Former Prince George resident Amber Faktor was at home alone in Sandspit when a 7.7 magnitude earthquake hit 40 kilometres south of the small Haida Gwaii community on Saturday night.

For Faktor, who moved from Prince George to Sandspit in May to work for Moresby Explorers Ltd. -a local boat tour company - it was her first experience with an earthquake.

"I was at home, which is an apartment above where the office is. We're right on the water front," Faktor said. "It just started shaking,. It lasted for about a minute or two. About halfway through the power went out, which was freaky because it was pitch dark. There was glasses falling and breaking all around me."

Faktor said she was able to make her way to her way to her bedroom and find a headlamp so she could see.

"After it happened I was a little shaken up. Being from Prince George, earthquakes aren't something I've experienced," she said.

She tried to use the landline telephone to call an acquaintance in Sandspit, but the phones were dead. However, she was able to use her cellphone to get in touch with someone.

"They said, 'Get in your truck and drive to Hydro Hill,'" she said.

Hydro Hill is the designated tsunami gathering point for the town of just over 500 people, she said. The narrow, steep dirt road leading up the hill was busy with trucks and cars as residents fled from low-lying areas.

"It was pretty much the whole town. It's a pretty well-rehearsed drill here," she said.

Most people stayed in their vehicles to shelter from the wind, until about 11:30 p.m., when the word was spread that the tsunami warning had been downgraded to an advisory.

"Then we were allowed to go home," Faktor said. "Thankfully the power had come back on, so I could see. There wasn't a ton of damage. Books were strewn on the floor, glasses had fallen off the shelf in the kitchen."

Faktor said she spent a restless night, because multiple aftershocks kept her awake.

"It was probably at least one an hour. It's continued all through today," she said. "There was two or three substantial ones - they shook the whole house again."

The U.S. Geological Survey reported over 30 aftershocks in the region, ranging from magnitudes of 4.0 to 6.3.

In Prince George residents reported mild shaking but no significant damage.

"My chandeliers were swaying from side to side," Prince George resident Louise Burns said. "It felt like we were on a boat. It must have lasted two or three minutes."

In Prince Rupert, 202 km from the earthquake epicenter, residents were evacuated from streets close to the water and brought to the city's main recreational facility, the Jim Ciccone Civic Civic, said Rudy Kelly, the municipality's director of recreational and community services.

"It was a serious tremor," said Kelly on Saturday night. "Now we're waiting for everyone and praying within hours we'll hear from the Island it's just a big wave rolling in."

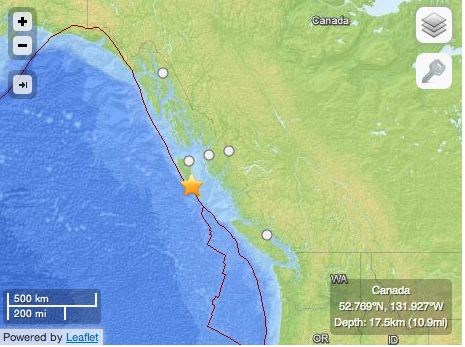

The main quake struck Saturday evening a few minutes after 8 p.m., with an epicentre about 30 kilometres off the coast of Haida Gwaii, formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands.

It triggered tsunami warnings along the B.C. coast and as far away as Hawaii. There were reports of people feeling the quake throughout B.C., though there appeared to be no injuries or significant damage in the immediate area beyond broken picture frames and dishes.

The largest wave associated with the quake hit Langara Island, a northern Haida Gwaii island, and measured just 69 centimetres.

The area is a hot spot for quake activity, with a major fault line just off the coast of the islands that make up Haida Gwaii. It's the same area that saw Canada's largest earthquake ever recorded, a magnitude-8.1 quake in 1949.

Saturday's earthquake was Canada's largest since that 1949 quake, said John Cassidy, a seismologist with Natural Resources Canada.

"This was a huge earthquake - a magnitude 7.7 is the type of earthquake that only happens maybe one or twice around the world each year," Cassidy said in an interview Sunday.

"It's Canada's equivalent to the San Andreas Fault."

The quake happened as two tectonic plates - the Pacific plate and the North American Plate - slid past each other. Cassidy said such horizontal movement typically doesn't pose the same tsunami risks as vertical movement, which is the sort of quake that triggered the devastating 2010 tsunami in Japan.

It was followed by "hundreds and hundreds" of aftershocks, most of them too small for anyone to feel. Cassidy said those aftershocks were expected to continue for days.

The quake invariably prompted speculation about the "big one" - the type of earthquake that is believed to strike off the West Coast every 500 years or so and would create a massive tsunami and cause significant damage in British Columbia and the northwestern United States. The last one was in 1700.

Brent Ward, an earth scientist at Simon Fraser University, said the big one would happen along a different fault than the one involved in Saturday's quake, on the edge of the Juan de Fuca Plate west of Vancouver Island.

That plate is moving underneath the North American Plate, said Ward, in a process known as subduction. When it finally gives way, the results would be catastrophic.

"We would get the entire West Coast of Vancouver Island being affected by a large tsunami, similar in size to the one that hit Japan," he said.

"We would get intense ground shaking throughout southwestern B.C. down into Washington and possibly into Oregon, so we would see a very huge area affected by damaged buildings, damaged roads and bridges. There would be fatalities."

But Ward cautioned against focusing too much on the big one. He said smaller - but still destructive - quakes are likely to be more frequent, pointing to a magnitude-7.3 quake that struck underneath Vancouver Island, near the community of Courtenay, in 1946 as an example.

The damage in 1946 was considerable, and Ward said it would be worse today with the island more populated than before.

"Everyone's concerned about the big one, but the ones that are similar to what happened under Courtenay, these happen every 40 or 50 years," said Ward.

"If you compare similar sized earthquakes and the damage they do, it would be a very significant event."

While the fears of a tsunami were never realized, there were concerns that information from the provincial government's emergency program was slow to reach local officials.

Justice Minister Shirley Bond, whose ministry oversees the province's emergency program, said the government will review what happened, but overall, she said she was pleased with the response.

"We're continuing to analyse the response as we work our way through the day. Local authorities responded well, and their emergency plans seem to have worked well," Bond said in an interview.

"Obviously, minutes and hours matter when there is a potential catastrophic event, so what I want to do is refine the process so that we do that as well as we possibly can."

Bond declined to offer her own assessment of the province's performance, preferring to leave it up to the government's review.

-- with file from The Canadian Press