This week in Prince George history, March 25-31:

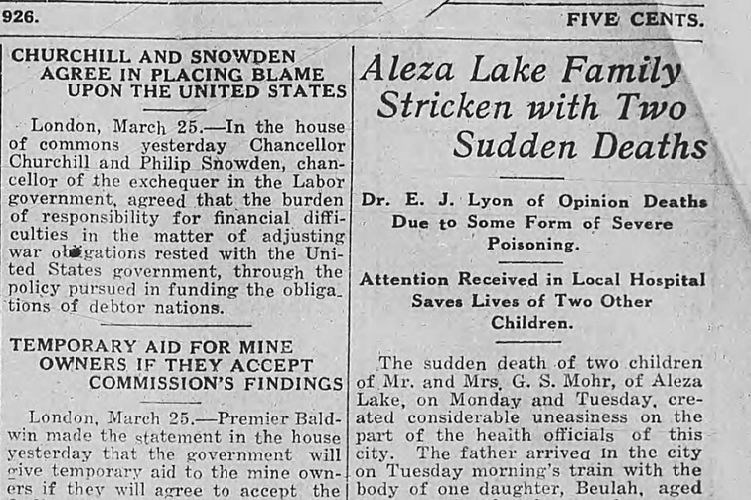

March 25, 1926: An Aleza Lake family was mourning the sudden and mysterious deaths of two young daughters, The Citizen reported.

"The sudden death of two children of Mr. and Mrs. G.S. Mohr, of Aleza Lake, on Monday and Tuesday (March 22-23), created considerable uneasiness on the part of the health officials in this city," The Citizen reported. "The father arrived in the city on Tuesday morning's train with the body of one daughter, (Berri), aged five, and shortly after word was received that a young daughter, (Vida), aged two, had died suddenly in the family home."

Mrs. Mohr arrived on a local train Tuesday afternoon, with Vida's body, and their two other children – an infant and a four-year-old daughter named Freda.

"The two other children were rushed to the hospital. The infant was shortly discharged, but for a time the life of the child Freda was in imminent danger," The Citizen reported. "She was out of danger this morning and her recovery is considered a matter of a few days. Dr. E.J. Lyon, who had charge of the children in the hospital, is of the opinion the children suffered from a strong form of poisoning, the exact nature of which will not be disclosed until an analysis can be made of portions of the organs of the deceased child, (Vida)."

Mrs. Andrew Young, who had helped take care of the children, showed signs of the same symptoms, raising concerns of some type of disease outbreak. However, after being admitted to the hospital it was shown she "had no temperature and was suffering from nervousness and strain more than anything."

"G.S. Mohr, the father of the victims, is very much shaken over the calamity which has overtaken his family," The Citizen reported. "He says the children were playing about the house on Sunday morning, apparently in the best of health, some of them amusing themselves at drawing with crayon pencils."

Then around noon Berri began to complain of stomach pain, but it wasn't until about 2 a.m. the following morning that her condition was considered serious enough to send a messenger to summon Dr. Laishley from Giscome.

"The doctor responded to the call as quickly as possible, but the child died at 8:30 on Monday morning, or within (20) hours of the first complaint of illness," The Citizen reported.

When Mohr left for Prince George to bring Berri's body for burial, the other children were in good health, but Freda started feeling ill shortly after he left on the train.

"Mrs. Mohr then decided to bring Freda to Prince George on the local train, but before the train arrived (Vida)... was stricken with the complaint and died before she could be put on the train."

An inquest was opened into the girls' deaths by Coroner Harry Guest, but it was adjourned until Dr. Lyon could perform an autopsy.

It's hard to imagine what it would be like to have two of your children die suddenly and mysteriously in the course of two days, and have another hospitalized on the brink of death.

The original Citizen story was inconsistent with the names of the girls. Vida was called Vida May or Ida May, and Berri was called Buelah or Buell.

The Prince George Cemetery records show that Berri Roberta Mohr and Vida June Mohr were interred there on March 23 and March 25, 1926. For clarity I've used the girls' names as recorded on their gravestones.

Dr. Lyon did conduct his autopsy, and the coroner's inquest reconvened on May 4, 1926 to examine the cause of the sudden deaths:

"Dr. E.J. Lyon, who attended the child (Vida), gave it as his opinion the child was suffering from ptomaine poisoning. The stomach, with its contents, as well as the other organs of the body of the deceased (Vida) were sent to Vancouver for analysis, but the report was to the effect no trace of poison could be discovered," The Citizen reported. "An analysis of the crayons, with which the children had been playing before they were taken ill, was also made and no trace of poison was found in them."

Lyon testified before the jury of the coroner's inquest explaining why he believed ptomaine poisoning was to blame, and why traces of the poison might not have been discovered.

The jury of the coroner's inquest ruled the deaths were "probably due to poisoning."

You don't hear about ptomaine poisoning anymore. Ptomaines are a group of foul smelling and tasting compounds found in decomposing food.

In the past they were believed to be the cause of food poisoning, but science later proved that the substances can be harmlessly digested. What makes eating spoiled food dangerous is the potential presence of poison-producing bacteria like Clostridium botulinum – the bacteria which causes botulism.

There is no way to know now if Dr. Lyon was (almost) right and the girls died of an acute case of food poisoning, or if their sudden and tragic deaths were the result of some other cause.

To explore 100 years of local history yourself, visit the Prince George Citizen archives online at: pgc.cc/PGCarchive. The Prince George Citizen online archives are maintained by the Prince George Public Library.