This is an updated version of a column that first appeared in The Citizen on June 8, 2007:

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but pictures, like words, aren't created equally.

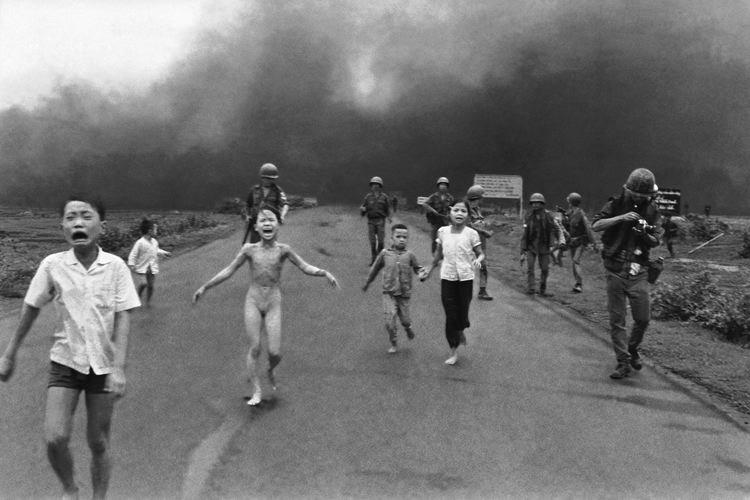

The picture of Kim Phuc, taken on June 8, 1972, in the village of Trang Bang, north of Saigon, Vietnam, isn't constrained by a thousand words or even words at all. Arguably the most famous photograph of civilian suffering during wartime, it crystallizes the pain and agony of war, particularly on children, in one horrific image.

The screams of Phuc and her older brother Tam, in the front left of the frame, are not just piercing wails.

"Nong qua, nong qua," Phuc cried over and over.

Too hot. Too hot.

Tam was shouting for someone to help his sister.

The man behind the lens was Nick Ut, an ambitious Vietnamese photographer whose persistence had led him to a job at the Associated Press bureau in Saigon, first as a darkroom technician and then as an occasional shooter.

Ut and the other photographers had used up their film a few moments earlier when an old woman had stumbled down the road with the burned corpse of a child in her arms. When Phuc, Tam and the other children came down the road minutes later, the photographers were changing rolls of film (one of them can be seen doing so on the right). Ut pulled out the extra camera he kept in his bag for such a moment and captured the image that defined the Vietnamese War.

The other photographers would get pictures of Phuc but from behind, her burns from the napalm already clearly visible across her back and her left arm.

Ut would take Phuc and another victim to the hospital at Cu Chi on the way back to Saigon and literally dropped them off at the front door. He and his driver were afraid to be caught on the highway at night and there was a deadline to meet. Ut spent the drive back into the capital hoping his photos were in focus and properly exposed.

Despite the Associated Press rule of no frontal nudity in news photos, Ut's editors insisted on forwarding the photograph to New York. Under intense deadline pressure, one change was made to the photograph. In an era before Adobe Photoshop and easy digital manipulation of an image, the photo desk staff carefully lightened Phuc's genitals with grey paint because the shadows in the picture suggested pubic hair on the little girl.

On June 9, the photograph appeared on the front page of newspapers across the globe.

Over the next 18 months, Ut would receive virtually every major journalistic award for news photography, including the Pulitzer.

Phuc was initially left to die a painful death. Two days later, her parents found her in a Saigon children's hospital, heavily sedated and kept in a room with other children not expected to survive. Through their begging, Phuc was brought to one of the few specialized burn units in the country, an institution that rarely accepted emergency patients. Only through the pleading of a nurse was Phuc admitted.

The young girl would remain in critical condition for more than a month. Her family was sure she was going to die. Phuc's older sister fainted the first time she saw doctors changing the bandages.

Today, Kim Phuc lives in Toronto. She also has a connection to Prince George.

Former resident Denise Chong told Phuc's story in the 1999 book, The Girl In the Picture, from which much of the above information about that day. It is a compelling read, particularly what happened to Phuc in the 20 years between the photograph and the memorable day she arrived in Canada in 1992.

Phuc will be in Prince George on Saturday, as the guest speaker at the Bob Ewert Memorial Dinner and Lecture, an annual fundraising event for the Northern Medical Programs Trust.

Phuc continues to focus international attention on the plight of children victimized by war.

She has publicly forgiven the men who ordered the bombing of her village. She is an inspiration.

The image of her cruel agony helped change the world.

-- Managing editor Neil Godbout