CONTENT WARNING: This story includes content regarding “Canada’s” ongoing genocidal epidemic of MMIWG+. Please look after your spirit and read with care.

To get my daughter to school on the Snuneymuxw First Nation, we must pass by the Nanaimo Regional Landfill. We drive by and witness our Eagle kin as they compete with vultures and crows for scraps of food. I often ponder how many other First Nations in “Canada” are situated right next to municipal garbage dumps.

Up until recently, we lived on the reserve close to this landfill. My daughter, her father and her siblings are all Snuneymuxw citizens. During the summer months, the heat moves the rancid scent from the dump over the cedar trees, spilling over onto my sacred children and their ancestral homelands as they play in the yard.

We recently moved off of the reserve and into the city of “Nanaimo.” I drive by the dump now more than ever, as that’s the route to and from my kids’ school. Just before a school drop off one hectic morning, I read a headline about the alleged serial murders of four Indigenous women in “Winnipeg.” The remains of one of the women was found at the Brady Road landfill. The bodies of two others are believed to be at the Prairie Green landfill. Disposed of, like garbage, in a man-made wasteland. As it often does when hearing about my kin in the news, my heart sank. I was able to carry on only by going into survival mode — of focusing on the responsibilities of being a mother, getting my child to school on time, dutifully hiding my emotions to remain positive for her sake.

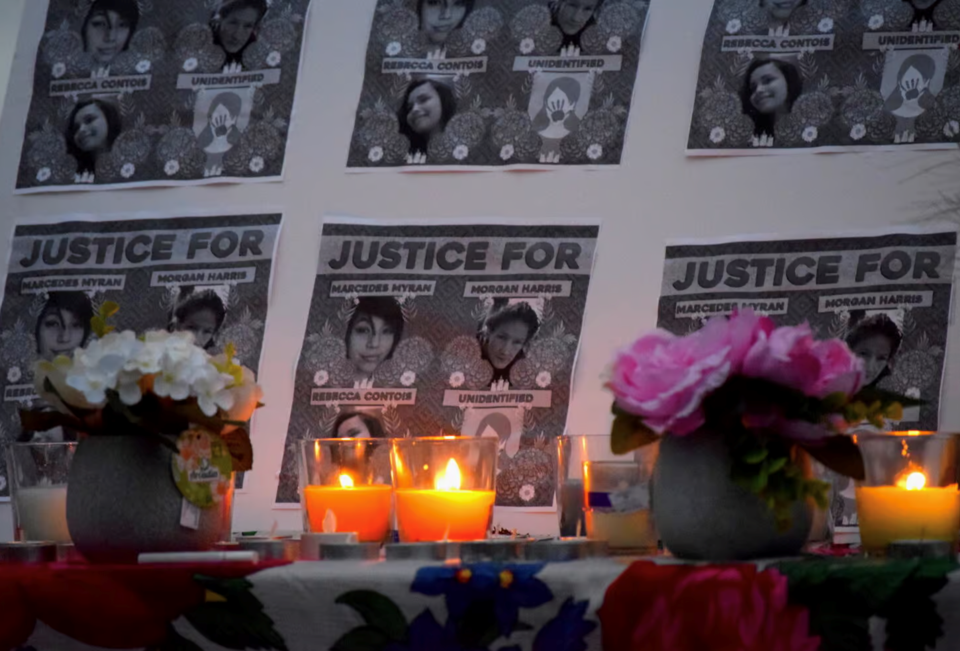

Later that day, I stopped to sit by the river and scan the news and social media for more information. Rebecca Contois, Morgan Harris, and Marcedes Myran were the known names. There was also a woman found who no one has been able to identify. Elders and knowledge keepers named her Mashkode Bizhiki’ikwe (Buffalo Woman). I watched the river, which was abnormally high from the rain. I thought of fifteen year old Tina Fontaine and her lifeless body floating down the river in a blanket after being discarded, her murderer walking freely.

I know I am not the only one haunted by our missing and murdered women and girls.

This hit close to home for me, as a Cree woman who has many relatives and kin in “Winnipeg.” I recently spent a week there in the summer, exploring playgrounds, outdoor spaces, and restaurants with my daughter and father, as we made our way to visit our homelands. I had a private moment on the shores of our ancestral waters in Opaskwayak, paying homage to the life of Helen Betty Osborne, who was murdered in my home territory in 1971.

The men who abducted and murdered her were never charged.

Her name was Linda Mary Beardy

I initially started writing this piece to channel my grief and rage in December. As the shock and horror dissipated from the media, as it always does, I put this particular story aside.

Then, this week, news broke of another Indigenous woman’s body found at the Brady Road landfill. Her name was Linda Mary Beardy.

In a statement from her family, they say that Linda was a mother of four children, a sister, auntie, niece, cousin and friend. She was 33 years old. Her remains were found in the same area as Rebecca Contois.

“We remember Linda as a super devoted auntie, who always stepped in to play and had such a contagious laugh that filled any room she was in,” reads the statement.

Beardy was found by staff at the Brady Road landfill on Monday, April 3. Winnipeg Police have called her death “suspicious.” Today, Winnipeg Police Chief Danny Smyth says Beardy climbed on her own into a garbage bin, and that there is “no evidence to support homicide.”

Her untimely death comes during the one year anniversary of the death of Tatyanna Harrison, an Indigenous woman whose body was found at a marina in “Richmond.” It also comes during a week where many of our displaced kin on “Vancouver’s” Downtown Eastside (DTES) were forcibly removed by the Vancouver Police Department.

Sheila Poorman, the mother of Chelsea Poorman who was found deceased in the backyard of an affluent neighbourhood in “Vancouver” last year, was one of the last people to stay behind, making sure people were safe during the “street sweep.” Police came to a similar conclusion about her daughter Chelsea, suggesting Poorman had climbed the fence into the backyard on her own.

‘Indigenous women are simply not a priority’

Last week, the federal government released its budget for 2023. In response, the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) released a press statement calling the budget a failure.

“Year after year, the budgets have been consistently disappointing. With words but no actions, this government continues to show Canadians that Indigenous women simply are not a priority,” says NWAC CEO Lynne Groulx.

“Budget 2023 has failed to make it a top priority to protect and empower Indigenous women, girls and gender-diverse people.

“We wanted to see investments rooted in the principles of reconciliation and empowerment — and a commitment to Indigenous people taking our full place in Canadian society through significant investments in Indigenous reconciliation efforts that directly impact the well-being of Indigenous women.”

The release further details what little action has taken place to implement the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, which issued its final report in 2019.

During it’s release, the report was overshadowed by controversy surrounding its use of the term genocide, which has since been used by Pope Francis during his summer apology tour.

The final MMIWG report released a supplementary legal analysis on genocide, which says that the three intense years of its mandate unveiled “the existence of a genocide perpetrated by the Canadian state against Indigenous peoples.”

Amongst a heap of other impossibly difficult and violent realities, the MMIWGT2S+ issue is beyond a crisis. It is “Canada’s” shame. It is a constant reminder that women and girls who look like me don’t matter. I am reminded of the grief each time I pass the Nanaimo landfill. I want a world where my Indigenous daughters don’t read headlines about their kin being so violently discarded.

I’m not sure what else needs to be done for “Canada” to disrupt its deep rooted lethal romanticization of Indigenous women and girls that empowers folks to believe we are disposable. Thousands upon thousands of Indigenous women’s bodies have been violated and discarded.

The reality of what this country has allowed is like the rancid scent of the garbage dump, cascading over the cedars to assault our senses. Every “Canadian” should be outraged.