Crime rates among young adults spike immediately after they reach drinking age, according to a new study by a Prince George researcher.

"Among people that are say 19 and one week and those that are 18 and 51 weeks, we see that dramatic jump," said Dr. Russ Callaghan, whose research team works out of the Northern Medical Program at UNBC.

"At a population level, it's quite significant."

Reported violent crime, like robbery and physical or sexual assault, increased by 14.9 per cent for women and 7.4 per cent for men. All crime increased by 10.4 per cent for women and 7.6 per cent for men.

Callaghan looked at national data over five years - 2009 to 2013 - pulling from all police-reported crimes. That means the reported incidents didn't necessarily lead to charges or convictions. The Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics anonymized the numbers, giving them in batches of weeks rather than exact birth dates. But that still allowed Callaghan to closely compare what happens as youth reach their province's legal age limits.

"They're very similar groups. They're only different on one thing though, one is released from a drinking age and one isn't," said Callaghan of the study, which was published August 30 in the international journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

Callaghan hopes his research, which previously looked at similar spikes in driving-related offences in connection with drinking age, will galvanize discussion around alcohol policy in B.C.

"I would hope the public would at least think about these laws," he said. "They've been in place for a long time and I know they're quite controversial."

The Canadian Public Health Association and a national expert-panel working group recently recommended the legal drinking age be raised to at least 19 years, with 21 years as the ideal. In Alberta, Manitoba and Quebec the legal drinking age is 18, while the rest of Canada sits at 19.

He's realistic, however, and recognizes raising the legal drinking age would be "quite unpalatable" to most people even if it would be the best evidence-based policy.

"There's always a balance between individual choice and the ideals of public health and we have to deal with that as researchers," Callaghan said.

At the very least, looking at these numbers, people should realize "alcohol isn't an ordinary commodity and that it carries harms associated with it, especially for young people," he said.

"Often we'll focus on the drugs which are much farther away from us like the illicit drugs like cocaine or opioids or fentanyl we'll make a big deal about those - and rightly so - but what we'll see if we take a closer look at alcohol-related harms is they're much broader and they're much bigger in our society."

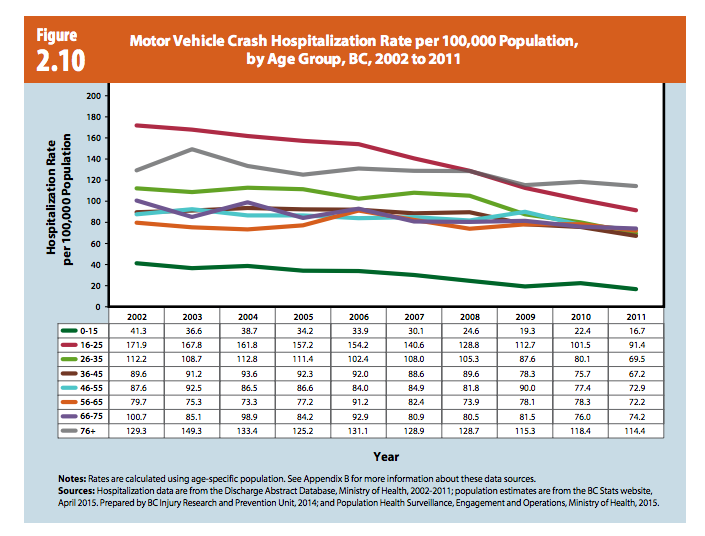

A March 2016 report by the Ministry of Health, Where The Rubber Meets The Road, offers a number of recommendations to address the high rates of motor vehicle fatalities and injury rates among youth, aged 16 to 25.

One suggested extending the zero blood alcohol rule for new drivers until they reach age 25, an option Callaghan finds interesting. He also pointed to price regulations around highly concentrated alcohol that is traditionally cheap - and popular among youth.

The marked jump among crimes committed by women struck Callaghan as interesting, because most research focuses on male criminal behaviour, unsurprisingly, because more crimes are perpetrated by men, he said.

"We do see that these particular laws do have an impact on female crimes as well. The research really hasn't looked at that very closely."

Callaghan is nearing the end of his series investigating the impact of alcohol-related legislation and said his next focus will look at its impacts on youth victims.