Q: Why do some crescents in Prince George have even- and odd-numbered houses on the same side of the street? Shouldn't they be all even on one side, and all odd on the other?

A: A quick search of the city's online mapping software turned up at least three examples of this phenomenon (see photos) although many others likely exist:

3254 St. Frances Cres. is directly next to 3395 St. Frances Cres.

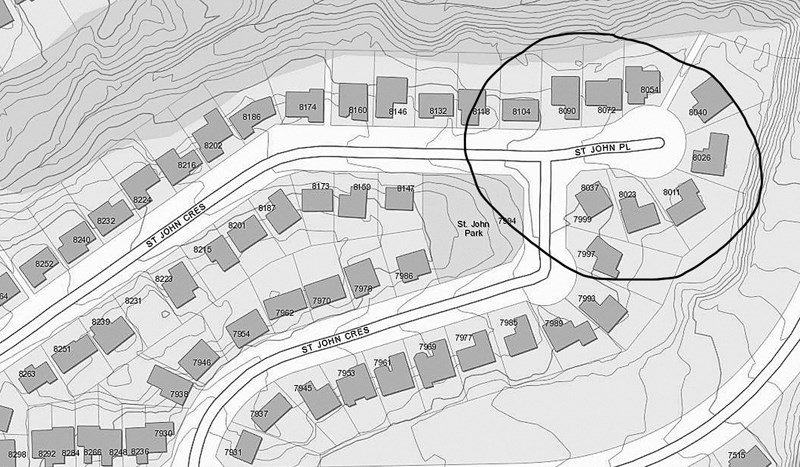

On St. John Crescent even addresses 8104 to 8316 are on the same side of the street as odd addresses 7931 to 7999.

Otter Crescent houses 655, 671 and 695 are on the same side of the street as all the even addresses on the street.

These seemingly-irrational number schemes are a frustration for people unfamiliar with the street. After all, building numbers were invented to make it easier to find unfamiliar addresses and reduce confusion.

According to an article by Anton Tantner, published in 2009 in the French social science journal Histoire & Mesure, houses and buildings were largely identified with a name and sign - rather than a number - until street numbering was introduced in Europe in the 18th Century and spread to Europe's colonies.

Relying on street and building names led to duplication and confusion.

The first house numbers in London appeared on Prescot Street in 1708 and, by 1768, 75 per cent of houses listed in a published street directory of the English capitol had street numbers.

However, just because street numbering had been introduced did not mean street numbers looked the way they do today. According to Tantner, some examples of early systems used include:

In 1737, Prussia ordered villages to put a unique number on every house in a village before the army arrived, to make it easier to billet soldiers. By 1792 Prussia had expanded the system to include all the territory under it's control to make billeting and conscripting soldiers easier.

In 1750-51 Madrid introduced street numbering. Houses were organized into numbered groups called manzana, with every house in the manzana numbered in consecutive order. To find an address required knowing the name of the street, the number of the manzana and the individual house number within the manzana.

The German city of Mainz began street numbering in 1771. The city was divided into six sections, each was assigned a letter from A through F, and then the houses in the section were numbered consecutively from a single starting point.

When new buildings were constructed, fractional addresses were introduced so addresses like D 183 1/4 existed.

In 1779 Marin Kreenfelt de Storcks, editor of the Almanach de Paris, wanted to make his Paris city directory more useful. He and his assistants started going out at night painting numbers on the main entrances of buildings in Paris -which previously had no unified system of numbering - by starting at one side of the street and numbering each building in order. They would then cross the street and continue up the other side, so the highest-numbered building on the street would be directly across from No. 1. In 1799 Berlin also adopted this horseshoe method of numbering, which was also used widely in England and elsewhere.

Modern street numbering in Canada and the U.S. - and much of the world - is based on two systems: the so-called French system and the Philadelphia system.

The French system - also called the odd/even system or orientation numbering - was introduced in Paris in 1805 under the rule of Emperor Napolon Bonaparte (although new historical evidence suggests it may have been introduced to France from the United States, Tantner wrote). Numbers start at one end of the street with even numbers on one side and odd on the other, rising in consecutive order.

This system made it easier to orient oneself on the street, compared to the older horseshoe method.

In addition, because the street number is an arbitrary number assigned as an address, it became easier to assign numbers to empty lots for future developments and skip numbers to allow lots to be subdivided without having to resort to cumbersome fractional addresses, adding letters (223A, 223B, etc.) to street addresses, or overhauling the whole numbering system periodically.

In much of Prince George, street numbers increase by eight for every average-size lot -potentially allowing lots to be subdivided many times without ruining the number scheme.

The Philadelphia system, introduced in Philadelphia in 1856, took advantage of the numbered grid-style streets and avenues being built in new cities in North America to improve on the French system.

Under the system, only the last two digits of the address numbers vary on each city block. The hundreds-place numbers indicates the block's location on the numbered street grid.

For example, the Citizen's office is at 150 Brunswick St. is on Brunswick Street midway between First Avenue and Second Avenue, 440 Brunswick St. is between Fourth Avenue and Fifth Avenue and 770 Brunswick St. is between Seventh Avenue and Eighth Avenue.

Even though Prince George's downtown streets are named instead of numbered, the same principle applies to addresses on the avenues.

All the addresses on avenues downtown between Brunswick Street and Quebec Street start with 13 followed by two more digits. The addresses between Brunswick Street and Victoria Street all start with 14.

In effect, Quebec Street is 13th Street, Brunswick Street is 14th Street and Victoria Street is 15th Street for the purpose of the numbering grid.

The Philadelphia system can be seen in parts of the bowl where there are numbered avenues.

So, with street numbering well developed by the mid-19th Century, what is going on with the crescents in Prince George?

According to Ian Wells, city director of planning and development, the City of Prince George has never had a street numbering bylaw. Street numbers are determined by an internal policy used by city staff when new streets are developed.

In the past, under that policy, street numbers on crescent streets were odd on the south and west sides of the street, and even on the north and east sides of the street.

So in the Otter Crescent example, 655, 671 and 695 are on the south side of the street and thus have odd numbers, while the rest of that side of the street are east and north and have even numbers.

The same thing is happening in the St. Frances Crescent example. As the street turns, the houses on the inside of the crescent are either on the north or south side, and thus have even or odd numbers.

However, in the St. John Crescent/St. John Place example, there is something different going on. Wells said the city's old policy said that street numbers on cul du sacs should be even on one side and odd on the other.

When the street numbers reach the end of St. John Place, they switch from even to odd. In order to keep the numbering consistent, the switch was carried over back to the crescent. That is why 7993 and 7997 St. John Crescent - which are on the east side of the street and should have had even numbers under the old numbering policy -have odd numbers.

"That wouldn't be the case now, it would be consistent," Wells said. "The new standard is even/odd to be standard on one side of the street."

In the case of new cul du sacs, the street numbers are either all even or all odd, he added.

Wells couldn't say when the city's policy changed, but did say his staff plan to propose the city's first street numbering bylaw to city council sometime in 2015 to clarify the city's rules for street numbers.

Hopefully it will save future generations of pizza delivery drivers headaches trying to find addresses that are on the wrong side of the street.

Do you have questions about events in the news? Are you puzzled by some local oddity? Does something you've seen, heard or read just not make sense? Email your questions to [email protected], and award-winning investigative reporter Arthur Williams will try to get to the bottom of it.