Faced with a society so reliant on technology, the founder of a Canadian group devoted to braille literacy is worried the vision-impaired tool will die out.

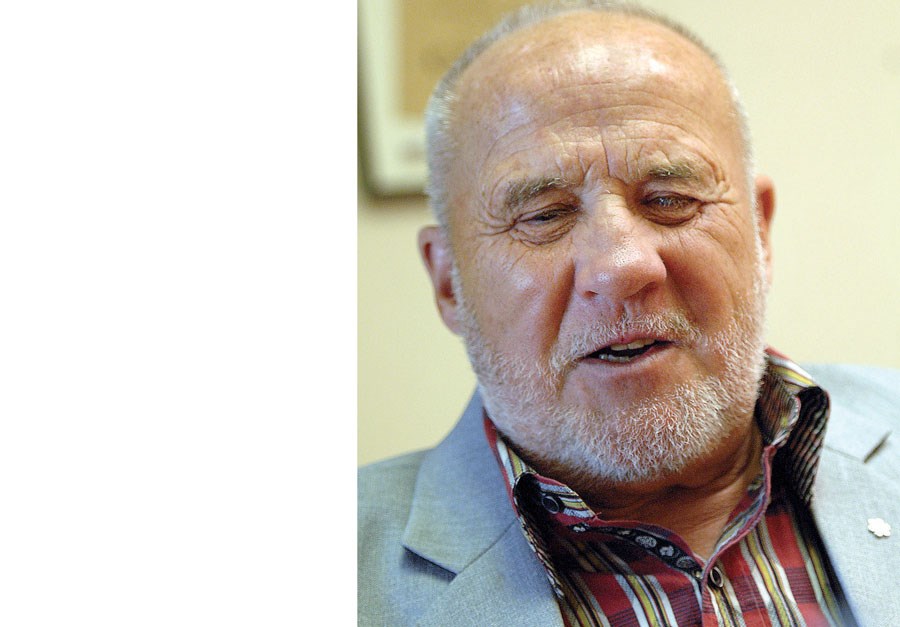

"Braille in the developed world, in Canada, is in crisis because we're not teaching it to young people," said Euclid Herie, president of the World Braille Foundation. Herie is in Prince George this week for the foundation's annual meeting. "I tell people braille and print are not competing languages. It's good to know both. It doesn't hurt."

Prince George resident John Wemyss is on the charity's board and invited the small group to have their annual gathering at the Coast Inn of the North on Tuesday and Wednesday.

The foundation was established in 2001 after Herie retired from leading the Canadian National Institute for the Blind as president and CEO.

"People are using computers and voice access and there are clever blind people - I'm not one of them, I don't use a smartphone... but the thing with that is, that if you can't read you're not going be literate," said Herie.

The foundation focuses on the places in the world where technology is not easily accessible and where the blind are more vulnerable, especially girls and women in rural or remote areas of the developing world.

During this week's meeting, the foundation will award the first Gerald Dirks Scholarship to support inclusive education and advancing employment opportunities for blind adults in Africa. The first recipient is a 30-year-old woman named Josiana from Burkina Faso who will use the $1,000 to finish her education and become a resource teacher for blind students. The foundation has also passed out more than $6,000 in Barbara Marjeram Braille Literacy Awards.

Herie learned first-hand the importance of braille when he was teenager and could no longer function as his sight faded.

"I wasn't blind when I was 15, but I was blind when I was 30. I had cataracts. The point is, if you're not blind when you start out, you're going to end up being blind in many cases because eye diseases are progressive," he said. "So if you don't learn braille and you lose your sight at 40 and you're trying to be a lawyer or teacher or a social worker, how the hell are you going to read and write?"

The World Braille Foundation funds two-year projects in countries such as Kenya, Swaziland and Niger where they set up resource rooms in schools to teach braille and create braille texts to get blind children into the school system. Before they begin, the local governments agree to sustain the programs after the foundation's two-year introduction.

Integrating blind students into regular classrooms is a slow process. When Herie was in Grade 11, he was shipped from his home in Saskatchewan to a Brantford, Ont., school for the blind. That was in the 1950s and it wasn't until the late 1960s/early 1970s that blind children were allowed in mainstream schools in Canada.

"That took 50 years in a developed country," said Herie, who has to convince foreign governments to get on board, especially in places where there are cultural taboos around the blind. "So what I say to the minister of education wherever I am in Africa, well this isn't going to happen in your lifetime or mine, but we've got to start somewhere."