Curtis Culp knew hummingbirds were much stronger than their size would suggest.

For the past seven years, the Dunster resident has banded about 1,700 Rufous hummingbirds, but two weeks ago he received some surprising news.

One of the juvenile birds he banded last summer was reported in Foley, Alabama back in December - a distance of 3,621 kilometres covered in six months.

"It was a shock, for sure," Culp said.

Bird banding involves catching a bird, placing a metal band - like an ID bracelet - around their leg, and noting information such as age, sex, health and size. The bird is then released and the information about its habits can be tracked when another bird bander locates it.

Supported by the Canadian Wildlife Service's Bird Banding Office, the practice is one of the most useful techniques in the research and monitoring of migratory bird populations.

Culp and his wife Bonnie became involved with bird banding after an area group of birdwatchers were looking for someone to help track hummingbirds.

"A lot of them would end up on our porch," said Culp, who has a permit from the banding office since migratory birds are protected in Canada.

Before a permit is issued, the bird banding office verifies that the capture and marking method is appropriate for the species and that each bander has the necessary skills to handle the birds.

Culp said he tries to band birds in three minutes or less after catching them in a net that drops over their birdfeeder. He places the bird in a specially made wrap, cinches the band around its leg and checks and notes the length of the bill, the wing and if there are any parasites if there's time.

"The main is the stress of the bird. I don't like to stress them out," he said, adding he can tell by their eyes if a bird is in distress. At that point, he lets them go, whether or not he has all the information. "The main priority is bird health. As far as I know, I've never hurt a bird."

Prior to the Alabama find, the farthest Culp had heard of one of his birds making it was west Texas two years ago.

"It's quite interesting to see where they go," he said.

It's even more impressive considering hummingbirds don't travel like other birds.

"They don't go up and catch a strong airstream. They go flower to flower, feeder to feeder," said Culp, who bands about 200 to 300 birds every summer and has had about 20 return to his feeder.

"It's kind of like winning the lottery," said Culp, who enjoys the ability to give something back to nature by providing information on the species.

Beginning in May, Culp will get the first influx of birds and will be banding mostly males to start.

"The females are going to be nesting, so I don't want to mess with them too much," he said. Culp's permit also allows him to mark the birds with a dot of water-soluble paint on their back, which should make the birds easier to spot.

"I know these males must go through Prince George," he said, noting those with bird feeders can spot Culp's birds when they stop to feed.

"It's a lot of work, but it's interesting to do and show people," said Culp.

Photo cutlines:

Marked Rufous.jpg

Submitted photo

A female Rufous hummingbird with a leg band and a paint mark.

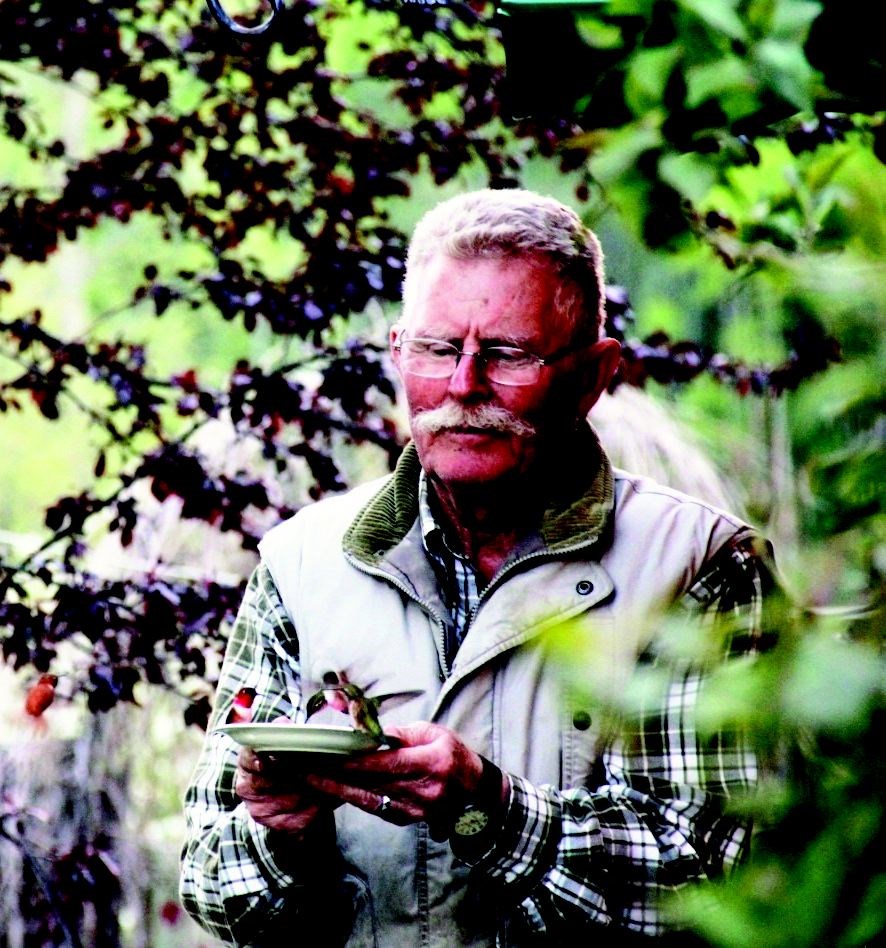

Curtis and hummers

Submitted photo

Retired farmer and volunteer bird bander Curtis Culp.