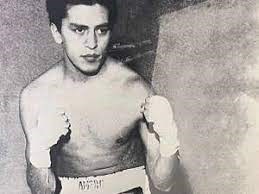

Roger Adolph, one of the most famous and successful fighters ever to come out of B.C., was not your typical boxer.

Dressed in a fringed buckskin robe his mother made for him at her home on the Fountain Indian Reserve (now known as Xaxli'p First Nation) near Lillooet, Adolph was a press agent’s dream when he made his pro boxing debut Feb. 27, 1967 in London, England. He lived in the East End and mimicked the Cockney accent, dressed in tailored suits, a bowler hat and umbrella and when he stepped through the ring for his first fight he was already on his way to becoming a fan favourite.

Known as Roger Threefeathers, the Fighting Red Indian Cockney, for 2 1/2 years, the Prince George Boxing Club alumni took on some of the toughest guys in the world. Soon as he got in the ring the crowds started bellowing Indian war whoops and Adolph responded, reeling off 13 consecutive wins in the featherweight (124-pound) class, compiling a 14-4 pro record.

He died on Oct. 31 at age 80 and former Prince George Citizen sports editor Doug Martin, a friend of Adolph’s for more than 60 years, said Adolph achievements in sports as a boxer and as a tireless Indigenous rights advocate are just part of his life’s legacy.

“He was the nicest guy in boxing,” said Martin, from his home in Powell River. “He did so many things. He spoke in front of the United Nations. He went and accepted the pope’s apologies for residential school abuses. He was a judge in Nicaragua on native subjects. He was a great fighter, a Canadian champion at 118 pounds and he turned pro and fought in the biggest venues in England.

Adolph had small hands and was never a knockout puncher. It was his exceptional fitness, strong legs and knowledge of the fight game that rocketed him to the top.

“He wasn’t a puncher, not particularly strong, he got by on technique, smarts and cardio,” said Martin.

Given the name Tmicwus by his grandmother at birth, Adolph might have gone to become a world champion in England but he got homesick and his mother lost her home in a fire. So he returned to Canada to answer the bell fighting for indigenous rights for his people.

In 1979, he moved back to his home near Lillooet and was arrested several times by federal fisheries officers for catching salmon out of season. One of his arrests resulted in the jail being surrounded by protesters who refused to leave until he was released.

Adolph was appointed chief of the Xaxli’p Nation, a position he held from 1982-2006, and was one of the central figures in negotiations to help his people establish land claim rights. He was one of the first chiefs in Canada to show support for the Mohawks in 1990 protesting a court decision that allowed a golf course to expand on their traditional territory in Oka, Que. As a show of solidarity and to try spur treaty negotiations, he set up rail and road blockades near Lillooet that closed the BC Rail main line, prompting a visit from B.C. premier Bill Vander Zalm. Adolph met with the premier wearing the traditional black face paint of a warrior. He never advocated violence but he stood up for his people.

Adolph was invited to the Vatican by Pope Benedict and on March 27, 2009 he joined other First Nation chiefs, residential school survivors, and church leaders in a 20-person delegation for a private mass in which the pope apologized for the abusive treatment of children and cultural genocide of the Canadian residential school system run by the Catholic church.

Adolph attended residential schools in Williams Lake and Kamloops, along with his siblings, and that’s where he got his start in boxing. He got involved in a fight during a basketball game and ended up joining the high school team in Kamloops. At 19, his career as an amateur bantamweight began to flourish when he took a job in Prince George in 1963 to work as a dispatcher for the Pacific Great Eastern (PGE) Railway. Adolph joined the Prince George Boxing Club, working with coach Harold Mann, the 1962 British and Commonwealth Games champion, and went on to win 54 of his 65 bouts over the next three years, bringing the 1963 Canadian bantamweight title back to Prince George. In those three years at the Prince George club, which later became Spruce Capital Boxing Club, he defeated the likes of Walter Henry, Jackie Burke, Billy McGrandle and Pete Gonzalez and training for those fights established Adolph’s work habits in the gym.

“When I face frustrations and want to quit, I remember my old coach (Mann) saying, ‘You’re only into the eighth round, you’ve got two more rounds to go,’” said Adolph, in a Dec. 7, 1973 Citizen article. “I was unsure before I came here but I gained a lot of friends and self-confidence.”

Discouraged after he was left of the national team heading to the 1963 Pan American Games in Brazil, Adolph quit boxing for six months, but resumed his amateur career in Prince George and fought for the next two years until he moved to Vancouver in 1965.

Seeing how successful he was, the Canadian Amateur Boxing Association promised Adolph a spot on the national team in 1967 but he already had his mind made up to turn pro in England. He had hopes of trying to develop young boxers and returning to England to be in their corner, watching them turn into world-class fighters.

“A top-notch Indian boy could really become an attraction over there,” he said in a Dec. 13, 1968 Canadian Press article. “I just wish all Indian people here knew how much they are looked up to in England and in the (European) continent. It would really make them proud.”

Martin said Adolph’s superior conditioning separated him from his boxing peers. In the fall of 1968 he proved what kind of engine he had when he decided to run the entire 90-mile route of the Moccasin Miles March from Vancouver to Hope nonstop to raise money for indigenous projects in B.C. He overslept that morning and started three hours after the rest of the participants and the next day finished his run well ahead of the rest of the field. The event was well-covered by local media and a radio announcer asked him, “What are the Indian people going to do with the money you raised?” Adolph’s sense of humour was revealed when he replied: “Buy guns, white man.”

Adolph was a family man and father of three who loved working with kids in the gym and he served as executive director of the B.C. Native Amateur Sports Federation, which he helped set up to encourage indigenous kids to pursue sports at high levels. He also spearheaded the Just Do It Sports Society to encourage leadership and participation in sports.

“Sports to the Indian people are natural, but there are very few Indian athletes of provincial prominence,” said Adolph. “Indians are slightly paranoid about the idea of competing in white society.

“I hate to see the old ways pass but they have to. Indians cannot float with the tide of events. They should try to make use of and understand the white culture without forgetting who they are and where they come from.”

Adolph was inducted into the B.C. Amateur Boxing Association Hall of Fame in 2012 and Martin suggests there should also be a place for his friend in the Prince George Sports Hall of Fame.

“He put Prince George on the map,” said Martin.