily bulletin coverage.

While most deaths recorded in the association's incident report database take place in late February and March, Lammers said there is no safe time of year in avalanche season.

"This is a time of year when weak layers can get created but that's not to say isn't the case in early winter or spring as well," said Lammers. "If there's enough snow to ride, there's enough snow to slide. Some of the weak layers to the east of Prince George got buried by new snow in the fourth week of January. There's about 40 to 70 centimetres of snow on top of those weak layers and that instability adds to the wind slab activity we've been seeing at higher avalanches.

"Wind takes snow off the surface and blows it into deeper pockets on the lee side of ridges and terrain features and the extra weight of all that snow adds more stress to weaker layers and increases the chances and consequences of avalanches."

Lammers, an avid snowmobiler, said education is the most valuable tool any winter backcountry user can arm themselves with before they venture into avalanche areas. He advises checking the most recent bulletins and using common sense on the slopes.

"When you're a snowmobiler covering terrain it's tempting to just stay on the throttle, but it's just as important to stop and discuss slope selection as it is when you're skiing, snowboarding or snowshoeing," Lammers said. "Someone else might be also thinking it's not safe and if you stop you might find out you're not alone.

"I also see with sledders people congregating at the bottom of a slide path and it's really tempting to park your machine and have lunch and watch your buddy high-mark. But there are safe places to do that, on ridge crests or in areas of denser trees, areas far away from potential runouts of avalanche slide paths. Dangerous places would be at the bottom of slopes or in terrain traps, like a ditch feature where debris would pile up."

The CAC sanctions 2 1/2-day avalanche training courses that teach people to recognize dangerous snowpack conditions, how to find safe routes and how to perform rescues. Last year, about 7,000 Canadians took an approved avalanche course, administered by approved contractors.

Having the right equipment is also essential. Lammers says every backcountry user should have their own transceiver emergency beacon, a probe to find a buried person, and a shovel.