While other dads were doing projects like painting a fence or building a bird feeder, Prince George author Gillian Wigmore's veterinarian father spent his time a little differently.

“My dad really liked this one cow we got because he got to build him a new rectum and he liked that kind of project,” Wigmore said over the phone from her home recently.

Growing up, Wigmore lived in Vanderhoof, where her dad, Walter, was the only vet from 1968 to 2009.

She and her three siblings often had front-row seats, in this case bales of hay, in their dad's operating theatre, which was usually a dark, drafty barn in the middle of nowhere.

“He did have some pretty strict rules. We weren't allowed to ask questions during the call, but afterwards he would answer any questions we had,” Wigmore said. “There was no mucking around.”

She remembers how, for four young kids all within five years of each other, that latter rule was tough.

But there was always a carrot dangled in front of them to encourage good behaviour.

“I remember all four of us sitting on one hay bale and the temptation to punch each other out was so big because we irritated each other so much,” Wigmore said. “We had to be still and we had to be quiet, otherwise we wouldn't get a treat on the way home or we wouldn't get told a story, because my dad was a really big storyteller.”

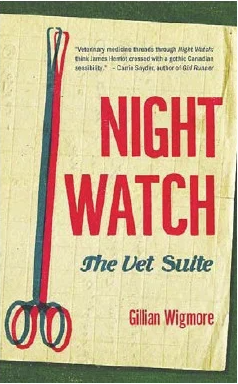

That apple apparently didn't fall far from the back seat of Walter Wigmore's vehicle. Gillian's latest offering, Night Watch: The Vet Suite, collects three novellas centred on the lives of rural vets.

The stories are vivid, entertaining and, of course, a little bit heartbreaking - animals die and human hearts are broken.

Wigmore doesn't sugar-coat her characters. There is no sappy saviour syndrome with these vets, just hard-working, long driving, sleep-deprived animal doctors who have to make tough decisions for themselves and their patients.

The manager of the Prince George Public Library's Nechako branch , Wigmore says with this collection she wanted to look closer at the hows and whys of the rural vet existence.

“I wanted to understand it better. I saw it as a child and there were parts I understood, but what I couldn't really understand is how he (her father) could keep going, because it was so tiring and so demanding,” Wigmore said. “There is passion there, but it seemed superhuman. I can't do that. All I can do is write about it and look at it.”

While looking back, Wigmore saw over and over how her connection to her father's life helped to shape hers. Being the child of a rural vet “was a great way to not be cool,” Wigmore said.

While other kids were doing regular kid stuff, Wigmore was helping her dad do things like get rid of bodies.

“I always helped my dad,” she said. “Tuesday nights we'd take the frozen animals to the beehive burner down the highway because he had a deal with the mill there. He didn't have a crematorium so this is what we would do. We would drive in our tiny Suzuki Samurai out there and put these frozen plastic bags onto a conveyor belt and that's one of the things I did with my dad.”

Later Wigmore, 44, would write about that experience.

“I remember getting to university and writing a poem about that and having people look at me in horror,” said Wigmore, who has an MFA from the University of B.C. and is currently working on a masters of library studies remotely through the University of Alberta. “I mean, I knew it, I knew my growing up was very different than theirs, and it had a pretty profound effect. You know, withfbeing so close to life and death all the time.”

With Night Watch, Wigmore says she was very focused on getting the tough part of the job right.

“One of the reasons I wanted to go into it in detail is because it would drive me crazy when little kids would tell me, when I was a little kid, that they wanted to grow up to be a vet. Because I thought, `You have no idea. You have no idea how gross it is and how much time you are spending looking in a microscope, or driving, or with blood all over you or your hand covered in poop,'” Wigmore said. “Kids always think it is so warm and fuzzy. You get to care for and cuddle bunnies. Sure, but you get to see bunny die too.”

That dark point aside, Night Watch is equal parts cold reality and warm sentiment.