Growing up on Nak’azdli Whut’en territory near Fort St. James with her parents and 11 siblings, Yvonne Pierreroy knew how to speak the Dakelh language long before she heard English spoken.

At an early age, her mother taught her the 46 sounds and double consonants unique to their language, and she had plenty of opportunity to learn how to make those sounds make sense.

Living off the land on Stuart Lake meant doing chores early on, and she grew up speaking her Dakelh ghuni language while working alongside her brothers and sisters picking berries, tanning hides, smoking meat and fixing fishing nets.

She didn’t realize it at the time, but she was preserving a language and culture that might otherwise be forgotten. For Pierreroy, that became her life’s ambition.

“The knowledge I carry comes from my parents — Mildred and Frank Martin — they were my teachers,” said Pierreroy. “I’ve always believed in the importance of sharing what I know with those who want to learn, so that Dakelh language and culture will continue into the future.”

Pierreroy always enjoyed school and learning new things, and it was while attending residential school from Grades 5 to 8 in Lejac that she started thinking about going to university to become a certified teacher.

She married soon after high school, and her responsibilities shifted to caring for her husband Ron and their son and daughter. She held on to the dream of earning a university degree, but it would have required two years of study at the College of New Caledonia and two more at UBC in Vancouver — a move she didn’t want to make with her family.

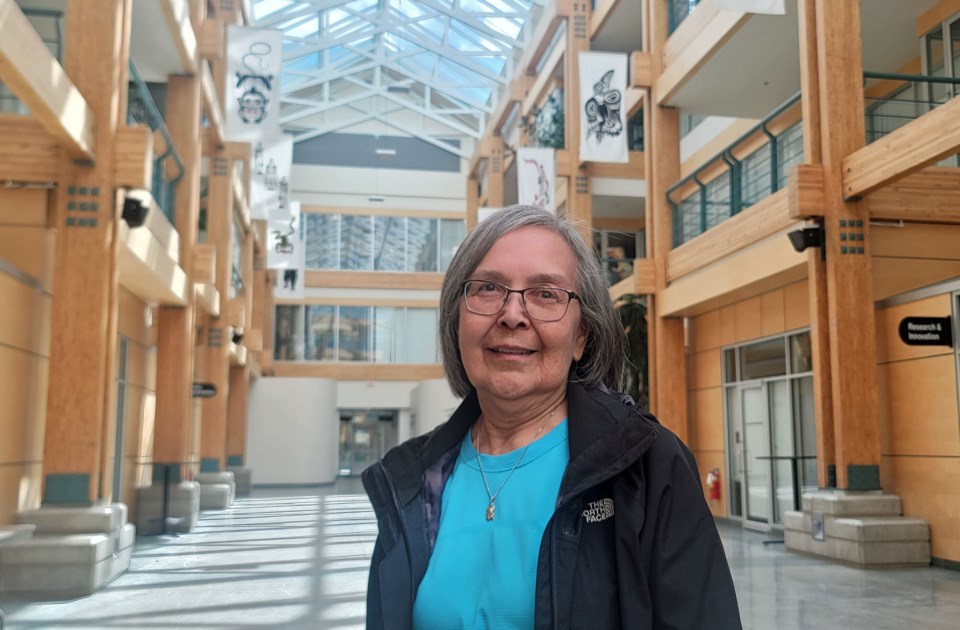

On Friday, May 30, at UNBC’s Brownridge Court, that dream will come true when the 71-year-old accepts her honorary doctor of laws degree.

It’s a reward for a lifetime of extraordinary efforts to preserve, revitalize and celebrate the Dakelh language — and a culture she vows will never be forgotten.

Pierreroy was the fourth-oldest of the 12 children in her family, with two older brothers and an older sister, each born two years apart, followed by seven younger siblings born about a year apart. Her father, Frank, was a paddlewheel boat builder with extended family living in villages along Stuart Lake. As soon as school was out for summer, they packed up the kids to visit relatives — and they all spoke Dakelh.

“My dad built a house right across the street from the high school in Fort St. James, but Indigenous people weren’t allowed to attend public school, so I was sent to Prince George for high school in Grade 9,” said Pierreroy. “It gave me new opportunities. Basically, I left home when I was 10. Even though we went away for school, my parents were so rich in their language and culture, we kept it up. All my family are culture and language teachers now.”

That includes eight surviving siblings, including Nak’azdli Whut’en hereditary Chief Marvin Martin, as well as cousins and nieces who still speak Dakelh. Her mother, Mildred, and older sister taught the language for decades in a private school.

“I’m still sharing my knowledge after all these years, and now this is my degree — I feel very honoured,” she said. “There are so many people to thank: my mentors, my parents, my husband, my two adult children, all my siblings, my late aunt Catherine, who I co-instructed with here at UNBC, my cousin Nellie Prince in Prince George — we developed some curriculum together and taught some courses in the community.”

Although difficult for adults to learn, she says Dakelh is gaining traction with a new generation of students now being exposed to it in elementary schools.

“My language and my culture is who I am, and it’s important because we’re losing more of it,” said Pierreroy. “In the school, we start when they’re in nursery and still at that age where they pick up the language fast. Our younger generation is very interested now, and when we educate the public on who we are, then they understand better where we came from.”

Hired on April 28, 1992 — two years before the university opened — Pierreroy was part of the first intake of employees at UNBC. She worked for 17 years in the provost’s office, played a role in hiring faculty and administration, and worked with the board of governors. During that time, operations were based out of downtown office buildings while the main campus on Cranbrook Hill was under construction.

In 1994, she enrolled in the first Carrier language course as part of the First Nations and Endangered Languages program. She was among the students from that inaugural class to suggest UNBC adopt the Dakelh Nak’azdli words “En Cha Huná” — meaning “respecting all forms of life” — as its motto.

Those words have become guiding principles for Pierreroy. UNBC has said she “has spent her life embodying the spirit of the motto through her deep respect for others, openness to diverse perspectives and passion for sharing knowledge.”

“When I started my employment with the university in 1992, I thought this is my opportunity to work and get a degree, so I started part-time studies,” said Pierreroy. “Five courses into it, I was asked to co-instruct the Dakelh Carrier language and culture course, so I put my dream aside. What I wanted to do was share my knowledge with students at the university, and here I am today — I am getting my degree.”

Pierreroy collaborated with UNBC and the Nak’azdli Whut’en Band Council to launch the Dakelh Language Certification Program in 2006. The initiative was designed to help Indigenous students transition from their home communities to academic life at UNBC. The program has since become a template for other First Nations learners preparing for university.

As a member of the Carrier Linguistic Society, Pierreroy worked with other speakers to revise the Dakelh dictionary and produced books, recordings, digital tools and online platforms to keep Dakelh traditions and culture alive. She also wrote a user-friendly, interactive Nak’azdli phrasebook for medical students and healthcare professionals to help them communicate with Dakelh-speaking patients.

A Dahelh elder, Pierreroy is also known as a gifted artisan, using her skills in beadwork to create clan vests, wedding mukluks and button blankets.

“Teaching others how to bead or make moccasins is about more than crafting — it’s about connecting to culture in a hands-on way,” she said. “Every stitch holds meaning, and when I share those skills, it’s another way to pass on knowledge in a meaningful way.”

She credits her strong family upbringing for giving her the foundation to succeed as a well-educated academic dedicated to teaching and preserving the traditions that define her culture.

“I’ve never done this work alone,” said Pierreroy. “My 97-year-old mother, Mildred Martin, has always been beside me, as was my late father Frank — passing on knowledge and guiding me. My husband Ron has supported and worked with me every step of the way. We’ve always worked in tandem, and I’m grateful for their strength, love and commitment to our culture.”

UNBC president Geoff Payne said Pierreroy’s 35-year connection to the university and her dedication to the First Nations and Endangered Languages program make her a natural choice to be honoured at the May 30 graduation ceremony.

“It was a way to recognize everything she’s done to accomplish her dream, and we’re happy we can do this and really highlight the amazing person she is and the contributions she’s made,” said Payne.

“It’s about leading the way and people following her — seeing what you can accomplish and being a beacon for the next generation,” he said. “When you think about where the university is in terms of truth and reconciliation, and trying to embody all the things Yvonne has spent her life advocating for — she’s absolutely the perfect person to receive an honorary degree from UNBC.”