The day he punched his first-aid ticket as a treeplanter, the gears of Ryan McMaster's working career were set in motion

As a lifeline to his fellow workers, it began to dawn on him he'd rather nurse people than trees.

McMaster was working in the bush the day he got a call from his wife Wendy to let him know he'd been admitted to the College of New Caledonia as a registered nursing student.

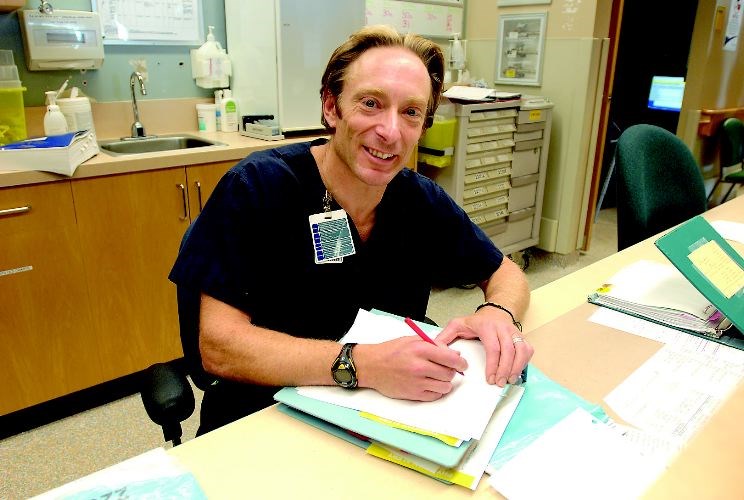

Soon after he started school, McMaster was asked why he wanted to do "women's work" and a few family members wondered why he wasn't studying to be a doctor, but he almost never gets those kinds of questions when he's on the job at UHNBC.

"It's a societal kind of thing, perceptions change," said McMaster. "People see so many more males in nursing, it's becoming more normal."

He's one of eight males working the internal medicine unit at UHNBC among a staff of about 60 nurses. Throughout the Northern Health region there were 135 male nurses working as of January, up from 126 in 2011 and 96 in 2010.

Nurses in B.C. at the top of the pay scale make $40 per hour, working 12-hour shifts. The four-days-on, five-days-off schedule gives the 41-year-old McMaster time off with his wife and two young kids and lots of time to tackle his athletic pursuits -- marathon running, snowshoeing, skiing, and swimming. Like many of his medical colleagues at UHNBC, he practices what he preaches to his patients and is big into eating healthy and maintaining a high level of fitness.

"They really pushed that when they were started recruiting for the four-year RN program at UNBC/CNC and that was appealing for a lot of guys -- a lot of us are pretty athletic kind of guys and word of mouth kind of spread," said McMaster.

In 1999, when he entered the program, hospital recruiters were looking specifically for males to take on nursing positions that involve some grunt work. Four years later, McMaster graduated and was hired to work in rehabilitation, helping patients recover from strokes or joint replacements.

"It was a very physical job, getting people up, dressing them, getting them to lounge where they eat or to the bathroom or to their appointments for occupational therapy," said McMaster.

Compared to most professions, nurses have a higher rate of workplace injuries, most commonly, sprains, strains and tears in the back and joints. Hospital wards are all equipped with lifts that take away some of the strength requirements, but as McMaster found during one of his shifts, there isn't always time to locate that equipment. One of his male patients needed to use the toilet and there wasn't time to find a lift, so McMaster picked him up and carried him to the washroom and then brought him back to bed. He found out later the man weighed 205 pounds.

Several of the males on staff have their Code White certifications which trains them how to deal with aggressive or violent patients and will respond if a situation develops in the hospital.

Bariatric beds are now commonplace in hospitals, built to handle patients as large as 300 kilograms, and when somebody that big needs to be turned in their beds, chances are the male nurses on staff will answer that call.

Nurses are called upon to handle such procedures as a urinary catheterization or washing a private area, and McMaster says it's not unusual for a woman to request a female nurse to carry out that duty.

"Definitely, age is a determining factor, a younger woman might ask for a female to do that and it's no big deal, you just pass it on to one of your colleagues," he said.

The maternity/labour delivery ward is the only part of the hospital staffed strictly with female nurses, although all nursing students serve tours of duty in that department. McMaster knows of one male nurse who tried to break down that barrier and was basically told by the staff that in the best interests of childbearing women he'd be better off choosing another specialty.

Nursing in any department can be a physically-demanding job and the odds are stacked against nurses who aren't in shape for having long careers. After a steady dose of night shifts working in rehab, McMaster was feeling burnt out and decided to switch to internal medicine in 2006.

Being on the frontline of medicine dealing with acutely ill patients is a recipe for stress and nurses have to learn how to deal with it every shift. A caring, empathetic nature is a job requirement and sometimes that means going the extra mile -- phoning long-distance relatives to give a patient update or walking downstairs to buy a family a box of Tim Hortons donuts. Seeing patients regain their health and leave the hospital to go home is all it takes to make McMaster's day.

"I get those interactions with families and patients for a longer time, and being able to be close and personal with families, I've always loved that," he said. "We've lost patients we've cared for over long periods of time and when families thank you for taking care of their loved ones, it's just so gratifying."