When Justin Trudeau was first elected prime minister in 2015, his campaign emphasized themes of reconciliation.The Stephen Harper government had sewn racial divisions and animosity; Trudeau promised something different. Appointing the first Indigenous Minister of Justice, Jody Wilson-Raybould, to cabinet, Trudeau proclaimed the inauguration of a renewed relationship between the government and Indigenous peoples.

Six years later, and I (Daniel) am still waiting for my boat house. Trudeau, however, seems to be having a nice time on the beach.

During the 2019 federal election, Daniel wrote an opinion piece for The Camrose Booster, highlighting the fact that Indigenous peoples do not vote as a block and certainly do not simply vote for parties on the left. Since the 2021 federal election was simply 2019 redux, there is no need to talk about it again. It is, however, important to talk about reconciliation and Indigenization, especially with regard to how they have been deployed by certain individuals for their own personal gain and not the benefit of Indigenous peoples. Justin Trudeau is a good example of one of those individuals.

Virtue signaling refers to communication of certain views and beliefs to others not because one holds them, but because they know it will make them look good. It is not a new concept; indeed, for the more Biblically minded among you, it is denounced in the Bible in the parable of the pharisee and the tax collector as well as the warning against the teachers of the law. In a certain sense reconciliation and Indigenization have become two catchwords for people who want to appear politically correct and/or show that they care about Indigenous peoples. Do not get us wrong, there are plenty of people who sincerely believe in both and make earnest efforts to rectify historic wrongs. However, because neither term is easily defined, it is easy for disingenuous individuals to make token gestures to them for their own gain with little commitment to meaningful change.

In 2015 Justin Trudeau and his Liberal Party promised a new nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous peoples; a public inquiry into missing and murder Indigenous women and girls; and an end to boil water advisories in all Indigenous communities by 2020. To date the only thing his government has followed through on was the public inquiry, although the cynic in us views most public inquiries and royal commissions as the first step government takes to do nothing at all. The federal government under Trudeau might have divided Indian Affairs into Indigenous Services Canada, Crown-Indigenous Relations, and Northern Affairs Canada—but this bureaucratic reorganization did not change how government approaches Indigenous peoples.

The government is still fighting Indigenous peoples in the courts over child welfare, numerous resource developments, and their Treaty and Aboriginal rights. In many ways, his government is not noticeably different than that of Harper when it comes to treaty negotiations or many other interactions with Indigenous peoples. And let’s not forget that he famously ejected Wilson-Raybould from his caucus in 2019 after she had the audacity to suggest that corporations, specifically SNC-Lavalin, should be subject to Canadian law without exception.

It should come as no surprise how Trudeau handled the now iconic Orange Shirt Day.

Started in 2013 by Phyllis (Jack) Webstad as a grassroots event, wearing an orange shirt slowly spread across Canada as a way to commemorate those who survived the Indian residential school system and those who never came home. One of the strengths of Orange Shirt Day was that it took place on a workday and therefore wearing an orange shirt was more than just a private moment. It was certainly not a cause for a family holiday.

In 2019, NDP MP and member of the Clearwater River Dene First Nation, Georgina Jolibois tried to create a national holiday to recognize Indigenous peoples’ experiences in Canada. Her original proposal for a separate holiday from Orange Shirt Day, which would allow it to remain a grassroots commemoration. The 2019 federal election killed this initial attempt. Rather than reintroduce the bill following the election, the Liberals let the proposal drop.

Only when the news out of Kamloops shocked the nation, and people took to the streets, did the government decide that it needed to designate a day to commemorate the legacy of residential schooling. The discovery of first hundreds then thousands of Indigenous children permitted to die over decades in government-funded, church-run residential schools forced a moment of reckoning. Echoing the earlier inquiries, in the face of widespread demands around an obvious injustice, the Liberals provided a token gesture to again show us how much they care.

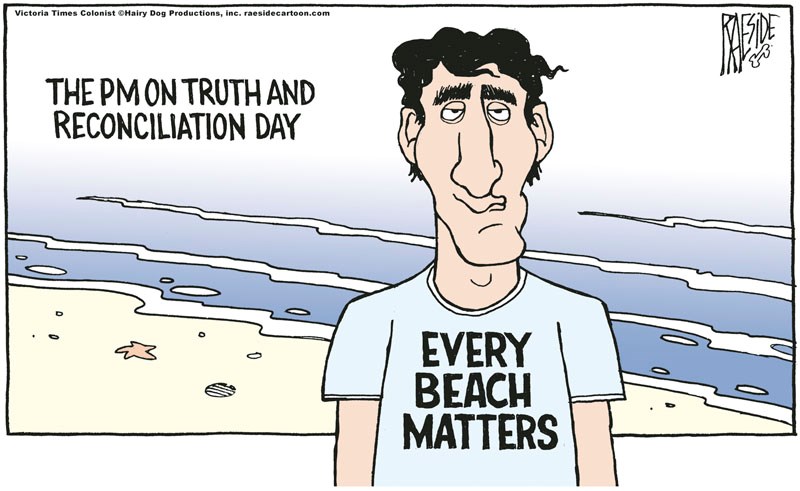

On the surface the creation of a new holiday seems like proof positive that Trudeau and his Liberals care about Indigenous peoples. There are, however, a number of tells that reveal it for the political move it is. First, it happened right before the 2021 federal election. Trudeau might not be able to bring clean water to all Indigenous communities, but at least he gave them a holiday. Second, it co-opted Orange Shirt Day. MP Jolibois had originally wanted the holiday to be 21 June, National Indigenous People’s Day. But as her private member’s bill moved through parliament the date of the holiday was moved to 30 September or Orange Shirt Day. However, the federal government did not simply make Orange Shirt Day a holiday; instead, the government transformed it, literally renaming it as National Truth and Reconciliation Day. Now as time goes by it is likely the old name will be forgotten. And all for a party whose leader decided to spend the first observance on the beach in Tofino.

Prof. Daniel Sims is the chair of the First Nations Studies department at UNBC and a member of the Tsay Keh Dene First Nation.

Tyler McCreary is an adjunct professor of the First Nations Studies at UNBC and assistant professor of Geography at Florida State University. He is author of Shared Histories.