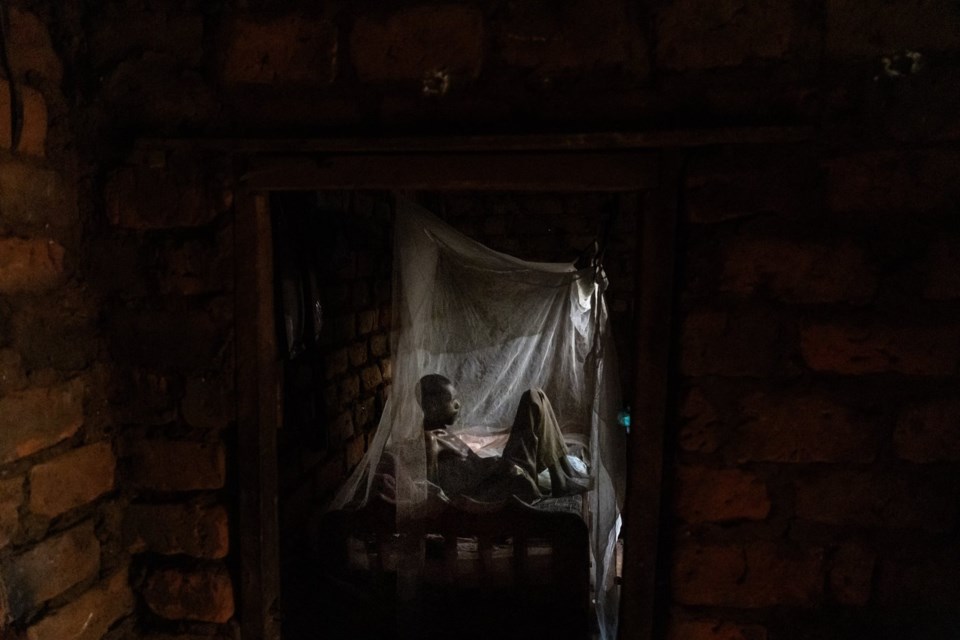

NKULAGIRIRE, Uganda (AP) — Past a smoldering pile of trash and two bleating goats, through a doorway beginning to buckle beneath the weight of the bricks above, is a darkened room where a skeletal, 70-year-old man lies on a pillowless bed above a floor littered with trash.

The lone window’s shutters are closed but enough shards of sun make it through holes in the corroded roof to see Joseph Malagho’s ribs poke at the skin of his torso and legs like twigs inside his olive green pants. As he struggles to sit up, leaves crinkle beneath him on a soiled sheet. His mattress sags. The air is thick and stale.

Malagho has no illusions about the difficulty of growing old. But the fact that he is here at all is its own miracle.

Across Africa, millions who once faced the death sentence of an HIV infection have survived only to face something nearly as daunting: old age.

As infections have dropped markedly and antiretroviral drugs have reduced mortality, the turnaround of the AIDS crisis has helped build Africa’s longevity revolution. Lives that were expected to be cut short instead continued decades more, changing the demographics of those facing the disease and fueling the rush of people encountering health systems that were never built for old age.

Malagho isn’t sure when he was infected, but he was diagnosed about five years ago. His health has steadily declined since. He has tuberculosis now, too, and can barely stand.

He hasn’t left this room in months.

There is barely any soap for his wife to wash him with a rag. His lone source of entertainment, a small radio, has gone dead, and there’s no money for batteries. He has lost most of his teeth and can’t afford dentures, but there is little food to eat anyway.

“If there is food or not,” he says, “I don’t even care.”

He urinates into a small white bucket and his wife hurls it outside just as the first drops of rain begin to strafe the roof and start leaking to the space below.

Reach One Touch One sponsors Malagho and has dispatched a field worker, Grace Nabanoba, to check on him this day.

The organization distributes food and medicine to many of its beneficiaries and helps repair homes, install water tanks and provide basic items, like a bed for seniors who are sleeping on dirt floors. But there are limits to what it can do and Nabanoba feels helpless as she stands before Malagho.

She promises him batteries for his radio and exits the home. Sometimes, after visiting him, colleagues will ask her why she’s quiet and she’ll slink off to cry.

“Some situations,” she says, “are too hard to bear.”

___

Matt Sedensky can be reached at [email protected] and https://x.com/sedensky

Matt Sedensky, The Associated Press