Before B.C.'s courts granted Wendy Young and Theresa Healy the right to marry, the two used their position as plaintiffs in the historic case to travel the north, educating communities on gay rights and marriage equality.

Friends feared their visibility as spokespeople for the cause, warning they would be attacked, their home firebombed, their pets poisoned.

But most often when they were approached in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it was whispers of thank you. It was stories of children who finally saw some part of themselves staring back from the pages of newsprint, showing two women not just proudly proclaiming their sexuality, but demanding equal rights and equal protection under the law.

A woman approached Healy one day at the Northern Interior Health Unit and Healy felt that familiar fear in the pit of her stomach. Instead, the woman spoke of her daughter, of suicide avoided because she'd read their story.

"It was so unexpected," said Healy. "I did not anticipate us involved in this fight would have actually saved a young girl's life."

Less than two weeks later, a Burns Lake woman said much the same to Young about her niece. These were the little victories the couple held close, long before the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled in May and again in July 2003 in favour of the eight B.C. couples who were petitioning for the right to marry.

That August ,Young and Healy acted as Pride Parade marshals, walking with the crowd to what was then called Fort George Park where they became one of Prince George's first same-sex couples to join in a civil union. A photo from that day, Young in a black tuxedo and Healy in a floral dress, now sits in the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

Today, Healy will walk with their grandchildren in the 19th annual parade, which starts at 11 a.m., and Young will take part in the festival with her warm glass wares and wine jelly.

For the first time, the parade participants will step over a coloured crosswalk, in recognition of the LGBTQ community.

"I think the Pride Parade, I think the same sex marriage case, I think the rainbow sidewalks, all of these things are stepping stones that get us away from a place where you're going to sit in a dark room with a gun and whisky because you hate yourself," said Healy, 62, pointing to just one example of a youth in crisis who called a support line for help.

"It's important for a lot of different reasons, the visibility is one," added Young, 54.

"The presence, that it's permanent. It's not going anywhere.

"Visitors to our community will see it, they're not going to find hate propaganda in stores. They're going to see the pride walk."

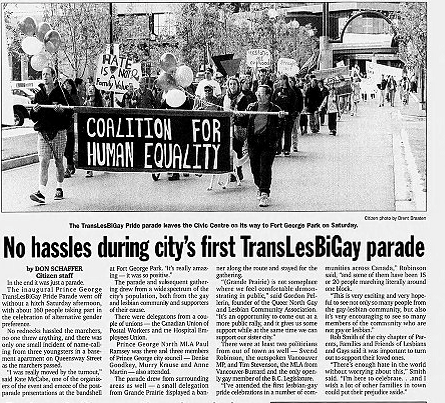

The very first Pride Parade, in September 1997, was in protest of a local business that was producing and promoting anti-gay materials. Months before, Healy and others decided to host an informational picket of the spot, which didn't seem like enough.

"We were talking about we need to do something more proactive and so that's when Pride was born."That first year, Healy recalls protesters lined both sides of Fourth Street, confronting marchers as they turned from the Civic Centre.

The Citizen's 1997 story reported about 160 attended and doesn't mention the poorly made placards Healy remembered, or the laughter as the parade progressed through the protesters.

"As you turned the corner, we saw the misspellings and we saw people who actually looked very sad," she said.

"All of a sudden what we'd been so afraid of didn't look so fearful."

Pride remains political for both women, who invoke the devastation in Orlando, Fla. last month, where a gunman opened fire and killed 49 in a gay nightclub.

"I really want people who are not gay, who are not trans, who are not aboriginal, who are not black, who are not two-spirited, to understand what it's like to walk around with a target on your back and that you never know when that target will be visible to somebody and you will be attacked."

Orlando was as reminder the target is still there.

"It was a reminder that hatred was out there at that level," added Young.

Prince George has come a long way, both said, and so has the region. The two were the only couple from the north named on that landmark case and they saw that representation as vital.

"The message it sent was 'we're everywhere,'" Healy said.

"It's not just these little gay villages, we are in every community. It was a very important symbolic message."

While both have always been social activists, they didn't exactly seek out the position to be that northern couple.

"It just happened. We didn't make a conscious decision about it," said Young, explaining that Gay and Lesbian Association (GALA) North asked them to step forward.

But their philosophy was one of duty, that as strong women from supportive families, they had a position to make a difference.

"For us it's almost a responsibility that we take on, that we are prepared to step forward and be a public face if it's needed," said Healy.

"When we were asked to the be the northern plaintiffs, we didn't even know if we wanted to get married," said Young, who had long felt their commitment ceremony in 2000 represented their union. "The part that annoyed the both of us was that we didn't have the choice."

At the time, not everyone in the community agreed with the fight toward marriage equality and saw it as working within the system, within patriarchy, and the wrong way to create a changed world.

"We began to realize that marriage is a very radical act and it's always been denied to marginalized groups," said Healy.

They trip over each other's sentences to explain their own realization around their civil union.

"The legality component was important," said Young as Healy added. "More than we thought, I think."

"Yeah. I didn't realize," started Young as Healy finished, "What it would mean."

It meant they no longer existed as second-class citizens, that if one was ill, they would be granted the right to see their loved one in the hospital.

While Young doesn't overthink their place in the queer fight for equality, Healy, a UNBC professor, has considered the impact.

"I'm a historian and I like that we're going to be a footnote," she laughed.