Cold, wet and shivering, Tony Bourdeau felt like he was going to die.

His mind lapsing in and out of consciousness as his body temperature plummeted, Bourdeau looked over at his hunting companion, 14-year-old Matthew Knight, and told him to leave to try save his own life.

But the Prince George teen refused to go, instead trudging back and forth through waist-deep snow in a blinding storm to build a fire and shelter and collect enough wood to survive the night. It made all the difference in the world to Bourdeau.

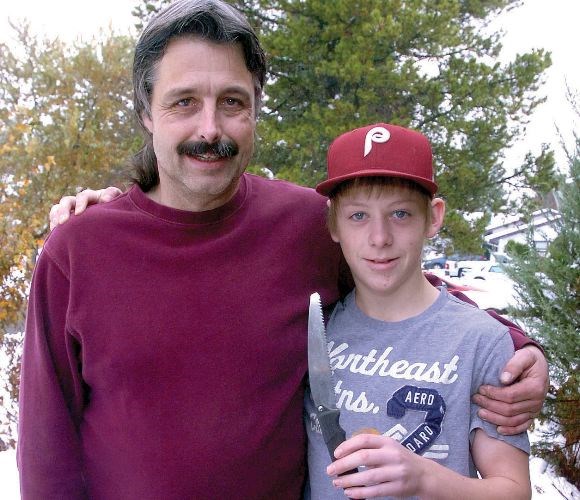

"He saved my life, I thought I was a goner," said the 50-year-old Bourdeau.

Their 17-hour ordeal on Oct. 27 while elk hunting northeast of Chetwynd started at about 2:30 that afternoon when they spotted a group of three hunters using a rope to haul the quartered sections of an elk up a steep slope that led down series of ridges to the Pine River. The other hunting party said there were several elk in the area and Bourdeau and Knight parked their quad on the road, Knight grabbed his rifle and they headed down the hill.

As they got closer to the river they saw several animal tracks in the snow and knew they were close. Knight scoped out a bull elk about 3,000 metres away but didn't think he could hit it from that range and they started moving closer through the thick brush. Knight spotted the elk again but there were too many trees in the way and he didn't shoot.

They continued their pursuit through the snow until Bourdeau unwittingly found a swampy area and plunged into icy water up to mid-thigh depth into the icy water. He managed to keep one leg dry from the ankle up, but the air was air chilled to -17 C as he walked through the deep snow into the face of a steady wind. The muscles in his legs started to freeze and after walking only about 50 metres he could go no further. They had been chasing the elk for 90 minutes and faced a series of switchbacks through the snow to return to their quad two kilometres away. But there was no way Bourdeau could make it. Not through all that snow.

"It was getting dark and we should have been out of there a lot sooner," Bourdeau said. "I knew I was wet already and I was in trouble. My legs were seizing and I was scared, but Matt was calm and he just said, "We better get a fire going.'"

Warned about the dangers of hypothermia by his dad and from what he learned as an outdoor education student at Kelly Road secondary school, Knight took action. His dad told him to always wear his knife with him in the woods and he had it in his pocket, one that came in a leather pouch with an interchangeable sawblade. Another hunter had given him the knife three weeks earlier while on a big game hunt near their home at Ness Lake and Knight used it to cut some birch bark for a fire.

Bourdeau lit one last cigarette then handed the pack and his lighter to Knight. By that time, it was snowing heavily and with difficulty, they managed to spark the crushed-up tobacco enough to ignite the wet wood into a flame. Knight found a dead tree standing and used the sawblade to cut small pieces to throw on the fire. Despite his best efforts, he was unable to build it into a big blaze. Eventually, the tree stump they'd used to keep the heat confined caught fire and started giving off sufficient heat for Bourdeau to take off his wet pants and coat to try to dry them with his soggy socks and boots.

Back at their camp six kilometres away, Bourdeau's brother-in-law, Phil MacBride, knew something was seriously wrong. Two hours earlier, at about 4:30, with storm clouds descending, he'd seen through his binoculars Knight and Bourdeau going after their elk and was waiting for them to herd the animals to where he waited with his rifle. Not long after, MacBride heard two gunshots, followed a few minutes later by a third, and assumed it was Knight shooting his elk, wounding it with the first two shots, then firing a third shot to finish it off. What he didn't know was Knight was trying alert the other hunters to their emergency with three shots in quick succession -- the universal distress signal. But on the third shot his gun jammed, and he was unable to fire it again until several minutes after the sound of the first two rounds pierced the air.

Knight's father Rick tried to stay positive the two hunters would find their way back to camp to join him and the rest of the crew, but as the night grew long he knew that wasn't likely to happen until daylight returned. He and Bourdeau met for the first time the day before and he had no idea what kind of survival skills the man possessed, which added to his worries about his son's safety. At 10:30 p.m., MacBride used his cell phone to call 911 and after the initial dispatch was sent to Fort St. John Search and Rescue a member of the Chetwynd Search and Rescue team phoned in to say he was closer and knew the area well and would respond for the search as well. An RCMP officer from Chetwynd joined the husband-and-wife search team from Chetwynd, Don and Kim Wheeler, who arrived in a pickup truck at about 4 a.m.

The snow had continued through the night and Bourdeau couldn't stop shivering. The fire was melting snow which dripped on his head from the tree boughs above him onto the wet ground where he huddled. Knight came back with more strips of birch bark to help insulate the ground, and when he wasn't cutting wood, Knight would come over to wrap his coat over Bourdeau while rubbing his shoulders and arms to provide heat. Just having another body there to lean on and dry his wet hair occasionally was a comfort that kept him alive.

"I panicked a lot and he stayed so calm," said Bourdeau. "I think I was a bit delirious and he kept telling me to move my feet and hands to keep from getting frostbite. He had enough will to keep us both going."

At about 11 p.m., the hunters in camp fired off three S.O.S. rounds, which the stranded hunters heard. Knight fired back, but the ridges in front of them blocked the sound of their rifles and his shots couldn't be heard above the snow and howling wind. By the end of the night, Knight had fired 15 shots, to no avail. They had seen the lights from the quads of the other hunters looking for them but it was so steep, they could not be seen and they had no way of signaling them.

"We knew they weren't coming for us that night and I was shaking because I was scared," said Knight.

Knight cut some trees to make a lean-to but couldn't find any pine boughs that would have given Bourdeau better shelter from the falling snow and a cushion of needles to help him dry out. He built up a pile of firewood and at about 9:30 a.m. Bourdeau convinced him to leave to go get help. Knight had been gone about 45 minutes when the burning stump fell over, knocking the lean-to down onto the fire and smothering it.

At around 11 a.m., Knight reached the railway tracks and was standing there when he saw the search and rescue truck, 300 metres away. They saw him and he took off running towards the truck. Knight told them where Bourdeau was and a helicopter was dispatched from Yellowhead Helicopters base in Fort St. John.

By that time, the other hunters had packed up their gear, and after a joyful reunion in camp, Knight's father Rick gave Matthew a big bear hug and was astounded with what he had to say next.

"The resilience of a kid is amazing,' said Rick. "The first thing he said after we finished hugging was, 'We're going now? We're not going to stay?' We'd planned to be there hunting for three days and he wanted to stay another day.

"I'm just so thankful they got back, I've never been so scared in my life."

It was about 10-minute helicopter flight from Fort St. John and poor-visibility conditions made the flight into the area difficult. A four-person search and rescue crew retraced Knight's tracks and found Bourdeau, wrapped him in a sleeping bag, and started carrying the 220-pound man on a backboard. It was a tough haul getting him up the hills through snow and they were joined by a couple of hunters who helped carried him to the road, where he was loaded into the helicopter and transported to hospital in Fort St. John.

"That helicopter was probably the difference between me living and dying," said Bourdeau. "It was a lot of work for search and rescue to haul me out of there through waist-deep snow and a lot of deadfall and I could tell they were struggling."

After spending a day in hospital, nursing burns where his underwear and hoodie had melted onto his skin as he hugged the fire, he was driven back to Prince George, and returned to work last week as sheet metal mechanic.

"I'm still having nightmares about it -- I think I need to talk to somebody professional about it, because I think I came pretty close [to death] there," said Bourdeau.

Knight and Bourdeau agreed the one big mistake they made was leaving their fanny pack loaded with survival gear back at the quad. In that pack was a foil space blanket, waterproof matches, fire starting material, a rope and flashlight. Knight also forgot his cell phone in his dad's camper, which cut off his lifeline to the outside world.

Bourdeau is an avid ice fisherman and on Saturday in his first meeting with Knight since their trip he asked if he'd like join him to drop a line in Ness Lake. He knows he has a new friend for life to share his love of the outdoors.

"Matthew and I talked about a lot of things that night and we became pretty close and now it's like I've known him all my life," he said.

"He's a hero."