After the discovery of 215 unmarked children’s graves in Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc on the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, the question of J. Fergus O’Grady’s legacy has come into question. The University of British Columbia is considering removing his honorary degree after an appalling letter written by O’Grady during his time as principal has resurfaced. Communities have voiced concerns over honouring a man that actively participated in such a destructive and oppressive system.

In the Nov. 18, 1948, letter, he cautions parents that “It will be [their] privilege…to have their children spend Christmas at home with [them].” One which would only be granted if very strict regulations were followed. Regulations that would have made it impossible for many families to take part in this “privilege.”

For many, this exposé has been a long time coming; for others, this is a difficult revelation.

O’Grady was nicknamed the Bulldozer Bishop. This nickname came from his desire to expand the Catholic Church’s school system. A system that forcibly separated children from their families for extended periods of time and forbade them to acknowledge their Indigenous heritage and culture or to speak their own languages. A system that has created intergenerational trauma and that continues to undermine Indigenous communities.

On June 29, 1934, Bishop O’Grady became an ordained priest of Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate at the age of 25. The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a religious order of priests and brothers that originated in France, was given responsibility for the mission of the church on the mainland of British Columbia starting in 1861.

After searching through thousands of pages of archival documents, the following information can be confirmed:

After being ordained, O’Grady found his way to St. Mary’s Indian Residential School in Mission, B.C. He served as principal here from 1936-1939.

Six weeks after his appointment, an unfavourable report was made of the school to the Department of Indian Affairs that “found fault in almost everything.” O’Grady stated his annoyance with this as it was “insinuated that the present state…was due to the change of principals,” putting the blame on his management.

It is after his short stretch in Mission that O’Grady was moved to the Kamloops Residential School, where he was the principal from 1939- 1952, during the time when it held Canada’s highest residential school population. Although it has not been determined if any of the children’s remains found on the site were put there during this time, I can confirm there were at least six recorded “pupil deaths” between the years 1945-1950 while he was principal. Records for other years could not be found.

Five of the six of these recorded deaths were blamed on disease, and one from a lack of due care and supervision signed off on by O’Grady himself. As for the other five, it is documented by staff working at Kamloops Indian Residential School that due to overcrowding, it was impossible to isolate the sick children from the healthy ones, leaving many healthy children to get sick during their time there. A letter from a grief-stricken parent also brought to attention the fact that parents were not receiving notice of their children being sick before it was too late. In this case, the children’s parents were only notified by telephone the morning of the day the child died. Although they came right away, the child passed before they were able to get there.

In fact, primary documents reveal that there were serious concerns over the fact that the school was overcrowded and over-capacity.

After twelve years in Kamloops, O’Grady became principal of the Cariboo Indian Residential School until 1953. After which, he was named as “Provincial in charge of all English-speaking Oblate priests in Canada” and was ordained Bishop and appointed Vicar Apostolic of Prince Rupert by Pope Pius XII on March 7, 1956, and set about establishing Catholic day schools for an “integrated” student body.

Although O’Grady was no longer principal of any of these schools, as the highest-ranking official in the region, he continued to preside over residential schools that children were forced to attend and where they continued to receive verbal and physical abuse.

An excerpt from the Prince George Diocese states that “With only four Catholic schools in the nearly 347,000 square kilometers of northern BC, it was clear to Bishop O’Grady from the start that Catholic education was a primary need. He began a recruitment drive and hundreds of young people from around the world, inspired by his vision and enthusiasm, began arriving to help. In four years, the number of schools increased to thirteen… Over the next 35 years approximately 4,000 people from five continents became part of this movement known as the Frontier Apostolate.”

In 1960, O’Grady opened the first known integrated school in the region, known as the Prince George College. In the 2001 thesis written by Kevin Beliveau, a former student and a Catholic teacher, it is stated that after reading through O’Grady’s personal files, “what is clear is that the ‘integration’ attempted at Prince George College was not the policy envisioned by government or Indian Brotherhood policy-makers who saw a synthesis of cultures -rather than varieties of tokenism and outright assimilation.”

He also writes, “The school lay on a foundation of a carefully constructed ethos, the sacrifices of hundreds of lay volunteers, and the involuntary financial subsidies provided by Aboriginal students from approximately 1960 to 1989." The school received government subsidies for every Indigenous child enrolled, and after government subsidies for Indigenous students ended, recruitment of these children steadily decreased. The school shut down for good in 2001.

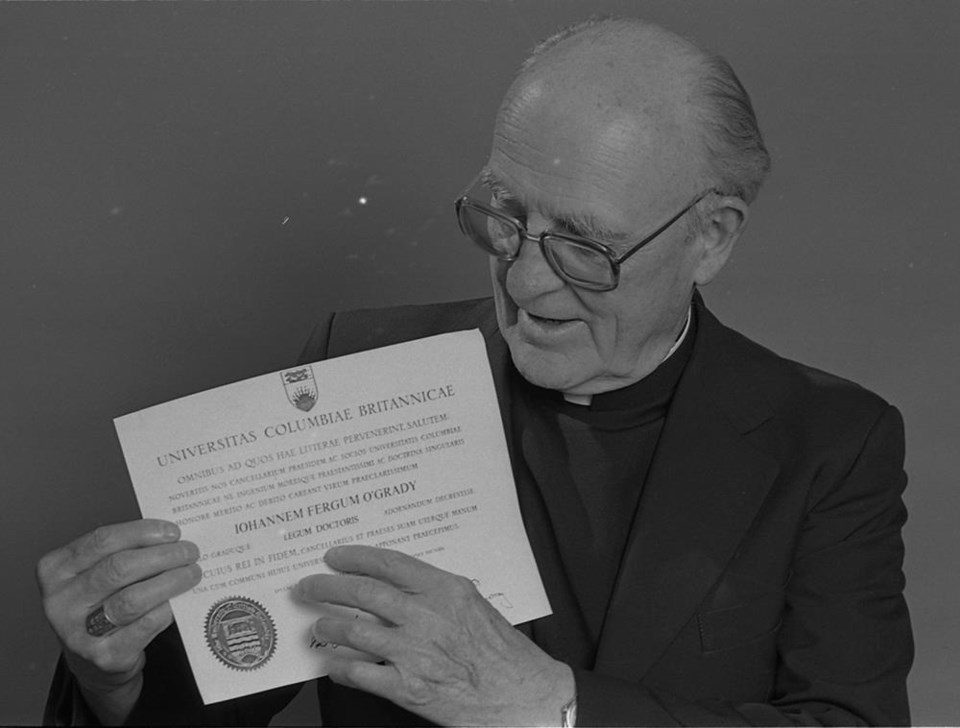

In 1986, O’Grady retired and was awarded the honorary “doctor of laws” degree conferred to him from UBC for his religious work with “Native Indians”. But as Beliveau notes, “His missionary mindset was predicated on the assumption of European spiritual and cultural superiority.”

During his contentious career, O’Grady headed three different residential schools (all of which have documented physical and verbal abuse), and as the Bishop of the Prince George Diocese, O'Grady continued to supervise over residential schools where children continued to receive verbal and physical abuse.

O'Grady was succeeded as Bishop of Prince George by Hubert Patrick O'Connor. O’Connor resigned in 1991 after being charged with sexual assault in the 1960s during his time as Principal of the Cariboo Residential School. He was convicted in 1996 for rape and sexual assault against two victims. As the highest-ranking Catholic official in Canadian History to be charged with sex crimes, “The case attracted widespread attention, as it became a symbol for debate about the role of the justice system in handling cases of aboriginals abused at church-run residential schools.”

After his retirement in 1986, O’Grady remarked that he had relatively few disappointments or regrets during his career. After listing those few disappointments, none of them included the untimely deaths of pupils during his time in Kamloops or the alleged cases of physical and sexual abuse of students he presided over. This includes students who were still under his care during O’Connor’s time at the Cariboo Residential School. Ironically, the “untimely deaths” of three other priests were at the top of his list of regrets.

- Alyssa Leier is the curator at The Exploration Place.