NEW YORK — Arthouses are closed. Film festivals are

The Criterion Channel, the year-old streaming service, is a hotbed of cinephilia in the best of times. Right now, it’s about as close as you can get to actually going to the movies. Whereas other streamers supply expansive oceans of “content,” the Criterion Channel pools its movies into collections, double-bills and night-by-night selections. Algorithms aren't welcome.

“Instead of isolating each other in our own preferences, we’re coming together around different themes and programs,” says Peter Becker, the energetic president of the Criterion Collection. “I think people can feel that there’s people behind this programming. This is a service that’s programmed by people, for people."

The Criterion Channel, which launched last year in the wake of the shuttering of the Turner Classic Movies-Criterion Collection collaboration Filmstruck, is the streaming arm of the Criterion Collection, the highly regarded maker of robust Blu-rays of classic and international movies.

In its first year, the Criterion Channel has quickly accrued the kind of devoted fanbase that belonged to Filmstruck, the death of which spawned an outcry from Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese and dozens of other filmmakers. Wes Anderson, in a recent piece of fan mail, called the Criterion Channel a “Louvre of movies.” Its many avid viewers include Barry Jenkins, Rian Johnson, Sofia Coppola, Josh and Benny Safdie — and most movie buffs that can afford $10.99 a month.

For quarantined moviegoers, the Criterion Channel is like a warm hearth to gather around while huddled inside. Becker says that in the weeks since lockdown orders began, watching has doubled on the service.

Like a cinema, Criterion Channel has its own weekly listings. Friday nights are for double features. Wednesday belongs to female filmmakers. Matinees of family-friendly movies debut on Saturday. Shorts get showcased Tuesday. And of course, you can sift through and select at will.

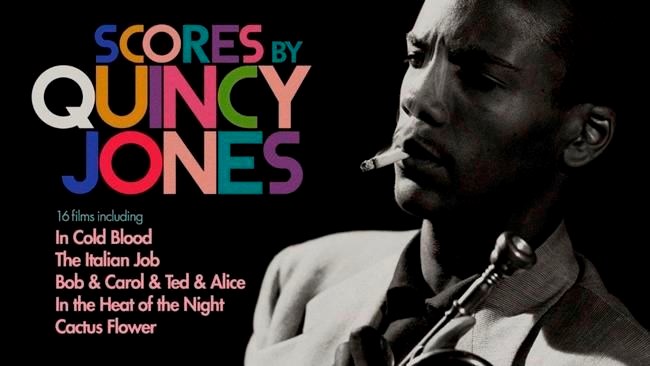

But part of the pleasure of the Criterion Channel is not having to meander through a digital sea of choices. The bedrock of the Criterion Channel, like any repertory cinema, are its series. There have been collections of ’70 sci-fi, films with the scores by Quincy Jones, a centennial celebration of the great Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune, heist movies and pre-code Barbara Stanwyck films.

Most series come with a mix of familiar titles and deep cuts, offering both primers for beginners and discovery for more die-hards. For Criterion’s anniversary, it brought back its inaugural series, Columbia Noir, which pulls together some of the studio’s most heralded film noirs (“In a Lonely Place,” “Gilda”) along with gems ripe for rediscovery (“My Name Is Julia Ross,” “Murder by Contract”). Most collections include video introductions and other supplemental material.

“With the curated collections and the double features and all those ways of presenting the films, the movies feel accessible and they’re contextualized,” says Penelope Bartlett, the channel’s programmer. “There are some good films on other platforms but they’re just there, floating, without much context.”

Bartlett oversees programming but ideas can come from anywhere — other Criterion staffers and sometimes the critics and writers who regularly contribute essays and interviews to the service, like Farran Nehme and Imogen Sara Smith. At a film festival, Becker recalls, “Imogen said the words ‘Western Noir’ and I thought, ‘Oh, Imogen, that sounds fun. Tell me about that.’”

Sometimes the series are inspired by simple curiosity — wanting to know Jean Arthur’s filmography better — or a desire to expand the interest of others. A series in May is planned on trailblazing screenwriter Francis Marion (“Dinner at Eight,” “The Big House”). The digital format and the extensive Janus Films library also offer the chance of spontaneity. When the celebrated Swedish actor Max von Sydow died in March, Criterion gathered together 15 of his films.

“My shtick is I send Penelope emails, usually very late at night when I’ve gone down a rabbit hole, and they have one word with an exclamation point,” says Becker. “I started with, like, ‘Caught on Tape!’ (a series of surveillance paranoia, like Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Conversation”) or ‘Heist movies!’”

Becker declined to share subscriber numbers for the Criterion Channel, which is available in the U.S. and Canada. But he said he couldn’t be more pleased with its growth, and he’s happy for it to occupy a humble space amid much larger streaming-service battles. When WarnerMedia, which is preparing the launch of HBO Max,

“We are still very niche. Being niche is not something that huge corporations necessarily want to be,” says Becker. “But we wear it as a badge of

For Becker, the Criterion Channel also works in tandem with movie

Like Filmstruck did, the Channel features documentary portraits of arthouse

Bartlett says the Channel is weighing other measures, possibly hosting films that had their festival premieres

“The whole point of being a good curator is to suggest some stuff that may light up some of your audience and infuriate other parts of your audience,” says Becker. “You have to risk failure to qualify for discovery. So we’re trying to encourage people to be bold and exploratory.”

The ideas keep coming. The other night, Becker, contemplating the trials of the housebound, sent Bartlett another one-word email. Its headline: “Roommates!

Jake Coyle, The Associated Press