He thought his life would never change.

In and out of jail since he was a young man, Kenneth Brian Tylee did not know anything different.

Until a Gladue Report was written on his behalf giving Tylee a new outlook and a new lease on life.

"I never had a family," Tylee said.

"Remember when you're young and your parents come to your school to talk to the teacher and see how you're doing?

"I asked my foster parents if they would do that for me and they said no. So I asked my social worker why and they showed me a piece of paper explaining that a husband, wife and son were killed in a car accident.

"They said I was in the car too and that I survived. And that it was me. So, I was by myself most of my life."

Or so Tylee thought.

Suffering through addiction and regular run-ins with crime, Tylee lived in Vancouver for many years spending time in various correctional facilities including Burnaby and then eventually in Prince George.

"I didn't think I had a chance. I had a number of charges against me and I just wanted a lawyer who would fight for me. I said no to six lawyers before I actually got one that did do something for me. The others just said they could make a deal with me. I didn't want a deal. I wanted someone to actually fight for me," he said.

Tylee expected a sentence of at least 12 years in prison.

But because his lawyer insisted on providing the judge with a Gladue Report, Tylee was sentenced to nine months of house arrest.

"I couldn't believe it. I went off to live with my brother in Fort St. James. Nine months went by and I haven't turned back," Tylee said.

Tylee found out later in life that he did have a mother, father and six brothers.

There was no car accident.

"They lied to me all those years," Tylee said.

It was a happy ending for Tylee but for the many other aboriginal men and women in jail, a happy ending might not seem possible.

Aboriginal adults account for nearly one in four (24 per cent) of admissions to provincial correctional facilities in 2013/2014 and the numbers are steadily increasing.

"Over the last three years, we've seen a 30 per cent increase of indigenous incarceration," said Christina Draegen, northern regional manager of the Native Courtworker and Counselling Association of B.C.

"Gladue reports are rarely seen these days. I think it's a right of indigenous people that is effective when we can use it," Draegen said.

"The trouble is there isn't enough available funding to support it. Gladues are few and far between."

Gladue reports were introduced into the legal system to reduce overrepresentation of aboriginal peoples in prison and return offenders to their communities in an effort to turn their lives around.

The details about how to fully implement it, however, have never been planned and costed out.

The Gladue Report came to be as a result of a landmark 1999 Supreme Court decision from a 1995 case involving a young Cree woman, Jamie Tanis Gladue who was charged with murdering her common-law husband.

Her sentence was reduced based on certain factors which included living on a reserve in a city which wasn't in an Aboriginal community.

Judges have since been required to give special consideration when sentencing aboriginals based on their background in terms of: history, physical or sexual abuse, residential schools, child welfare removal or substance use.

"These days we see more Gladue components in court. These are limited and condensed, nothing like a full Gladue Report," said Draegen.

"It could be because of underfunding that we just don't see them. Resources are so limited today and this could be the reason why we don't see them. It could also be because there are just not enough Gladue writers who are trained. The reports are very time consuming when trying to get indigenous history, someone's history. And trying to reach some of these remote communities could be difficult also," Draegen said.

The Law Foundation of British Columbia is a non-profit foundation that receives and distributes the interest on funds held in lawyers' pooled trust accounts maintained in financial institutions.

It is this foundation that provides Gladue Report funding.

The average cost for a Gladue report is between $1,200 and $1,400, according to the foundation.

According to the Legal Services Society of B.C., Gladue reports can be 10-20 pages long and take eight weeks or longer to write.

The report tells the judge about one's history as well as strengths and where help is available to deal with issues brought before the court including personal goals. For Tylee, a Gladue report made all the difference.

"I was so used to jail. They lock you up, no one beats on you. It was home to me," Tylee said.

"Then when I found out I had a family, everything changed. I remember a lady who worked at the jail, she said she will exchange with me but with hugs. I was used to using my fists. That's when I realized that someone actually cared. I guess that's what I needed."

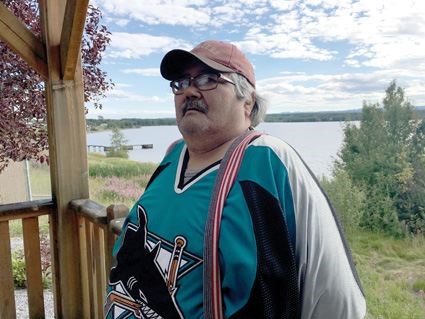

Since finishing his nine month house arrest, Tylee continued to live on the Nak'azdli Reserve in Fort St. James.

"I'm a member of the band, I sit on a couple committees and I have a dog now. I'm happy. I'm even in bed by 9 o'clock every night," he laughed.

"I don't know where I would be if it wasn't for Gladue. I'd probably be back in Vancouver doing the same thing I was doing."

The Legal Service Society of B.C. hopes to approach Ottawa with a plan for a common strategy by mid-winter.

Draegen still believes this "right" can make a big difference.

"The Gladue report is such a great tool but there are definitely challenges. The reports can make a huge difference for a judge in knowing things he would never have known about otherwise," Draegen said.

For Tylee, Gladue changed his life.

"I'm glad I'm here," Tylee says.

"It feels so good to be part of something."