Today, a graveyard is all that is left of the Lheidli T'enneh Indian village at Fort George Park.

But until the village was purposely set on fire in September 1913, after the residents had been evicted from their homes and relocated to the Shelley reserve, the settlement was a focal point of the lives of the First Nations people who lived at the confluence of the Nechako and Fraser rivers.

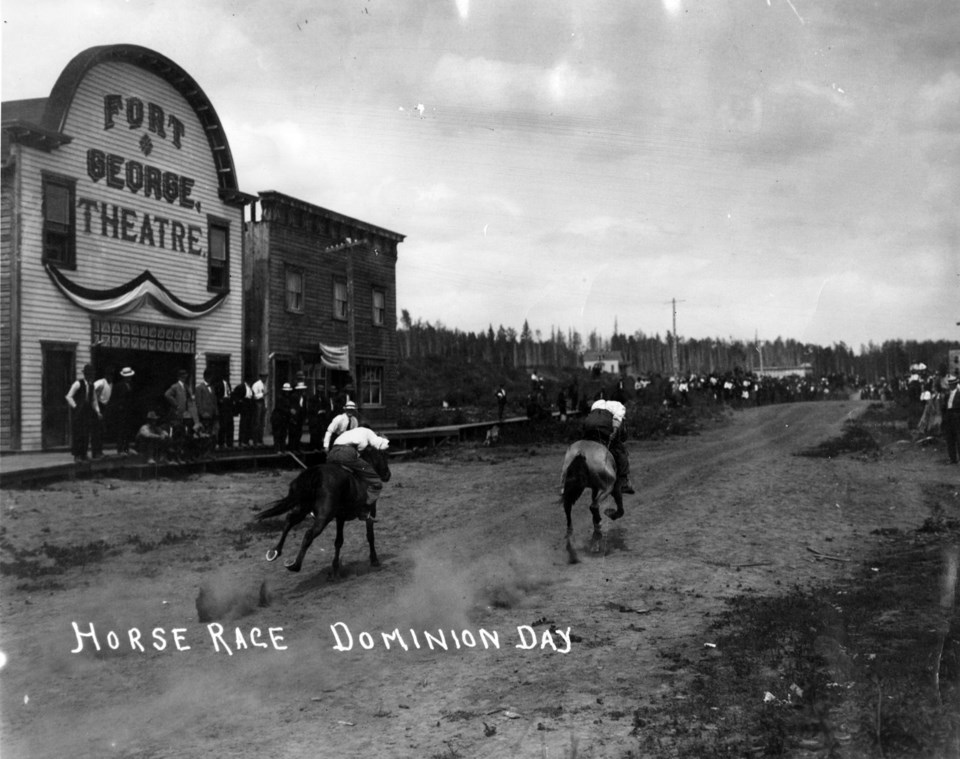

The proof is in the pictures available on The Exploration Place museum website at www.theexplorationplace.com. Photos of First Nations people at Fort George and the surrounding region that date back to 1900 are featured on one of the museum's themed online exhibits -- Settlers Effects.

In the shadow of the Hudson's Bay fort to the south, the Lheidli people built houses on traditional territory that stretched to the border of the future rail yard. In that village, they dried and stored fish in caches, saddled their horses, grew potatoes, and attended mass at St. Francis church, until they were bought out and forced to resettle.

"They burned everything, so they couldn't come back," said Bob Campbell, manager of curatorial services at The Exploration Place. "The photos of them actually burning the village are supposed to exist, but I've never seen one. It's a tragic story. The week after they moved the First Nations people they had an auction on George Street and raised $1.5 million."

Glimpses of what the community looked like before Prince George was incorporated in 1915 are on the website. The pending arrival of the railway in January 1914 resulted in land speculators moving in, and they bought up property in a battle among the three Georges (Prince George, Central Fort George and South Fort George), a fight that lasted several years until the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway picked Prince George for its First Avenue train station. Once it was determined Prince George would be the site of the train station, most of the businesses in the area set up close to the city's current downtown area.

"By 1915, South Fort George was almost a ghost town," said Campbell. There were still people living in the houses but most of the businesses were vacant and we know that from the fire insurance maps (available on the website) of 1916."

People now know the western boundary of Central Fort George as Highway 97 or Central Avenue, but in August 1920 that stretch of road became the city's first aircraft landing strip when four Black Wolf Squadron biplanes of the U.S. Army Air Service visited Prince George en route to Nome, Alaska. Campbell explained the story of one of the planes hitting a stump as it landed, tearing off a wing. A local cabinet maker was called into service and rebuilt the wing, but was unable to tighten the canvas skin and the pilot ended up leaving for a shaky flight to Vanderhoof with one floppy wing.

The website is a public pipeline into the E.F. Ted Williams History Centre database, which has thousands of searchable photos and cataloged items, including many images that appeared in the Citizen. The search software has a built-in feature that inserts wild card words at the beginning and end of search words to help people unsure of spellings, to allow for alternate spellings, plurals, or if only part of a term is known.

"It could be a paddlewheel boat, or a sternwheeler, or a steamer, or a riverboat, all describing the same thing, so you might have to try a few things," said Campbell.

Former Citizen photographer Dave Milne, who retired in 2006, learned shortly after he started with the paper in 1970 the 8 X 10 photos printed by all Citizen photographers for use in the paper each day were being tossed out after they were used. He began taking those pictures home and kept saving them for the next two decades until the Citizen went digital in 1990. When Milne decided to clean out his garage, he obtained then Citizen publisher Del Laverdure's permission to donate his collection to the museum, along with boxes of photo files and negatives that had been stored at the newspaper.

"On the back of them, the date is stamped on, the photographer's name is there and often the caption is there -- it's rare to get that much good information," said Campbell.

"It's a marvelous collection, and almost every picture is unique, because they are the blowups, and it covers everything possible. We're working on scanning them into the database and putting them online."

The Exploration Place also has 37,000 negatives of Citizen photos from 1968-68 which are archived in binders. Only about 250 of those images have been digitally scanned.

The museum welcomes the loan of historical photos for scanning, which will then be returned to their owners.