Captain Ian Bruce Macaskie was an officer with the Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment.

He was with the British Expeditionary Force in France and was captured by the Germans during rear-guard action in 1940. He spent five years in prison camps.

After escaping three times, he was finally sent to Colditz Castle until he was released at the end of the war.

During Macaskie's time in the prison camps, he put pen to paper, both writing about his experiences and drawing cartoons.

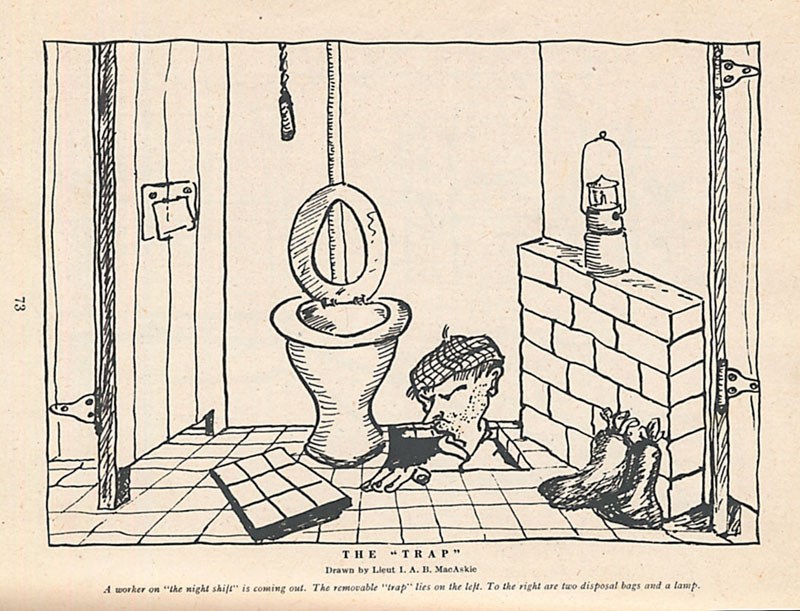

"The Canadian Red Cross put out a book to raise money," said Karin Yarmish, Macaskie's daughter. "My dad has a cartoon in there."

It's a cartoon of a prisoner of war trying to escape by digging a hole beside the toilet in a wash room.

"He created a whole bunch of little drawings about life there," said Yarmish about her dad, who passed away in Prince George on Sept. 22, 2005 at age 86.

After the war, Macaskie immigrated to Canada and joined the B.C. Forest Service, working with them for seven years in Prince George, Aleza Lake and Penny.

From 1958 to 1978 he was affiliated with the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, where his work included studies on the stellar sea lion, sea otters and killer whales.

Macaskie and his wife, Tina, enjoyed 60 years of marriage, said Yarmish, who was their only child.

She learned early that the war was not a favoured topic of conversation with her dad.

"He didn't talk about it a lot and I didn't ask a lot questions," said Yarmish. "As he got older, little snippets would come out."

Macaskie, who suffered from terrible nightmares after the war, never wasted food and kept everything that could be deemed useful.

"My father did not care about material possessions and appreciated his freedom, the wilderness, space and solitude," recalled Yarmish.

Yarmish and her husband David recently joined the Royal Canadian Legion to honour her father's memory and the many others who made the sacrifices for all of us, she said.

"And we need to remember that, not just on Remembrance Day but every day."

Here are two excerpts from Macaskie's journals Yarmish shared with The Citizen:

Homesickness, Colditz Castle

It is not often that I think of home. In the early days of imprisonment, food, and the lack of it, was the main consideration, whereas now I bury myself in literature or art or technicalities and have become so enured to this way of life that the world outside these walls appears unreal and vague.

But occasionally, and fortunately seldom, the amour is pierced. Sometimes a thrush singing on the roof tops, a moonlit cloud or just the smell of soap is sufficient to tear aside indifference and leave a wound.

All in a moment I am sickened by the awful monotony of the passing years, tired of the study of this or that subject and conscious of the many futile months to come.

I lay in my narrow bunk and someone plays a tune on an accordion. A poor rendering perhaps but a note or two strikes deep and stirs up a sleeping memory. Dearly then would I count my freedom. I want to walk along the river bank, I want to hear the waves breaking on the black rocks and the wild geese winging overhead. I want to see you, to talk with you, to smile again with you.

Then the vivid scenes fade and with them goes the pain. Reality demands that I wait yet awhile longer and I must obey.

Birthday, Colditz

I look out of the castle windows and down upon the town. It is steeped in mist, there is a dampness, a chill in the air, and the wind blows a spatter of rain upon the glass. It is but little warmer in the room. There is no comfort here. I am a prisoner. I have been so for nearly five years. Five years. Can you understand what that means? Can you feel the monotony of summer after summer, winter after winter, walled up, shut away from life? The smell of the sea is in your nostrils, the sun shines down the valley. You can walk and walk and watch the plovers wheeling and hear the curlew call. There is a deep fire burning at home and the evening is quiet. All that is yours and much besides, to me they are just a memory. Here there is no joy - our world is grey and I am twenty-five today.

If that boy who years ago looked through the barbed wire at the Bavarian Alps and dreamed of Scottish hills could see the man who now gazes out upon the mist, would be recognize himself? I doubt it. In fact I think he would find a stranger with a hardness in his eyes.

I know that I have changed. An inevitable process. It is not possible to live thus long, continually fighting apathy, always improvising, often hungry, cut off - without being hammered into a new shape by the slow beat of time. That is the key-note. Slowness. A dull ache. A weary succession of movements.

Gradually I learned a little about the inconsistencies of human nature, and with the knowledge came tolerance. I learned too, the value of comradeship, and the worth of humour - that wonderful gift that for a fleeting moment seems to put everything into perspective. I can say that I have been cold and hungry, have lived in squalor, cramped and frustrated. I realize what freedom means.

And for such I have given my youth. I cannot know if the exchange has been a fair one. But I do know that despite all courage, a mature outlook and new found self-reliance, a man at times can feel desperately alone.