Long before it was considered important work, Wilson Duff devoted his life to understanding First Nations in British Columbia cultures and the impact of settler colonization.

As an anthropologist and UBC grad working for the B.C. Provincial Museum, Duff became an advocate for Indian rights and ownership who worked incessantly to expose white settlers to Indigenous perspectives. His knowledge of Indian people and their 25,000-year history as the original inhabitants of the province made him an expert witness on groundbreaking court cases that paved the way for land title claims.

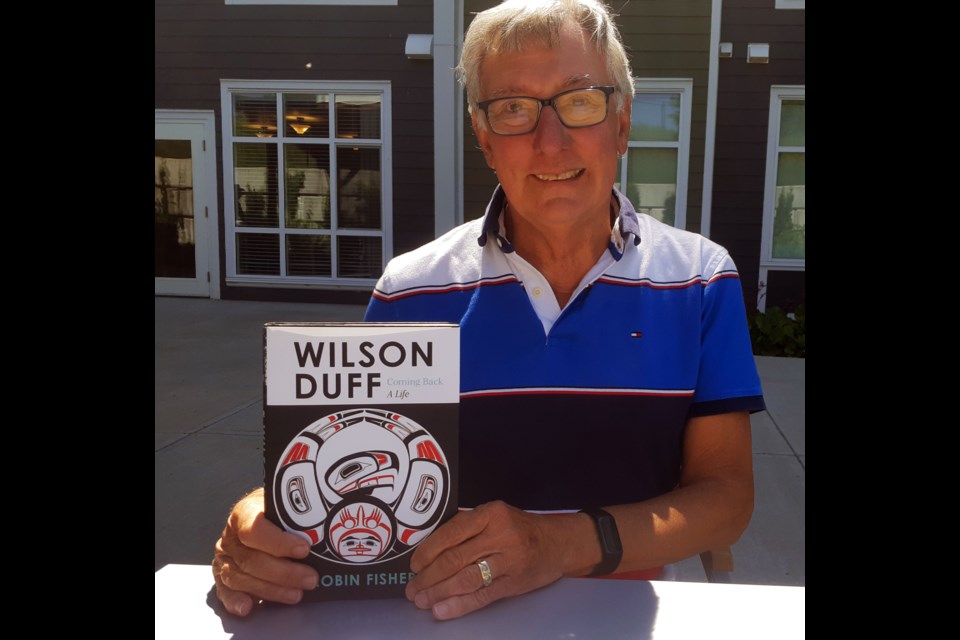

But much of his pioneering efforts to build bridges between First Nations people and white society was hidden until former UNBC professor Robin Fisher started digging into his past to research his biography, Wilson Duff: Coming Back, a Life.

“Starting in the 1950s, Wilson was doing all he could to understand First Nations cultures in British Columbia and then telling the newcomer settler society about that culture to bring some understanding between the two,” said Fisher. “So I think he’s important for history, but he’s also important for today because he was doing reconciliation and bringing First Nations people into the museum in the 1950s, and we tend to hear that these days as if it’s something new.”

Fisher, who moved to Prince George in 1993 to become the founding chair of the UNBC history department and the university’s first dean of arts and science, met Duff soon after arriving in Canada from his native New Zealand in 1970 for his doctoral studies in B.C. history at UBC. Duff was a UBC professor at the time who served on the supervisory committee overseeing Fisher’s three years of work as a PhD student and that began his five-decade devotion to learning about the province’s history and the impact of Europeans on First Nations cultures. Fisher’s book, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia 1774-1890, first published in 1977, is considered a definitive reference source still in use as a textbook at Canadian universities.

Fresh from his experience launching UNBC, Fisher was in Calgary to oversee the birth of another university as vice-president academic in 2009, the year Mount Royal College became Mount Royal University. A year later, he was introduced to Duff’s daughter Marnie, who asked him if he would be interested in writing about her father’s life and that set Fisher on a 10-year path to complete his latest book.

“I think Wilson has been a forgotten figure and what is known about him often was kind of academic gossip rather than reality,” said Fisher. “So both Marnie and myself wanted to write something that at least brought some accuracy to the story.”

Fisher’s first living source for his research was Barrhead, Alta. farmer Art Skirrow, then the only surviving member of Duff’s Royal Canadian Air Force bomber flight crew. Duff served as a navigator while they were stationed in India. Skirrow told Fisher that Duff was the smartest man he’d ever met.

Born in Vancouver in 1925, Duff served as the provincial anthropologist at the B.C. Provincial Museum (now Royal B.C. Museum) from 1950-65, until he was hired to teach history at UBC. He taught for 11 years and one of his anthropology courses proved hugely popular and led to him writing a book, Wilson Duff’s Indian History of British Columbia: The Impact of the White Man. Published in 1964, it was geared to all British Columbians and he said its intent was to help them understand the history and predicament of First Nations people.

“He was a very humble but compelling teacher and students found him very approachable,” said Fisher. “It kind of feels like he taught a whole generation of students about what’s going on in First Nations communities at a time when that wasn’t something most British Columbians were particularly interested in. It was a time when, basically, the newcomer population didn’t care and wasn’t listening.”

Duff was called as an expert witness in 1964 by B.C. Court of Appeal in Vancouver to testify in the White and Bob case. The two members of the Saalequun tribe on Vancouver Island near Nanaimo had been charged under the Game Act after they were caught with six deer carcasses hunted out of season. Convicted of the charges in 1963, the appeals court upheld an agreement made in 1854 between the Nanaimo tribes and the Hudson’s Bay Company for the right to hunt and fish for food in any unoccupied Crown land. It confirmed the existence of a treaty negotiated by Sir James Douglas and is the first Canadian case to consider the impacts of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, and it provided the legal framework for the development of Aboriginal rights.

Duff also testified in the Nisga’a court case of 1973, in which the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the rights of native people in the absence of a treaty, and that led to the creation of Canada’s land claims negotiation policy. Originally rejected by the Supreme Court of BC and Appeals Court, the later decision established Aboriginal title to their traditional, ancestral and unceded lands.

During the last eight years of his life, as a UBC faculty member, Duff concentrated on studying Haida art and interpreting the symbolic meanings behind the carvings, totem poles and painted crests that have become synonymous with the culture of coastal First Nations. In 1967, he partnered with esteemed Haida artist Bill Reid on the Arts of the Raven exhibit in Vancouver and also created the Images in Stone B.C. display of 1975, which went from Victoria to Vancouver and Ottawa.

“They were two very innovative exhibitions, both of which were driving at the view that northwest coast native art was great art in anyone’s terms, just as anything in the national gallery in Britain in great art,” said Fisher. “It’s not just ethnographic artifact, it’s actually great art with great thinking behind it.”

While he was working at the museum, Duff salvaged totem poles from Haida Gwaii which were showing the effects of decades of weathering and brought them to the Victoria museum to preserve them. That created controversy and was seen by some as illegal appropriation of artifacts but Duff was careful to negotiate permission and forward payment to the Skidegate band council before he took possession. Fisher said those poles, some of which were sent to the provincial museum and some of which ended up at Museum of Anthropology at UBC, will shortly be the only surviving examples of art surviving from that time period.

“When Wilson was taking totem poles from Haida Gwaii and getting them restored and preserved, there were articles in the Vancouver Sun with headlines like, ‘Hideous Totem Pole Nonsense,’ not that it was offensive to First Nations communities to remove these poles, but that it was waste of money and this was an artform not worth preserving,” said Fisher. “Wilson was doing these things not just when it wasn’t popular but there was pressure against it.”

Duff, who suffered from depression that might have stemmed from his war experience, committed suicide at age 51 in his UBC office in 1976, leaving behind his wife, son and daughter. He believed in reincarnation and that his life was simply the threshold to his next life. That spiritual transformation is depicted on the cover of Fisher’s book which reprints the Eagle Full Circle painting by Tofino-area artist Roy Henry Vickers. As a high school student from the Nass Valley north of Terrace, Vickers met Duff at the provincial museum and Duff dug into his office filing cabinet and showed him a photograph of Vickers’ grandfather. He credits Duff with inspiring him to become an artist.

Published by Harbour Publishing, Wilson Duff: Coming Back, A Life is available at Books and Company of Third Avenue and at Coles in Pine Centre Mall.

Fisher, 76, lives in Nanaimo with his wife Patricia and he continues to teach courses in First Nations history at Vancouver Island University’s Elder College.