You are walking down the street and the person in front of you, perhaps 30 metres ahead, coughs. Unbeknownst to you, they are infected with SARS-CoV-2, and their cough expels tiny droplets containing the coronavirus. The droplets waft back on the breeze and you inhale one.

Will you get COVID-19?

What if you inhale a million droplets?

Can we detect them?

How do we know if the virus is around us?

First, don’t panic.

If it were that easy to get infected from people coughing down the street, we would all have COVID-19 by now. It is easy to spread by virus standards, but not that easy.

In my previous columns, I discussed what it means for coronavirus to be an RNA virus, and what the parts of a virus are and what they do. Today, I am going to talk about how we detect coronavirus.

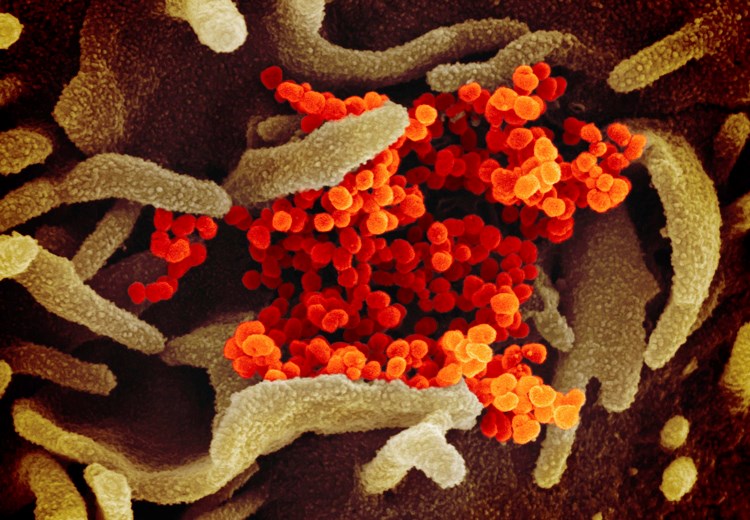

The virus in liquid droplets that can infect new hosts is quite simple. It has an RNA genome (the instructions for making more viruses) and a capsid (or shell) made of proteins. It also has a membrane made of lipids (fat) that help to protect it from the environment.

The lipids aren’t useful to detect, because they come from the host cell in which the virus was made, so if you took a throat swab and looked for lipids you would find them. But you wouldn’t know if they were from your cells or from a virus.

The RNA, however, is unique to the virus. An easy way to detect the virus is therefore to use the polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, to make lots of DNA copies of a small part of the viral genome (in a test tube, RNA can be copied into DNA and vice versa). Using a dye that sticks to DNA, the PCR reaction becomes fluorescent if these copies are made. The fluorescent signal is easily detected.

If there was no coronavirus to start with, then there is nothing for the PCR reaction to copy, so no fluorescent signal.

And if there are many viruses, the signal becomes detectable sooner than if there are few.

In principle, the PCR reaction is sensitive enough to detect a single virus. So we could go around swabbing door-handles, park benches and drinking fountains to see where the virus is.

There are three reasons not to do that: first, the virus does not last very long when it is outside of a host, so by the time we knew that a door-handle was contaminated the virus would probably no longer be active anyway; second, it is much easier just to remove the virus with cleaning wipes or soap and water; and third, the PCR test is needed in hospitals and we do not have the capacity to monitor our environment in a useful way.

The other part of SARS-CoV-2 we can detect is the protein shell.

Unfortunately, to detect a protein we need an antibody to it. Everybody who has been sick with COVID-19 has antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 proteins, and scientists around the world have been working night and day to figure out which of the billions of antibodies in the patients are the ones that stick to coronavirus proteins. Then they have to make those antibodies in the lab and turn them into a test that is as easy to use as a PCR reaction.

That is why the PCR test came first - it is so much easier to do. And it is much more sensitive.

The antibody test is ultimately more useful, however. Why? Because once you have gotten over your infection, there are no more viral RNAs to detect. The PCR test will show nothing. But your body will keep making antibodies against the virus for months or years.

With an antibody test, we can tell who has been exposed and is therefore hopefully immune. All the immune people may be able to go back to work and resume their lives without risk of catching SARS-CoV-2 again.

If we are lucky.

If we are unlucky, the immunity may not last, and COVID will become like the seasonal flu.

So how many viruses do you have to inhale to get sick?

We don’t yet know, but there is some evidence that exposure to more viruses results in a worse case of COVID-19. This would make sense, as more of your cells would have viruses copying themselves and infecting other cells, so your immune system would have less time to mount a defence. If a single virus infects you, your body may well detect the infection and kill the infected cells before the virus can spread.

Scientists are already trying out antibody tests. Soon, they will be cheap and abundant, and we will easily figure out who has already been exposed to coronavirus. They won’t be sensitive enough to detect viruses in our environment, however, so as long as the virus is circulating we must be conscientious about washing our hands and wiping surfaces that others may have touched.

‑Stephen Rader is a professor of biochemistry at the University of Northern British Columbia. His laboratory studies how RNA is processed by our cells. He is the founder of the Western Canada RNA Conference.