Fourteen years ago, Don Callaghan woke up in an unfamiliar bed and had no idea why he was there.

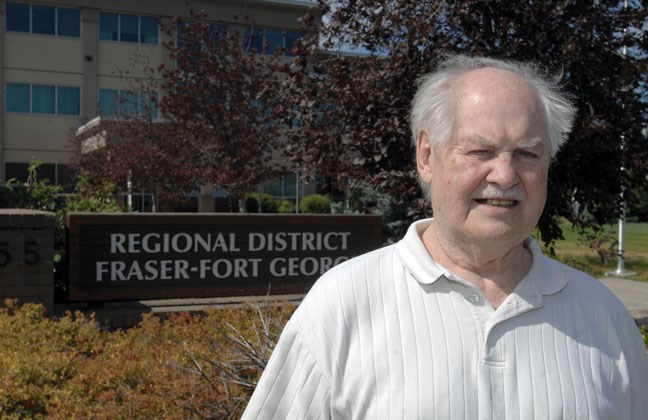

The Fraser Fort George Regional District board member from Bear Lake began searching for clues, hoping he would find his bearings.

"I'm looking around the place and then I hear some voices and I realize they belong to friends of mine and everything starts to fit into place," Callaghan recalled. "But I still don't have the foggiest clue why I was there."

Callaghan made his way from the bedroom to the living room, looking for more answers. He expected his friends to be surprised by his presence in their home, instead they were shocked he didn't know why he was there.

Such is the mystery of a brain injury.

The symptoms vary from person to person and can evolve over time. They don't always present themselves immediately, but for many people with the condition once they appear, they never go away.

In Callaghan's case, he was about a week removed from getting hit by a truck in Bear Lake. He had been released from hospital, but doctors had advised him to stay with friends in Prince George in case he needed follow up care.

Up until the point he woke up in the bed, Callaghan had appeared to be recovering well, his friends told him later.

Now, nearly a decade and a half after the accident, he is still suffering the after effects.

"It's not like you forget something," he said of the memory issues that continue to plague him. "It's just a hole, like a proverbial black hole in space."

The symptoms of his brain injury eventually led him to relinquish his seat on the district board because he couldn't concentrate long enough to sit through a meeting. He also needed to develop new skills to cope with constant memory loss and fatigue.

Callaghan is one of many clients of the Prince George Brain Injured Group (PGBIG) who spoke to The Citizen as part of series of stories exploring what it's like to live with an injury that is often invisible to people on the outside, but life changing to those who suffer from it.

They spoke about how they acquired their injuries, the recovery process and what it's like to adjust to an entirely different existence in a world where a stigma still surrounds their ailments.

Jim Switzer has learned to cope with anger issues that sprung up after his 1998 workplace accident, while Ingrid David had to learn how to cook again after a gunshot wound to the head in 1975 took away her sense of smell.

Each year, about 22,000 British Columbians suffer a traumatic brain injury, according to figures from the Northern Brain Injured Group (NBIG). They can occur from almost anything from sports injuries to motor vehicle collisions to workplace incidents and aneurisms.

A brain injury diagnosis can be scary because so much of what lies ahead for the patient is unknown and the timeline for progress is uncertain.

It can be tough on family members who have to deal with a person who is no longer the same and marriages often dissolve as a result. Friendships are tested and sometimes broken because it's difficult for anyone to relate with with the brain injury.

It's also challenging for a community to provide the long-term support to help people heal from the injuries, cope with the ongoing symptoms and flourish in their new reality.

This year, PGBIG is celebrating its 25th year in Prince George, offering counselling, employment and group home services to dozens of clients. Each brain injured person uses the services in a different manner. Some prefer the camaraderie of being around other people going through similar struggles, while other clients enjoy the practical skills they can pick up in group counselling sessions.

Switzer suffered his injury in the spring of 1998 after falling down the stairs at his workplace in Aldergrove. He wasn't found until the next day by his manager and was rushed to hospital and considers himself lucky to be alive.

Like Callaghan he woke up in an unfamiliar locale, but was quickly able to deduce it was Vancouver General Hospital.

"All I knew is that I was told I had a brain injury," Switzer said. "I said, 'what the hell is a brain injury?' I couldn't figure it out. The only thing I can figure out is what I can do and what I can't do."

He moved to Prince George in 2000 after someone recommended the services of PGBIG and has been a regular around the community service organization ever since.

PGBIG offered him the chance to keep busy by doing odd jobs like handling their recycling activities or labeling videos.

Switzer enjoys the work, especially because it keeps him away from big groups, since crowds are something he's been unable to handle since his injury.

A counsellor at the agency also taught him techniques to deal with his anger issues.

"I usually go home and sit there because a woman that was here a long, long time ago, she told me it would help if I went home and sat there," he said. "If for two or three days they don't hear from me, then they will come and check on me."

Angry outbursts were never a problem for David, who had been a nurse in Dawson Creek before she was shot in the head during a burglary attempt when she was 33 years old. She was found by her husband Fred and two young daughters, aged four and eight at the time.

During her 52 days in an Edmonton hospital, she had to learn how to speak again.

That was just the start of a recovery that continues almost 40 years later.

She had to learn to cook again because when she lost her sense of smell, she found herself burning meals. She adapted with the aid of a timer.

She also finds it difficult to communicate, sometimes forgetting what she's going to say or making leaps of logic that other people don't get.

"When it comes to jokes," she said, "I can never remember the punch line."

Having a young family at the time of her injury was both challenging and a blessing. She had to quit her job, but taking on the role of housekeeper gave her the inspiration to push through the hard times.

"I had to get [the children] off to school in the morning, cook for them, keep house, do their laundry," she said. "As they approached their teens they needed me less and less, but I probably needed them more."

David, Switzer and Callaghan have all made progress over the years, learning different tricks to get through the roadblocks that are put in their paths.

For 2 1/2 years, Callaghan didn't drive, because he knew his brain couldn't process things properly to operate a vehicle safely, but the 73-year-old is back behind the wheel now.

His attention span is short and he gets fatigued quickly, so he devised a plan to test himself on long road trips to make sure he's up to the task. Whenever he comes across a sign giving the number of kilometres to the next town, he converts that figure to miles in his head.

"The ease or difficulty that I have in doing that tells me if I should be taking a break or stopping," he said. "If you have to work at it, that means you need a break and if it's a jumble of numbers, that means your driving for the day is over."

Although he can't do everything he used to, Callgahan has come to accept where he's at and live within his limitations.

"I've learned the slot where I live,"he said.