In the wake of my last column about backyard chickens in Prince George, I’ve noticed quite a contradiction.

Why are backyard chickens illegal in Prince George while people have free rein to spray their properties with toxic pesticides?

It seems that most readers agree it’s acceptable for the government to deny us the freedom to raise chickens on our own private property. But if government were ever to restrict the right to spray lawns with carcinogenic pesticides, all hell would break loose.

There is, however, a clear distinction to be made.

The nuisance factor from backyard chickens is minimal — as long as there are no roosters. Some people think chickens attract pests, but the opposite is true.

Chickens are excellent at pest control, consuming mice, slugs, ants and other garden nuisances.

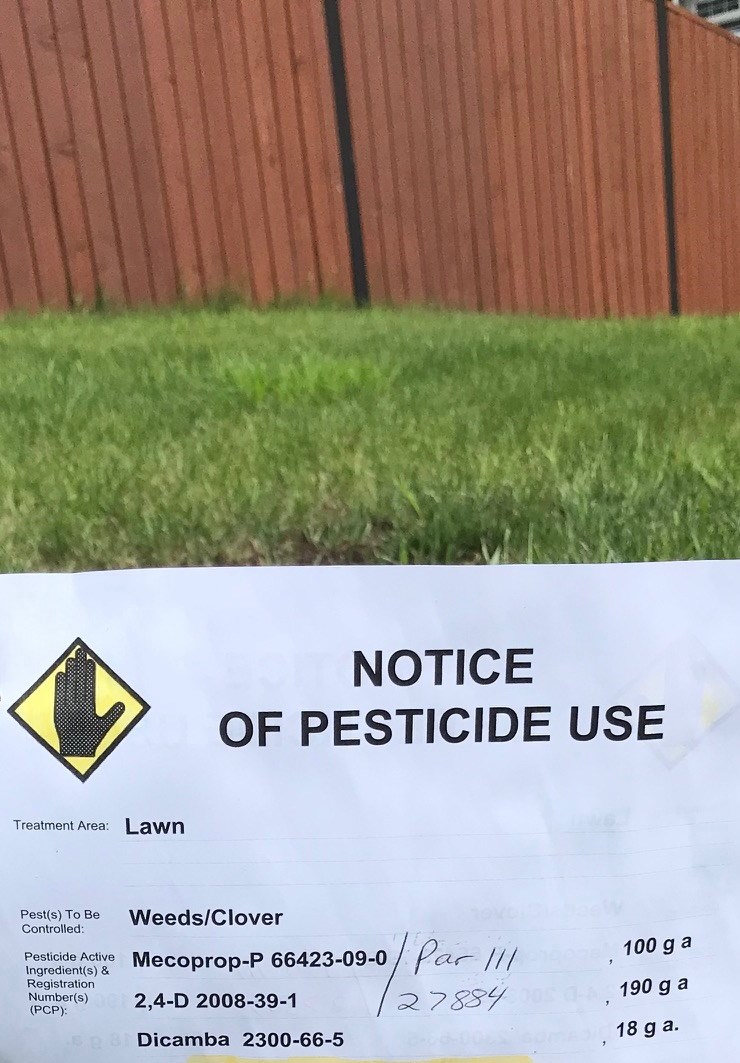

Meanwhile, when people spray their lawns with Killex, glyphosate or one of the pyridine herbicides, they’re not just exposing themselves to chemicals that have been linked to cancers — potentially placing a burden on the public health-care system — they’re also contributing to a wider problem.

Contaminated lawn clippings, often disposed of as “green waste,” end up in the public compost stream.

As far back as 20 years ago, researchers at the University of Guelph found that the three active ingredients in the commonly used Killex — dicamba, mecoprop and 2,4-D — didn’t break down as quickly as the grass in compost piles. After 10 weeks, the concentration of these chemicals, as a proportion of the remaining material, actually increased.

Good luck growing vegetables in that.

Contaminated green waste is a major problem. Herbicide carryover in compost and manure is a well-documented cause of plant health problems for years afterward. It can render a garden sterile — particularly when it involves persistent pyridine herbicides. These chemicals — including Milestone, Grazon and Millennium Ultra — kill broadleaf plants but not grasses, making them common on lawns, golf courses, cemeteries, hayfields and even in public forests.

These herbicides are absorbed into grass and hay and can be passed on through manure from animals fed with contaminated feed. If you buy Grazon-treated hay, your resulting manure will also be contaminated and should not be used to grow vegetables.

When purchasing hay, you can at least ask the grower whether herbicides were used — especially pyridine-based ones. Unfortunately, if you’re picking up municipal compost for your garden beds, that’s impossible. As far as I know, pesticide contamination is not being tested.

But even if your clippings never leave your property, your pesticides don’t stay put.

Dicamba, one of the key ingredients in Killex, is notorious for volatilizing and drifting off-target, potentially damaging or killing neighbouring trees and shrubs.

This has happened both in residential areas and on a landscape scale across the American Midwest.

Pesticides also leach into watersheds, wildlife and even well water. And don’t rely too heavily on Health Canada’s reassurances — their track record on pesticide safety is showing up everywhere.

A federal court recently ordered the agency to reassess glyphosate products, and a National Observer investigation revealed it colluded with a pesticide maker to ensure a dangerous product stayed on the market.

Apparently, the government has no authority to stop you from poisoning the public commons — the soil, the water, the shared environment. After all, whatever burden that places on cancer wards is surely offset by the increase in civic real estate values, thanks to those dreary, lifeless green lawns of modern chemical science.

At the end of the day, we find ourselves in a society where superficial symbols of vanity are more important than staying connected to the natural world.

And that’s why it’s legal to use dangerous pesticides on your personal property in downtown Prince George — but not to keep harmless backyard chickens.

James Steidle is a Prince George writer.