This week in Prince George history, Sept. 18-24:

Sept. 24, 1920: Journalist Russell R. Walker reflected on the changes 10 years, the Spanish Flu epidemic and the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway had brought to the region west of Prince George.

"Since his recent visit to this district, which coincided with the visit of Premier Oliver and Minister of Lands Pattullo, Russell R. Walker has (been) writing about the country along the GTP," The Citizen reported.

Walker had served as a representative of the North Coast Land Company in the Prince George area for many years before taking up journalism. He wrote an account, published in The Citizen, comparing what he saw in the Fort Fraser area in 1920 to when he first ventured through the region in 1910.

"Ten years ago Fort Fraser was an oasis in a wilderness, the only place where supplies could be purchased for miles around. Its factor was a man of power, its trade extensive," Walker wrote. "At that time the Indian trade was a flourishing one and every autumn the Indian villages for fifty miles were depopulated and Fort Fraser became the rendezvous. For the salmon from the distant Fraser (River) literally swarmed up the Nautley (River) and native men, women and children preyed upon them, catching and curing countless thousands for winter food.

"A fishing season at Fort Fraser was a sight worth seeing. Few white men visited the district. An occasional lineman on the government telegraph trail passed through and stopped over night, or a wandering survey party camped nearby. New Indian towns sprang up over night and the river was alive with canoes," Walker continued. "Silent red men speared salmon as they struggled up through the riffles, boys pulled the helpless fish from the traps, and the squaws never ceased their busy chatter as row after row of fish was hung up to dry."

In September 1910 Walker had hiked through the region, following the telegraph trail on his way to the coast. When he reached the Nechako River, he purchased a dugout canoe from a local aboriginal man for $10 and poled up river for 20 miles.

"The river was literally teeming with salmon. Some flashed by with strength unimpaired, others struggled feebly against the slight current, while many floated belly up, still wriggling feebly in a determined, but hopeless, effort to reach the desired spawning grounds," Walker wrote. "I have seen fish on the Upper Nechaco still fighting valiantly towards the goal when their flesh was decayed and a blow from the canoe paddle would shatter them."

But 10 years later the situation had changed entirely, Walker wrote.

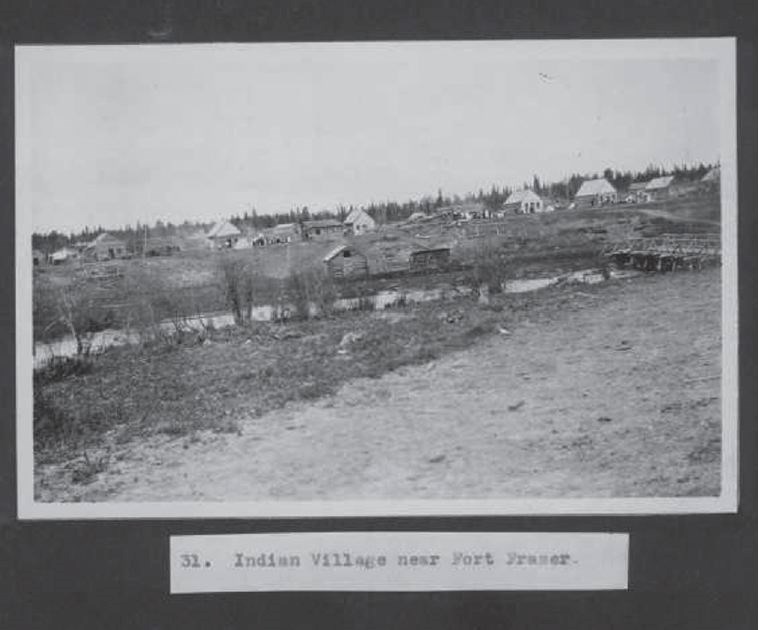

"The closing chapters of the lives of both the Indians and salmon are being written. The Indian village on the Nautley has few tenants, the river few salmon," Walker wrote. "The dread 'flu' removed many of the natives, and white settlers have taken their places. The forest is disappearing rapidly in many sections, the steel highway has taken the place of the riverway, and trappers' cabins have given way to settlers' homes."

Agriculture was starting to take root in the region, with new farmland in the Marten Lake area selling for $4 to $8 an acre.

"Settlers in this district are going in chiefly for mixed farming. Fodder crops are given most consideration and dairying promises to become the chief source of revenue," Walker wrote, adding a prediction that the region would soon be famous for its dairy products.

"Stuart Lake yields the biggest fish caught in that section of the province. Indian legend says that the mightiest fish of all the northern lakes meet here annually in mortal combat, and since only the strongest of the piscatorial gladiators survive, the fish caught here are exceptionally big," Walker wrote. "Whatever the reason, certain it is that Stuart Lake cannot be excelled as a fishing ground."

While some efforts were being made to commercialize the fishing on Stuart Lake, Walker said he hoped they would not succeed as the lake has greater promise as a tourist area.

"Another unusual feature of the Stuart Lake country, and one which practically assures its commercial future, is the unique system of navigable waterways found there," he wrote. "Stuart River, which joins the Nechaco opposite the GTP station of Stuart, is approximately 60 miles long. With the exception of the lower twelve miles of its course, it is navigable for five to six months of the year for small steamers, boats with a capacity of twenty-five tons or more."

Walker's firsthand account illustrates the triple tragedies which befell the Nadleh Whut'en, Nak'azdli and Stellat'en people in the Fort Fraser area between 1914 and 1919: disease, famine and colonization. Read on for more:

The deadly Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918-19 killed an estimated 20 million to 40 million people worldwide, according to a report by Stanford University researcher Molly Billings. The Government of Canada estimates 50,000 Canadians were among the victims.

For the indigenous people of the Fort Fraser area, it would have come at the same time as a dramatic crash in the sockeye salmon run - a critical traditional source of food.

According to a report by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, a rockslide near Hell's Gate blocked the cross-section of the Fraser River in 1913-14. Very few sockeye passed the barrier to spawn successfully in the upper Fraser River and tributaries like the Stuart River until blasting and the construction of fish channels reopened the river.

The result was a collapse of sockeye runs starting in 1917. The catch of sockeye in B.C. went from 10-12 million per year in early 1900s to four to five million per year following the landslide, with much of the losses focused in the upper Fraser system.

B.C.'s sockeye population took decades to recover, not reaching previous normal levels until the 1970s.

The ceremonial last spike of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, connecting Prince Rupert to Edmonton, Winnipeg and beyond, was driven in Fort Fraser on April 7, 1914. The following influx of settlers, industry and land developers was the metaphorical last spike in the traditional way of life for the local First Nations people.

Construction of the infamous Lejac Residential School, located between Fraser Lake and Fort Fraser, was completed on Jan. 17, 1922 -working to nearly destroy the transmission of traditional language and culture from generation to generation.

The story of the Carrier peoples from the region is a grim reminder of how quickly a combination of natural and human factors can change, completely upending people's way of life.

To explore 100 years of local history yourself, visit the Prince George Citizen archives online at: pgc.cc/PGCarchive. The Prince George Citizen online archives are maintained by the Prince George Public Library.