The Prince George timber supply area, which represents the largest in the province, is facing a drastic drop in its logging options.

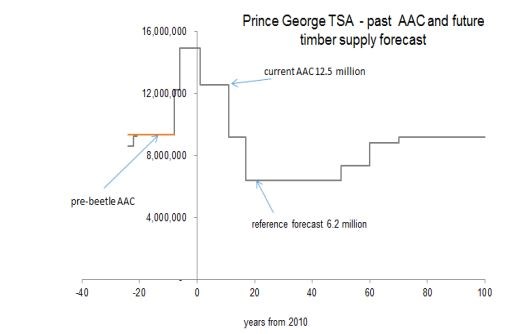

A forecast shows the annual allowable cut diving from the current 12.5 million cubic metres available since 2011 to an expected 6.2 million cubic metres in 2020. Before the mountain pine beetle epidemic, it sat at 9.2 million.

Looking at those numbers Coun. Albert Koehler said there's cause for concern.

"I think the public is not really aware what's happening there because that's the loss of wood more than 50 per cent that's coming our way, correct?" said Koehler after the Monday presentation to council from the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations.

"It's a significant reduction and a significant reduction in economic activity that we can anticipate," said John Pousette, team lead in the Omineca Region.

"That's what I'm getting to. We'll suffer," replied Koehler. "The future is not so rosy if we look towards 2020 because nobody knows what's happening."

Prince George is in the midst of its fifth review ahead of the chief forester's decision for the Annual Allowable Cut (AAC), expected to be released in the fall. B.C. last completed a review in 2010, when it decided to reduce the cut to 12.5 million cubic metres from its peak of 14.9 million cubic metres.

More than three quarters of the current cut available to licensees must be using the dead pine.

As the area's available forest drops, the value of logging pine beetle - a focus of the province since 2011 - is similarly fraught. But Pousette reported data that shows the shelf life of the dead pine has become an area of "significant concern."

At the last timber review, it suggested that after 15 years the dead pine will be no longer useful.

New data shows that at 15 years, only 40 per cent of the volume can be used. At 10 years, it's about 60 per cent.

"The amount of merchantable timber you can get off those blocks just declines over time," explained Pousette.

Occupying the northern central interior of B.C., Prince George's timber supply area (TSA) stretches west to Vanderhoof and north to Fort St. James and east near the Alberta border, representing 17 per cent of the province's total wood supply - or 7.97 million hectares.

Pousette explained that the supply area is still harvesting natural forests and doesn't use any second growth for its supply. The amount of available trees in the 40 to 70 year range is of particular concern.

"We have an age-class imbalance here and it's going to cause us some problems later," Pousette said.

What Prince George is experiencing is part of a much larger supply fall down.

"It is all across the north," Pousette said. "And my suspicion is that the B.C. provincial timber supply is global in its influence. And I think what could happen is that the prices could go up."

Prices could go up, Pousette predicted, because B.C. plays such a large role in world lumber.

"There might be a rosy lining for people who own wood lots."

Predicting timber supply in the years ahead is a bit like predicting the weather, he said, and that as social values change that can affect how the AAC is determined.

"We haven't incorporated cumulative effects at all in our timber supply modelling. We talk about carbon, and all those things as they get incorporated... tend to diminish the size of the timber harvesting landbase. At the same time thankfully technology is working the other way."

For example, the province didn't harvest deciduous trees until the late '80s.

As technology improves, it opens up new opportunities to use other parts of the forest that are still only suited for slash piles.

The fact that the licensees haven't used the full amount of the cut - averaging at 10 million cubic metres the last five years - has helped, noted Coun. Frank Everett.

"I think there is a good future for our industry," said Everett, who also noted the drop in licensees in the region from about 16 to about eight or nine now.

Coun. Brian Skakun asked the presenters why there was no mention of First Nation treaties or claims to land in the review.

Pousette said chief forester Diane Nicholls can only take into account "current practice" when presenting her decision, and can't make land use decisions, though he did say public consultations (since April and May) can influence the outcome.

"As soon as those First Nation treaties are signed and if there's land involved in that, then those would be reflected in subsequent timber supply reviews," he said. The province is required to conduct reviews every 10 years.

"We really don't know how much area necessarily will go out with those treaties; it's anybody's guess on that one."

Skakun appealed to the province to step up its support for forestry in the face of hype around liquified natural gas.

"Forestry is a renewable resource and you know what it's the lifeblood of our community and I'm convinced it will be the lifeblood and one of our major economic drivers for decades to come," he said.

"I think the government has to do more to offset some of the negative things that are going on in the declining forest industry."

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)