I have needed some time to articulate exactly what I felt was appropriate to say and how I could honour my thoughts around what recently happened.

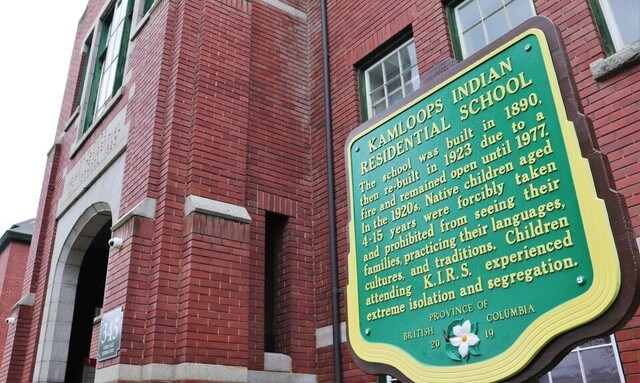

This past week it came to light that the bodies of 215 Aboriginal children were found buried at a former B.C. residential school. All of them undocumented deaths. At first, I couldn’t even comprehend the totality and horror of the situation. Because although it has always been inherently part of my culture and upbringing, it always seemed relevant yet distant.

To imagine that not only is this still an active part of who we are but the very real families that who are only now allowed to begin a new stage of grieving. I am the first generation in my family that has not been subjected to residential schools. But the impacts have still been felt. We live in a time of so-called upheaval and change where human rights are at the forefront. Still, I don’t connect to the word’s reconciliation or culpability.

It spurred me to do some digging into how not only the emotional aspects are still felt but what are the lasting “tangible” impacts. It is estimated more than 150,000 children attended residential schools in Canada from the 1830s until the last school closed in 1996. The NCTR estimates about 4,100 children died at the schools, based on death records, but has said the true total is likely much higher.

In an article regarding addictions, Aboriginals seeking help were as high as 17 per cent compared to the Canadian average of eight per cent. The provincial rate of children in care with the Ministry of Children and Family services as of 2019 was 6,263 with 4,111 of those being identified as Aboriginal. Although Aboriginal people are only 5.9 per cent of the adult population of British Columbia, they are 29.7 per cent of the adult population in correctional centres and 25.8 per cent of people under community supervision. Graduation rates for Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Students as of the 17-18 school year showed a gap of 16.9 per cent. And according to Stats Canada, only 58.6 per cent of First Nations people between the ages of 25 and 54 years lived in a household that was defined as food secure.

Now these statistics were found on a very surface Google search and obviously outdated, but this was what I could find at a glance. So what do these numbers mean in the grand scheme of things? We need change. The change and healing that we are so desperately seeking still eludes us.

What limited resources I have come across have done nothing to aid in my journey to recovery. Intergenerational trauma is a very real thing. So real that studies have shown it’s altered our DNA. This isn’t an issue of Aboriginals alone. This is an issue of community and government. Because, believe it or not, society is only as strong as its most vulnerable members.

Education, compassion, unity. These are the core building blocks of eliciting change. So, before you think that this isn’t your problem, I implore you to examine your humanity closer and redefine what it means to be a member of our society.

Laura Mueller

Prince George