When someone tells you jail was safer than school because he wasn’t raped in jail, you know a First Nations Elder is sharing their story.

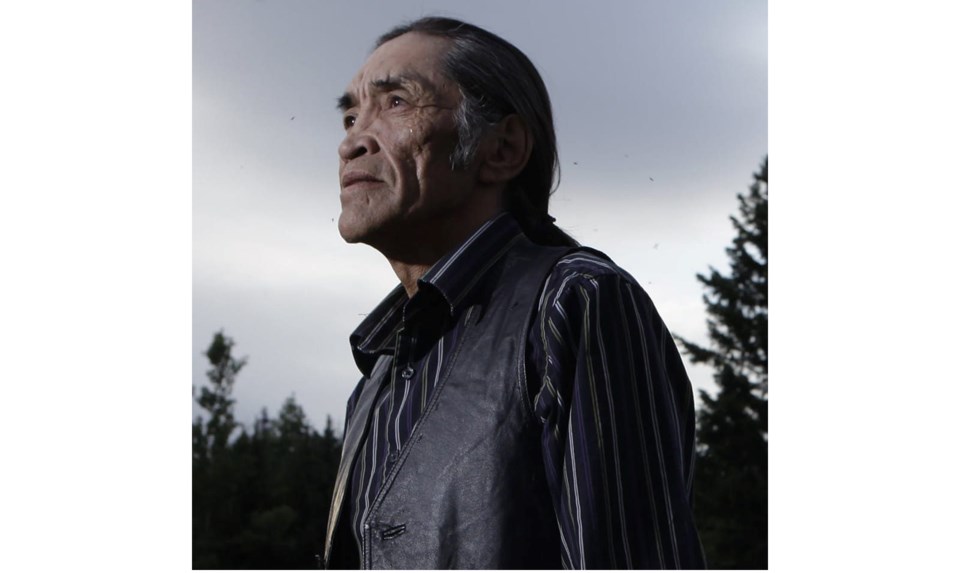

Yekooche Elder Henry Abel Joseph, part of the Dakelh (Carrier) nation, who has seen 70 winters, talks about what the first eight and a half years of his life were like at home, how he fought right from his first week at Lejac residential school which he attended from 1960 to 1968, how what he calls ‘residential school rage’ got him thrown in jail for successfully defending his people on reserve from a drug gang, and how he has come through it all with his language, his culture, his belief in the Creator and the ways of his people still intact.

A big part of Elder Joseph’s healing from trauma is service to the community.

“I go where my heart leads me,” he said.

A fraction of what he does in the community includes helping children lost to the foster care system at the Sk’ai Zeh Yah Centre through Carrier Sekani Family Services by sharing his knowledge of the Carrier culture. Early morning and late-night walks downtown see him regularly checking on his brothers and sisters to let them know he cares. He volunteers his time and energy and knowledge wherever it is needed, including with the UHNBC Drumming Group, advocacy group Together We Stand and with other organizations supporting Moccasin Flats residents and those who are in the Knight’s Inn, that has 44 units geared for supportive housing for those living on the streets.

His residential school experience

When Elder Joseph arrived in residential at eight and a half years old, he already spoke English as his mother was a cook in logging camps and the owner of one of those logging companies provided him with an education.

“I had perfect diction,” he said. “The boss’s wife taught me to read and write and to sing and play musical instruments.”

An older boy picked on him when he first got to Lejac.

“He called me half-breed – ‘hello half-breed, hey white man – why are you here? This is for Indians, he said to me. It really upset me and I went over to him and I just started boxing him because I came from a big family and my parents were well respected.”

A Catholic brother came to break up the fight, pulled the two boys into the centre of the room in front of 100 other boys to be told fighting is against the rules.

“He pulled down our pants – the first strike – the shock – the pain – it’s something I can’t explain,” Elder Joseph said. “It just goes straight through your brain and after a while you get numb to it."

That goes for all the abuse Elder Joseph endured.

"You just try to survive and you’re numb and you go to another place," he explained. "It’s really weird because you’re there and you’re not there. It’s just like it’s happening to somebody else – could this be real? But the pain makes you know it’s real.”

He was left with what he calls residential school rage that was seen often as a traumatized young man trying to navigate in the world.

In his day, Elder Joseph was one of the best kick boxers on the street. It was a matter of survival.

“I was so wounded in residential school and so broken when I got out of it."

Fixing what's broken

“When we all learn to see the same things and appreciate what we have and how much we can share we are more likely to enter into a relationship that gives credence to the idea of reconciliation.

“In the potlatch system, we are all equal to one another and everyone’s word is as important as the others. We sit in a circle and we all share equally whatever we have. There’s honesty, truthfulness and integrity and that has gone on time before time.”

By sharing, teaching and learning, we can all draw closer together by understanding one another, he added.

“That’s how we put our strengths together that benefit everyone and that’s a message by which remedies can be exercised to resolve the social crisis that’s growing in the City of Prince George to house folks, provide services and treat addictions. When we listen to each other, the solutions become clear and the solutions belong to all of us because that is the nature of sharing as the Dakelh people.”

We have all experienced trauma and we have to learn to live with it, he added.

“I visit quite often the downtown core – checking in with my brothers and sisters on the streets – to even just stand there and listen to their story – and to remind them that we do care and that we supply them with hope because they need them to know we love them, and I feel proud to be a member of the advocacy group Together We Stand.

“Through allies with strong hearts, deep concerns, and professional guidance, there are solutions we can find. Mr. PG can be polished up and Prince George can be considered the true hub of the north for all people by proving action to solve the social crisis that won’t go away without it. Social advocacy groups can only do so much so municipal, provincial and federal governments need to take action to help us help each other.”

Looking back and looking ahead

“I would like to say that throughout my life I was gifted with many beliefs and teachings from Elders during my formidable years from when I was born to the time I was eight and a half years old,” Elder Joseph said. “We learned about spirituality.”

When carrying a heavy load far, far, away from home, the family would pray to Grandfather Spider.

“We asked him for his help,” he said. Grandfather Spider would gather the heavy load in his legs.

“And we had no recollection of the hardship in our journey home with the heavy load. And before we knew it we were home with our family having tea. That’s what happens when we pray that way.”

Being grateful to the animals to so important.

“My dad was away and my mom was alone with her grandchildren and they were up the road a mile or two checking rabbit snares. A grizzly bear walked in front of them and my mom talked to that grizzly bear. She said ‘we have an agreement, you and I, we have an understanding to share and I am here to feed my grandchildren,’ and the bear stood up and he made a noise and he walked away into the bushes. And the children witnessed that. We are taught that there is no fear when there is respect.”

The environment is made to be part of the safekeeping culture where things are nurtured, not destroyed.

“We have to take care of our environment because it’s for the children – it’s going to be theirs very soon. At the age I am now I am responsible for the health of our territory, that includes the land and the water.”

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for residential school students and their families. If you are in need of counselling or support call the 24-hour national crisis line at 1-866-925-4419.