The capital dollars are in place and the design is almost ready for the proposed $3.2 million white sturgeon hatchery in Vanderhoof, but Brian Frenkel is disappointed the operational funding is taking so long to secure.

Proponents expect it will cost about $800,000 a year to operate the facility, which they believe is essential to save the critically endangered fish species from extinction in the Nechako River.

"We've been working on this for a long time and we've been close a couple of times," said Frenkel, a councillor with the District of Vanderhoof and chairman of the community working group on the hatchery project. "It doesn't mean we've given up by any stretch. We're frustrated by how close we are and the fact there's been no official announcement saying we're building it and we're building starting tomorrow."

Funding proposals have been prepared and negotiations are ongoing with the provincial government and the Nechako Environmental Enhancement Fund.

The fund has offered to pay about half of the required costs for 10 years, according to a draft report presented this spring. The final report is expected to be completed later this summer and if funding for the sturgeon project goes through it would still be conditional on matching funds from another source.

About half of the annual operational funds will go towards staffing and running the hatchery as well as monitoring the fish after they've been released. The other half will be directed towards further research.

The final design plan for the facility is still about a month away, according to Cory Williamson, facility development manager for the project. Once that's in place, the final capital costs can be calculated, but Williamson expects it to be inline with the $3.2 million already set aside for construction.

The longer the project is stalled, the more the current population of sturgeon in the river ages. It's estimated that the number of adult sturgeon has dropped from 8,000 to about 400.

Williamson said the sturgeon haven't spawned successfully in the river for four decades.

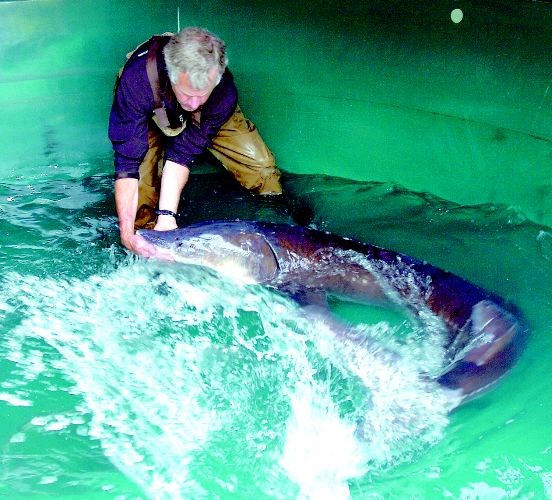

"We have an aging population of fish that the vast majority of which are older than 40 years," he said. "Sturgeon typically live up into their 60s, 70s and 80s. We have a group of fish that are slowly getting older and older and older and don't have a proper place to spawn at the moment."

Due to changes in the river flow over the years, much of the sturgeon's typical spawning grounds have been silted over. Sturgeon spawn in gravel and the larvae use the space between the gravel stones to hide from predators -- but when the gravel is covered in silt they have no place to hide and they are consumed before they have the chance to mature.

Once the hatchery is up and running, scientists would acquire eggs from mature fish in the spring and fertilize them. The larvae would grow in the hatchery for a year until the reached about one pound, at which point they'd be released back in the river.

At the same time, work will be done to create a suitable spawning habitat so the hatchery-raised fish could reproduce on their own.

"We think with some habitat restoration measures on a large enough scale, we can bring this population back so they can actually spawn naturally," Williamson said.

Frenkel said he thinks the federal government and business groups need to step in and help fill the funding gap.

"This whole area is engaged in saving this species," he said. "It runs right through our community and yet I don't see anything out of the feds, I really don't. Does saving species fall on the backs of the people that live and around them or is it a federal or provincial responsibility?"