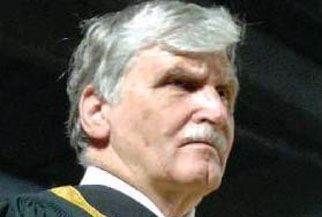

When Romeo Dallaire makes his keynote address at the annual Bob Ewert Memorial Lecture on Saturday, the outspoken advocate can pull from any number of his passion projects.

From humanitarian work to conflict resolution, child soldiers to mental health, and genocide prevention to international aid, the former Canadian general has been busy since he retired from senate in June.

It was focusing on those areas that led to Dallaire's decision to leave after nine years in the upper chamber.

"I left, not by choice, but by taking a deliberate assessment of what I had to accomplish and I simply couldn't do it by staying in the senate," Dallaire said.

That work involves the Child Soldiers Initiative, an organization he founded that focuses on preventing recruitment of children in the school systems and also directly with security forces to stop the child soldiers from being killed.

One of Canada's most famous military figures, Dallaire gained recognition as the UN Commander for the mission in Rwanda.

He defied orders to leave during the 1994 Rwandan genocide, which saw more than 800,000 people killed in less than 100 days.

While his organization is getting "significant buy-in" from both NATO-type countries and also developing countries, it faces barriers because of Canada's actions, he said.

"Canada, first of all, has been incredibly marginalized in anything prevention," said Dallaire, though he sees the country's work with UNICEF as positive.

"Much of the work that I do on child soldiers is undermined by the fact that the government has refused to recognize Omar Khadr as a child soldier," said Dallaire of the Canadian, who pleaded guilty to killing an American soldier in Afghanistan when he was 15.

Khadr has since said he pleaded guilty to the five war crimes in 2010 to get out of Guantanamo Bay, where he'd been detained for a decade.

"When you're sitting in Uganda and you're discussing it and somebody raises it there, it tends to undermine your credibility of trying to get them to change their ways when back hom - being a founding member of that whole optional protocol on child rights - we don't even recognize it," Dallaire said.

So what does Dallaire say to that challenge?

"I respond to it by saying that in my opinion the current government is doing a horribly erroneous response to something that is clearly a child soldier requirement and their unwillingness to recognize that is very specific to the current government," said Dallaire, adding he suggests that approach might change with a shift in government.

The ultimate goal is to change how people approach the concept of child soldiers.

"It's making people realize that child soldiers are not a social-economic problem only, although it's part of it. It is far more, to start with, a security problem."

That involves training police and military as well as different agencies, with a goal of "one, prevent the recruitment and that includes going into school curriculums and two, making them a liability to those who do recruit them when they use them without killing them."

Dallaire is headed to several central African countries in a couple weeks but before his stop in Prince George, he will accept 2015 Calgary Peace Prize.

His experience in Rwanda still haunts him but Dallaire, who has post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), has been a tireless advocate for mental health.

"Somebody who's got a broken arm or physical injury rarely is reticent to speaking about it so why should I be reticent to speak about my injury between my ears?"

The country has made great strides since he was first diagnosed in 1997.

"There was absolutely nothing available," said Dallaire, who said the stigma around mental health has changed considerably.

"We couldn't even approach that subject five years ago."

Now, he said, there is a consciousness that people who do demanding jobs where they face ethical, moral and legal dilemmas, will likely experience trauma.

"Those traumas will injure them and so those injuries have to be handled just as urgently as physical injuries," he said.

One challenge centres on better training for therapists so they can speak the language and understand the experience of first responders, military personnel and even war correspondents, Dallaire said.

"One of the great weaknesses of therapists is that they know their milieu and they know... the civilian worlds, but many of the casualties are those who are wearing uniforms of all types, and not understanding their jargon and not understanding their culture puts (therapists) at a great disadvantage."

Dallaire - who wrote Shake Hands With the Devil and They Fight Like Soldiers, They Die Like Children - will attend a book-signing event at the Bob Harkins branch of the library from 4 p.m. to 5 p.m. before heading to the event at the Prince George Civic Centre.

The Bob Ewert Memorial Lecture is held annually in honour of the city's first medical specialist.