Siloed, border-driven jurisdictional rules have made “criminals smile and families cry” for too long, according to Kevin Brosseau, now four months into his job as the commissioner of Canada’s fight against fentanyl.

But the tide is turning rapidly, he said in a June 17 speech to the Vancouver Anti-Corruption Institute’s 2025 Conference on Asset Forfeiture. Two weeks ago, Prime Minister Mark Carney’s Liberal government tabled Bill C-2, better known as the Strong Borders Act, a suite of measures that Brosseau said “tightens a financial noose around transnational organized crime.”

“You squeeze the side of a balloon on one side, it’s going to pop out on another. You focus on what happens at the border, it will impact on what happens on Main Street,” said Brosseau, who toured ground zero of Canada’s fentanyl crisis, the Downtown Eastside, with Vancouver Police officers on June 16.

Brosseau spent more than 20 years in the RCMP, with stops in Williams Lake, Burnaby and Beaver Creek, Yukon. He rose the ranks to become the top Mountie in Manitoba from 2012 to 2016 and then three years as the RCMP’s deputy commissioner. Harvard-educated in corporate and Indigenous law, Brosseau also held senior roles in Transport Canada and Department of Fisheries and Oceans before last October’s appointment as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s deputy national security and intelligence advisor.

Brosseau got a sudden, new assignment in the wake of President Donald Trump’s tariff-triggered demand that Canada get serious about battling the fentanyl crisis.

“Feb. 11 was a bit of an auspicious day for me, because it was not what I expected to happen that day,” Brosseau recalled. “As I was minding my own business, walking the halls of the Prime Minister's Office, ready to give advice on the latest national security issue and in conversations.”

Brosseau’s business card says “Canada’s Fentanyl Czar.” He admits it is a title that “my spouse and family roll their eyes about frequently,” but it carries high expectations.

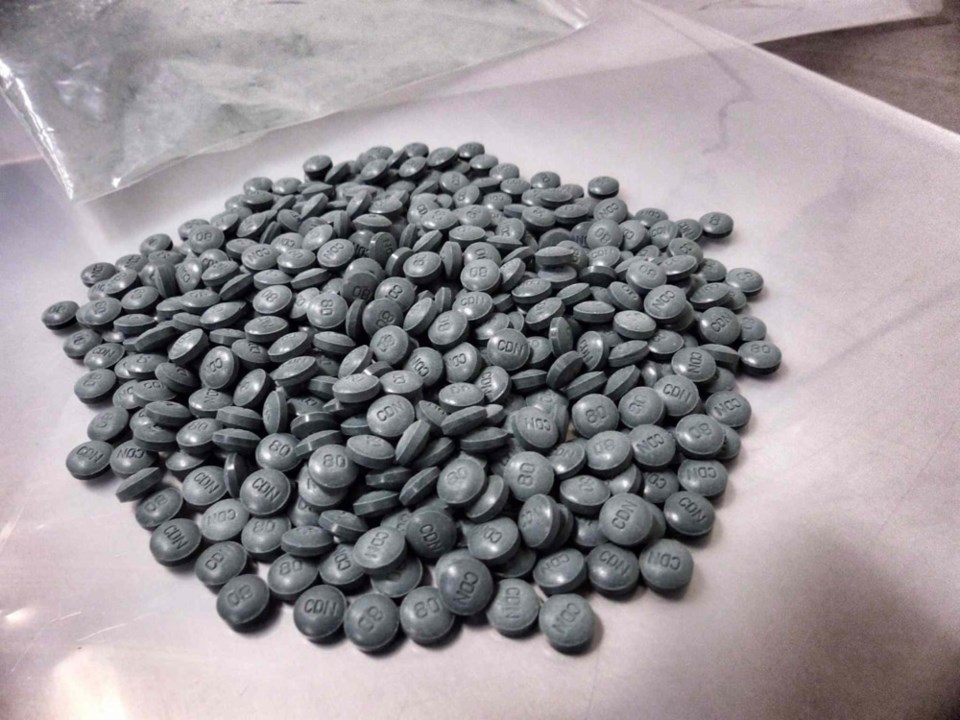

Fentanyl addiction and overdoses are not just a public health emergency, but a national security threat, he said. Synthetic drugs are now the largest criminal market in the country. It is not just about what comes in — such as precursor chemicals and finished product — but what gets sent abroad.

An average 21 Canadians a day lose their lives to synthetic opioids. Frontline workers, parents and grandparents now have “a sense of hope that somebody’s going to do something about it.”

It won’t be easy. While March was BC’s six-consecutive month of fewer than 160 deaths, Brosseau said small, remote communities around the country — especially Indigenous communities — are not seeing improvement.

The BC Centre for Disease Control reported 110 unregulated drug deaths in 2024 in the Prince George local health area, the highest in the Northern Interior, up from 100 in 2023.

In 2015, the year before the province declared a public health emergency, there were only 12 such deaths in Prince George.

Brosseau said political leaders at all levels of government and Canadians in general are “fed up” and want “all elements of public institutions and, frankly, civil society and corporations doing their part to right the wrong.”

To that end, criminal prosecutions and civil asset forfeiture need to work hand-in-hand.

“The hardest hits you can deal with to criminal organizations are made not only in cuffs and courtrooms, but they're made when you take their stuff away,” he said.

Take away their houses, cars and crypto wallets in civil court cases, “the things that make that world go around.”