Sparked in good measure by the disproportionate number of Indigenous people in B.C.'s jails and prisons, an ambitious plan to create a separate justice system for First Nations is in the works.

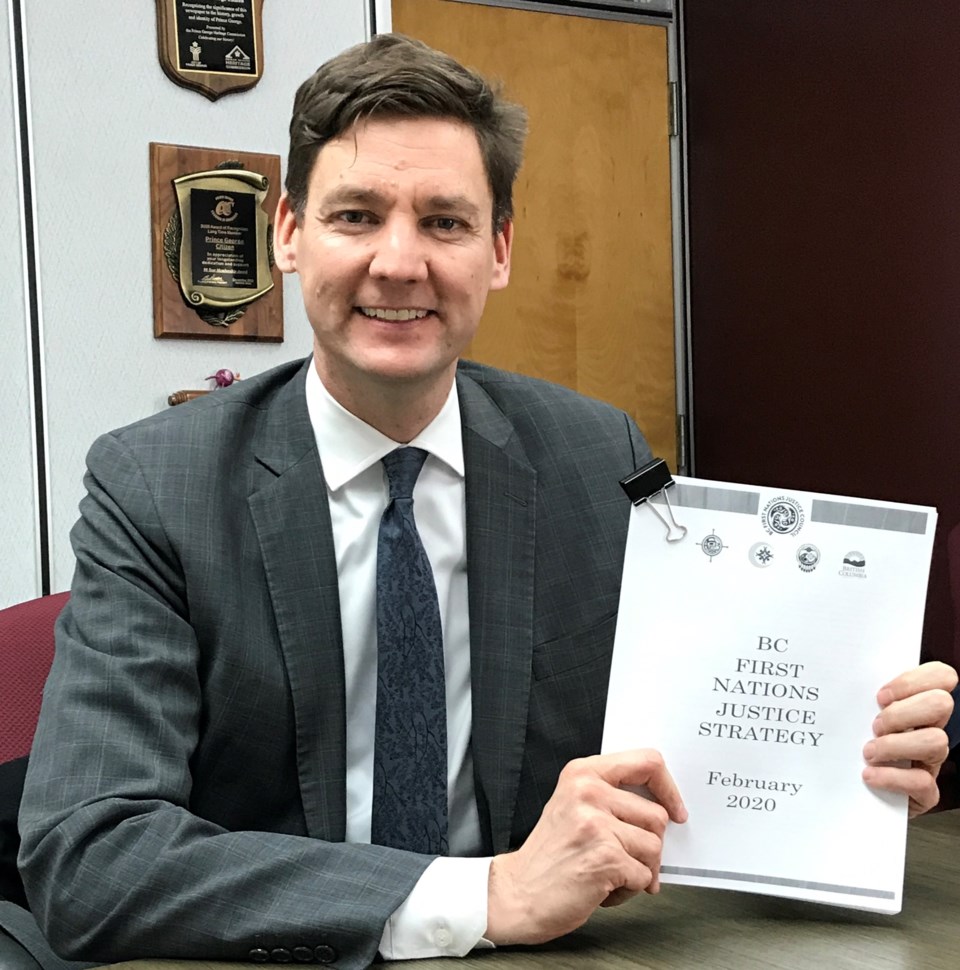

Unveiled earlier this month, the First Nations Justice Strategy is the "first strategy for Indigenous people that is actually written by Indigenous people," B.C. Attorney General David Eby said during an interview with the Citizen while in Prince George this week.

Produced over the course of two years, it sets out a wide-ranging course of actions aimed at reducing the number of Indigenous people in custody by giving First Nations significantly-greater control over how disputes are handled and offenders are treated.

In 2017-18, Indigenous adults and youth accounted for roughly 30 per cent of B.C.'s in-custody population, up from about 20 per cent a decade before, while making up just six per cent of the province's population.

"The way that the system is going is not sustainable," Eby said. "We can't just keep locking up more and more Indigenous people and hope that things are going to change because they're not, they're getting worse.

"This is a way to try to do things differently and respond to that crisis that we face and hopefully provide some support for these communities to try and turn themselves around."

Key among the strategy's actions is a call to advance First Nations "self-determination of justice systems and institutions" and falling from that, development of First Nations courts.

There are six Indigenous courts in B.C., including one in Prince George that is held in provincial court once a month. While they are more culturally-appropriate than the mainstream version, the strategy effectively calls for a separately-run system of courts where First Nations laws and jurisdictions are applied through First Nations courts.

If that sounds dramatic, said Eby, one need look no further than Washington State to see a example of what the strategy is talking about.

"They have a very developed justice system that is run by and for Indigenous people in that state," he said. "People of a particular Tribe, as is the American terminology, can opt into their own justice systems that are run by their own Tribe.

"They aren't more lenient but they are more responsive to cultural realities. So they're going to have someone judging them who is a member of their own Tribe, a member of their own community, and for some people that makes a significant difference."

Other actions in the strategy include increasing the number of so-called Gladue writers in the spirit of the 1999 Supreme Court of Canada decision on R v Gladue. It requires judges to consider an Indigenous offender's background in crafting a sentence and that, in turn, often requires a report written by someone trained in compiling them.

It also calls for increasing the representation of Indigenous people on the other side of the justice system in the form of judges and Crown prosecutors. Just five of B.C.'s 150 provincial court judges are Indigenous and of the roughly 460 prosecutors in B.C., no more than five identify as First Nations.

For those serving sentences, expanding culturally-based programs at correctional centres is also a goal, as is developing a network of corrections alternatives within First Nations. B.C. Corrections is also working with some First Nations to develop the supports to successfully reintegrate members back into their communities once they have been released from custody.

Next steps include establishment of three Indigenous Justice Centres to provide "wrap-around" services related to legal help and support. Exactly what will be offered will differ between communities and depend on what services are already in place, "but for starters, it'll be a lawyer, a legal worker, advocates to support people who are involved in the justice system."

The communities where they will be set up are to be announced before the fiscal year ends but "Prince George would be a totally appropriate location," Eby said.

Many of the goals in the strategy have been described as aspirational and are contingent on the federal government stepping up to the plate. However, Eby said Ottawa has place a big priority on the issue and during a recent meeting B.C.'s strategy was presented to federal and provincial justice ministers.

"Our piece fits in very nicely with what the feds are trying to do," he said.

The full strategy is posted with this story at www.princegeorgecitizen.com.