Northern B.C. communities continue to have volatile populations and housing markets, but the current building trends are mimicking past practices that don't cater to the needs of changing demographics, especially with seniors.

In Prince George - like the many northern towns - the choices are scarce and the housing is old.

Accessible and affordable housing is a key factor to attracting both investment and creating an environment where people will stay long-term, argued Community Development Institute co-director Marleen Morris.

On Friday she presented the Northern B.C. Housing Study, which drew on recent data from 10 communities to offer a picture of the rental and housing options for residents and newcomers.

"Attracting people to fill jobs, attracting people to invest... is critically important if we're going to leverage this economic activity," Morris told the more than 100 gathered in Canfor Theatre to listen to the results. "If we don't have a good supply of first rate homes ... they won't come."

"Housing is literally a pivotal issue."

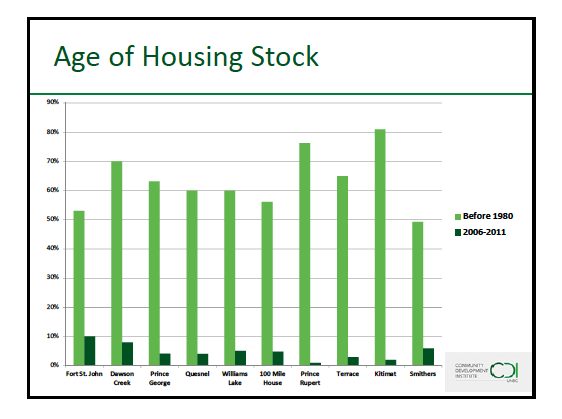

New housing is scarce, with the majority of homes over 35 years old. Sixty-three per cent of Prince George homes fit in that category, though they were considered in good condition. In Prince Rupert, only one per cent of homes were built between 2006 and 2011. Kitimat is the worst for old homes, with 80 per cent of its homes built before 1980. Houses built predominantly in the 1960s and 70s don't suit the current needs and too often those same designs are adopted today. That approach doesn't appeal to the skilled professionals communities are trying to recruit, it said.

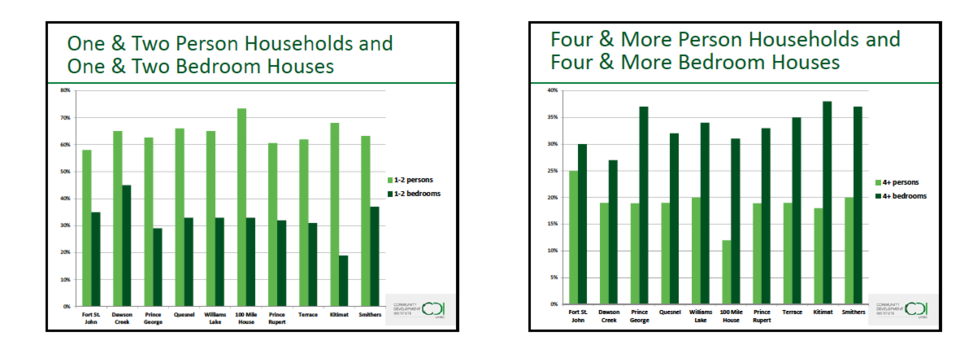

In particular, homes are still built to accommodate four and five bedrooms when CDI is seeing increasing demand for one and two-person households, creating a mismatch between housing stock and household size. That's due to "empty-nest seniors and people in the family formation years who are delaying having children," the report said.

Prince George, Dawson Creek, Kitimat and the other CDI studied were selected as "bellwether" communities on the edge of change, with "something to teach and show us."

Many are highly dependent on the state of the resource sector and exhibit boom and bust trends even in a small time frame. Between 2011 and 2014, four of the six communities grew, while six contracted. That trend shifted more recently, between 2014 and 2015 when only two grew and six contracted.

But overall she said communities are growing, with the average growth at 10.2 per cent for the region. Because communities economies seem to rise and fall, rental markets are also volatile, with limited options for newcomers in many cases.

"It's not cheaper to live up here," she said.

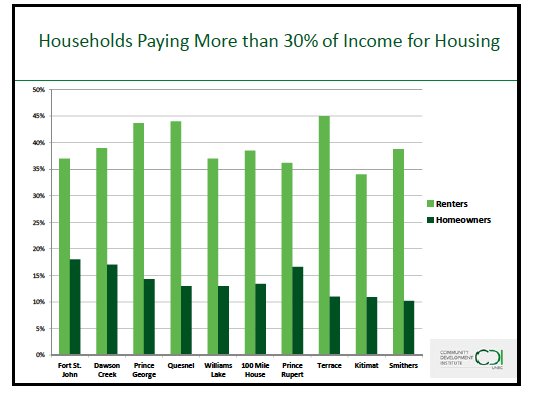

Renters are far more likely than homeowners to pay more than the recommended rate of 30 per cent of their income on housing. And the cost can dip and hike dramatically year-to-to year. Fort St. John continues to be the most expensive for both housing and rental costs. In June 2016 the average to-date selling price was $405,421 and the average rental in April 2015 was $1,013, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation - comparable to Vancouver rates.

To stress that rental volatility, Morris showed a graph comparing Dawson Creek and Terrace, which showed the highest and lowest vacancy rates for 2015. In 2012, Dawson Creek's vacancy rate was three per cent, but three years later that had tripled to nine per cent vacancy.

Prince George saw its population decrease in 2014 after the economic downturn, the report found.

"Despite the economic downturn, Prince George benefited from a small boom in residential construction, which resulted in 689 housing completions since 2013," it said.

And, two-thirds of Prince George's housing stock is single-detached homes; only 13 per cent are apartments. Prince George and other communities need to plan for an expected spike in the senior population, with some communities seeing their numbers double.

"Are our communities ready for this?" asked Morris, adding many seniors are stuck in large homes when they would prefer to downsize.

In Prince George, the population is expected to decrease by 2 per cent over the next 20 years, but the number of seniors is forecast to grow by 74 per cent, the report said. Communities need to become more age-friendly, and Morris argued that is in their benefit because seniors are more likely to spend locally and represent a business opportunity for services that cater to their needs.

Morris said CDI purposefully didn't offer solutions because they will have to specific to the community context. It's role will be sharing the information and increasing awareness around options to support innovation in the building industry.

"It's hard to make the numbers work," Morris acknowledged of the northern housing economy, but she said she hopes this conversation will prompt work towards a "stronger, more resilient, more robust" market.

The study involved 10 communities in northern B.C.: 100 Mile House, Dawson Creek, Fort St. John, Kitimat, Prince George, Prince Rupert, Quesnel, Smithers, Terrace and Williams Lake.