On the ice as a hockey player, behind the bench as a coach and in his job operating heavy-duty construction equipment, Dale Marquette relished his role as a troubleshooter who could make things better.

In hockey, he played every shift with authority - an intense, hardworking winger with a knack for scoring big goals and setting up teammates with pretty passes. He gained a reputation as a skilled gamebreaker with an impeccable work ethic. He was a great protector, always willing to stick up for his teammates, and his fearless approach to the game convinced the Chicago Blackhawks to pick him in the 10th round of the 1987 NHL draft.

Marquette died on March 13 at age 47 of complications due to diabetes, leaving behind his six-year-old son Troy and 15-year-old daughter Jordyn; mother Erika; a sister, Michelle; and three brothers, Dorlie, Dean and Darcy.

As a player and as a coach, Marquette always brought his game face to the rink, an intensity that built the closer it got to the opening face-off. His habit of pacing around the lower concourse outside the Cougars' dressing room before games or between periods was the stuff of legend in the building formerly known as the Prince George Multiplex.

"Dale wore his heart on his sleeve when he played and when he coached and he gave it everything he had and as a result the players fed off that and he got the most out of them because they knew he was fully committed to it," said Mike Hawes, who played against Marquette in the WHL.

Marquette was part of the bantam team that won the 1983 Purolator Cup Western Canadian championship in Winnipeg along with future pros Tony Twist, Craig Endean and Sean LeBrun.

"Dale was your prototypical power forward, he played the game honest and he'd just as soon drop the gloves and be in your face as he would score a goal," said LeBrun. "He played the game exactly as he coached it - like the barn was on fire all the time - and everything he got he worked for."

Ken Antonenko and Eric Henderson coached Marquette on that bantam team and they had him playing on the checking line with Parker Francis and Cam Morris. Marquette still managed to rack up 98 points in 66 games, leading the team in penalty minutes with 146.

"He had a smile that didn't quit and he was a pleasure to coach," said Antonenko. "Dale could handle himself in any situation. He could skate with the top players, and going into the corner with Dale wasn't much fun."

"He was your consummate team player," added Henderson. "He could play both ends of the ice, he was hard-nosed and if you look at his career it pretty much balances out between goals and assists. He was always upbeat, even during tough times."

Marquette left Prince George at age 15 to join the WHL with the Lethbridge Broncos. After two seasons, then-Broncos coach and general manager Graham James traded Marquette to the Brandon Wheat Kings for Sheldon Kennedy. He finished with 51 goals and 103 points in his last season in Brandon and started his pro career in Saginaw, Mich., with the 'Hawks IHL affiliate. The team moved to Indianapolis to become the Ice in 1989-90, and Marquette helped them win the Turner Cup championship.

Injuries forced Marquette to retire from the game the following season, which spawned his coaching career when he was named a replacement coach of the Pacific Valve midget team midway through the 1992-23 season. He took on the job as head coach of the Spruce Kings in 1994 and led them to the Rocky Mountain Junior Hockey League final that season, losing in six games to the Cranbrook Colts. In 1995-96, the Kings captured the Citizen Cup, losing just three games in three playoff series, culminated by a Game 5 victory in Fernie.

"He was a great teacher and I really envied him in the way he approached the game," said Rick Kooses, who coached the '94-95 Spruce Kings with Marquette. "When he walked into those doors to get to the rink, he was a focused man and when he left the rink, he left it there and was a family man, and that's what made him really special."

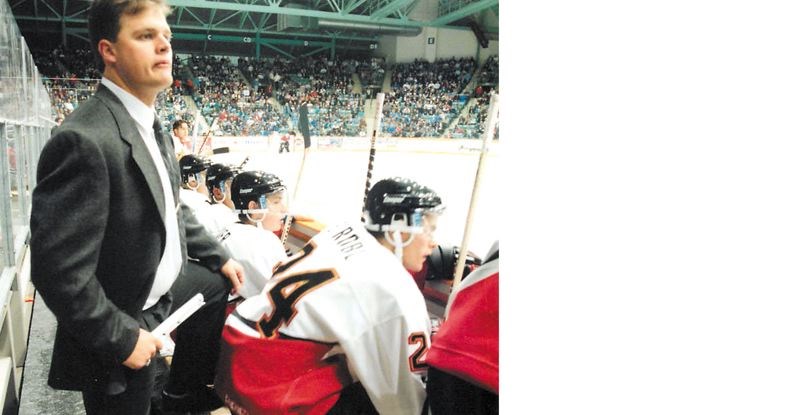

Marquette joined the Prince George Cougars in October 1995, taking over a faltering team with just two wins in 17 games, and they finished out the season with a 15-38-2 record. From the WHL, he rejoined the Spruce Kings two months into the 1997-98 season and got them to the second round of the BCHL playoffs the following year.

Mike Stutzel, who led the Spruce Kings in scoring with 92 points in his last year of junior, was picked up in a trade from Powell River halfway through 1996-97. He went on to play four years at Northern Michigan and signed a pro contract with Phoenix. Stutzel said he would not have had that opportunity if not for Marquette's influence.

"Getting traded to the Spruce Kings was the best thing that ever could have happened and I wouldn't be here if I didn't get traded," said Stutzel in a 2003 Citizen article.

"Dale put a lot of confidence in me. I didn't see eye-to-eye with the coach in Powell River and I had no confidence. I was grumpy and I wasn't having any fun, but Dale made it fun again."

Marquette found ways to poke fun at bad situations, even if it came at the expense of a referee who once kicked him out of a Spruce Kings game. As he made his way across the ice, Marquette donned a pair of sunglasses and pretended he was blind, using a hockey stick as a symbolic white cane to hoots of laughter from the fans.

Marquette was personable, respectful and honest, but there's no denying he had a temper, and the players he coached knew his wrath when they messed up. Dare they show up for practice late, he was known to lock them out of the rink. During a playoff game against Penticton in Quesnel, as punishment for what he deemed a lack of effort while his team was on its way to an 11-3 loss, he locked his players out of the dressing room door between periods.

At his memorial service Saturday, Marquette's ex-wife Lisa Norman told about the day he came home from a Kings road trip without his wire-framed eyeglasses, claiming he'd lost them. He'd gotten mad at his players and to illustrate his point grabbed his glasses and with his powerful hands scrunched them into a ball and threw them away. Unbeknownst to Marquette, his players rescued the destroyed eyeware from the garbage can and had them made into the Temper Control trophy, which they presented to him at the year-end awards banquet.

Marquette's reputation as a great motivator convinced a 0-5 Quesnel Millionaires team to hire him as head coach and general manager in 1999 and he went on to become a coach-of-the-year candidate in the BCHL two straight seasons. His coaching days ended when he resigned from the Mills in 2001.

Marquette left hockey behind and became a sheriff in April 2003 and worked at the job for four years before he joined the city as a landscaper and heavy-duty equipment operator. Known for his mechanical ability, this past winter he was given a plum assignment driving one of city's new Volvo graders for snow removal.

He was a doting father who lived for his kids and without the usual distractions of hockey to fill his days he put that time into teaching family values and life lessons to Troy (the Boy) and Jordyn (whom he nicknamed Goose) and he brought them to family get-togethers with his siblings and their kids, making sure everybody remembered how to laugh.