How many of us can speak the languages of the people on whose traditional territory we live in? That’s the question posed by Our Living Languages: First Peoples’ Voices, a new exhibit being hosted by the Fort St. John Museum until September.

Dane-Zaa, Cree, Tse'Khene, and Dene K’e are just a few of the languages spoken by Treaty 8 nations from the Northern Rockies down into the Peace Region.

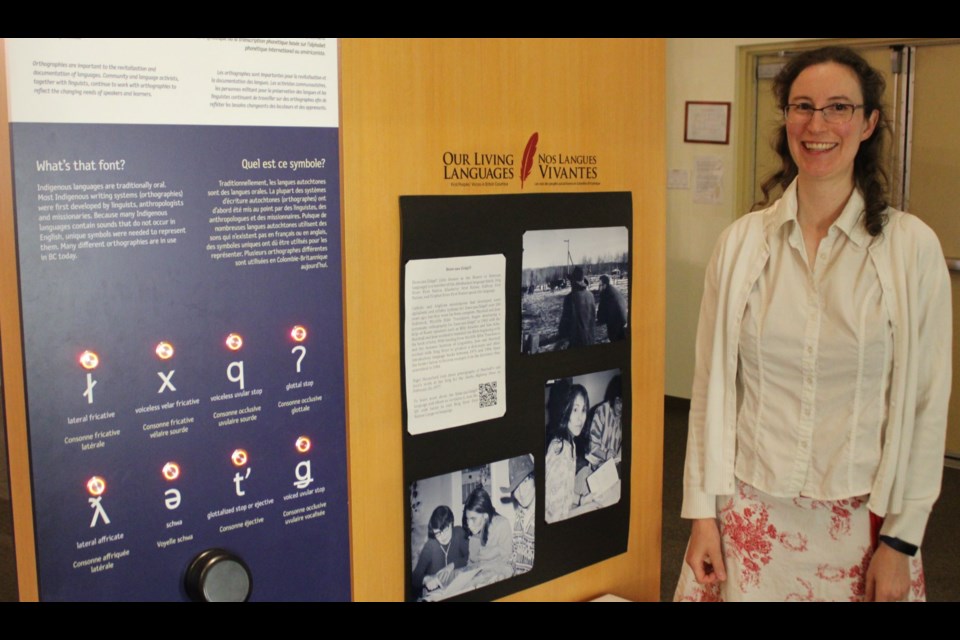

Many indigenous languages have gone extinct or are considered "sleeping" due to the scarcity of speakers. However, Fort St. John museum curator Heather Sjoblom says the exhibit is one of hope, with indigenous languages be revitalized across the province.

“It’s a really great way to learn about languages across B.C.,” she said. “Some of it is depressing because it explains how the languages were lost, but it’s a hopeful exhibit because there are people working to revitalize it, for the 34 languages that aren’t sleeping.”

Since 1890, indigenous languages and speakers have declined rapidly, largely due to the impacts of colonialism. Settlers brought diseases like smallpox, which killed large numbers of indigenous people, while others were forbidden from speaking their language when taken away to residential schools.

The exhibit includes an interactive map that breaks down First Nations by traditional territory and the number of speakers in each distinct region of B.C. Audio samples of the languages are also included for visitors to listen to.

Sjoblom further localized the exhibit, providing a panel about fluent Dane-Zaa speakers Billy Attachie and Sam Acko from Doig River.

Starting in 1962, Attachie and Acko worked side by side with bible translators Marshall and Jean Holdstock to produce a Beaver language dictionary, titled Dane-zaa Zaaage. Working through the 1970s, the dictionary was completed in 1984.

Doig River First Nations has since put the dictionary online, in addition to several other linguistic guides and learning tools to encourage people to speak and write the Beaver language.

Today, just 12% of speakers are fluent in Dane-Zaa or the Beaver language; 66.3% do not speak their traditional language, while 21.6% understand or can speak a little. Another 16.1% are learning the language.

“That’s the cool part, there is a fair amount of people learning it,” said Sjoblom.

Cree, the most widely spoken First Nations language in Canada with 83,000 speakers, faces a similar issue – only two per cent are fluent while 95.3% do not speak the language at all. However, 2.9% are learning, and only 2.7% understand or can speak a little.

Our Living Languages: First Peoples’ Voices is on display at the Fort St. John North Peace Museum until Sept. 5.

Tom Summer, Alaska Highway News, Local Journalism Initiative.

Got a story or opinion? Email Tom at [email protected]