They called him the King but Arnold Palmer should have been called the trailblazer, the lightbringer, the groundbreaker, the "show me the money" man.

The legendary golfer died Sunday at the age of 87. His effect on golf was as profound as Wayne Gretzky's effect on hockey in America after being traded from the Edmonton Oilers to the Los Angeles Kings. Muhammad Ali may have been The Greatest but even Ali didn't change the business of sports the way Palmer did.

Every professional and elite amateur athlete today that signs an endorsement deal has Palmer to thank. He was the first client of Mark McCormack at International Management Group, who put Palmer's face and name on everything from motor oil to the ubiquitous line of men's clothing found in a department store near you. IMG made Palmer incredibly rich and Palmer helped make IMG into a global talent agency, representing clients in sports and entertainment eager to cash in on their fame.

Palmer didn't crack $2 million in career earnings actually playing golf but, as the Associated Press obituary story on Palmer pointed out, he was the third highest-earning golfer in 2011, raking in $36 million nearly four decades after he last won an event on the PGA Tour. In other words, Palmer made far more money being Arnold Palmer than he did sinking birdies.

Palmer was loved, both by golf fans and by companies eager to work with him to promote their products, for his easy demeanour off the course, his hard-charging showboating on the course and that handsome masculinity topped off with his confident grin. He took a game reserved for elite snobs and made it mainstream. Before Palmer, nobody referred to golfers as athletes, nobody spent a perfectly good Sunday afternoon watching the final round of a golf tournament on TV and nobody called golf a sport, never mind a physical game.

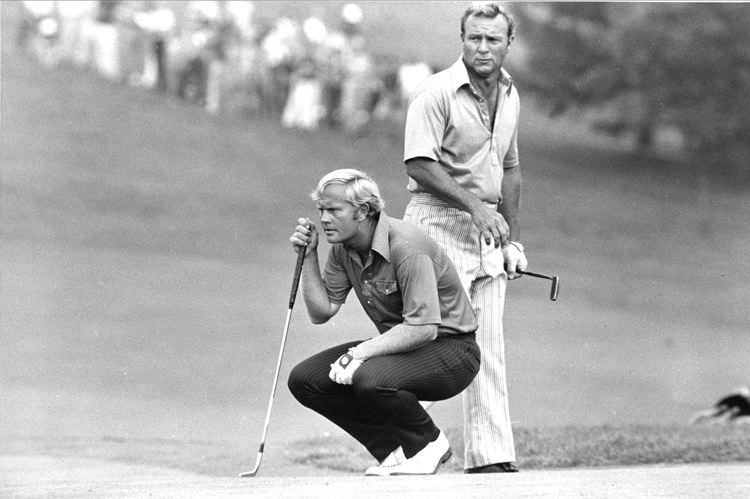

He wasn't even the best golfer of his generation.

That title belongs to Jack Nicklaus, who remains the best golfer ever if best is measured by number of major tournaments won. Gary Player was also better than Palmer, again if majors and tour wins are the yard stick.

Yet Palmer was adored and his fan base was known as "Arnie's Army." As America came into its own in the mid 1950s, it was Palmer, not Gordie Howe or Mickey Mantle or Bill Russell or Johnny Unitas, who reflected the mood of the country in that post-war decade. Cam Cole pointed out in his Postmedia column that Palmer was that rare combination of a man who men wanted to be and women wanted to be with.

A generation of baby boomer children grew up watching him hitch up his pants and hammer the ball with authority on TV, and then became golfers and fans of the game. If they couldn't be him, they could at least dress like him and head out to the course wearing clothes with his name, hitting Arnold Palmer balls off an Arnold Palmer tee with an Arnold Palmer club.

Previous generations fell in love with their athletes through the newspapers and the radio. Palmer was the right man at the right time for television and for the baby boomers, setting the stage not just for golf but for every major sport that developed through television and made its elite players into household names.

The glossy sheen to major sporting events and to the top players started with Palmer.

IMG - the company that started with Palmer - is the agency behind the marketing of the World Cup of Hockey and the entire National Hockey League. Alexander Ovechkin was their first NHL client.

As Palmer aged, he embraced his role as golf legend and ambassador, teeing off each year at the Masters and taking part in various events to promote the game with a new generation of players young enough to be his great grandchildren.

From all accounts, he was never comfortable being called The King, likely because it evoked Elvis Presley and also because he never saw himself as above any of the other players on the professional tour nor above any of the fans he would tirelessly sign autographs for at the major championships. A commoner king, then adored by all, but perhaps best remembered as a pioneer who helped turn popular sports into corporate empires and individual athletes into savvy promoters and business leaders.

-- Managing editor Neil Godbout