Team Nunavut has come farther than any other team to the Canada Winter Games in Prince George. Yes, Newfoundland and Labrador is farther from this city than they are to Central Europe, but the northernmost territory's team had to travel all the way south before they could travel all the way west.

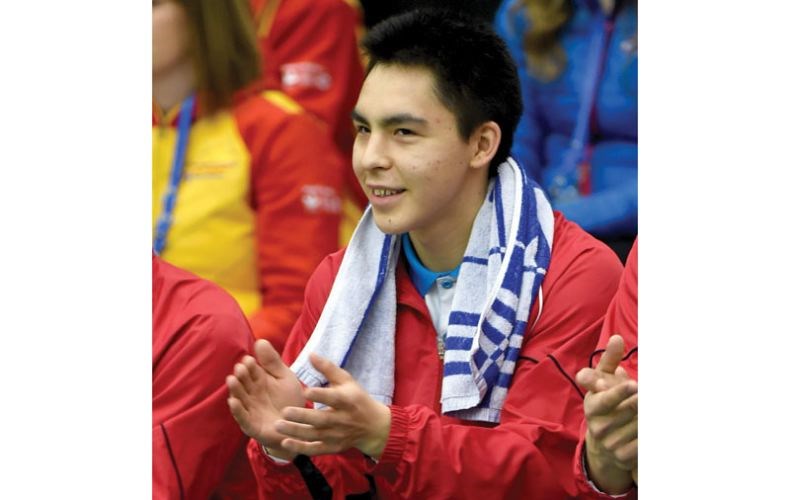

And there is the matter of Jayko Akeeagok.

The 18-year-old badminton player lives in Grise Fiord. It is the most northerly civilian community in Canada and indeed one of few such locales in the world. It's Inuktitut name is Aujuittuq, meaning "the place that never thaws."

Akeeagok sleeps in a bed that is just as close to the north pole as it is to Nunavut's capital of Iqaluit, let alone the rest of the country. The only way into Grise Fiord is by the annual ship that brings supplies, or by Twin Otter that only the most experienced bush pilots are allowed to fly, so complex is the airfield there.

It was that Twin Otter that first took Akeeagok out of his home community on the journey to the Games. He had to change to a second plane before he arrived in Iqaluit to rendez-vous with his fellow Nunavut teammates, then a jet to Ottawa, another to Vancouver. This took five days, followed by the hop up to Prince George.

"Home is a really small community: One hundred-fifty people. I know everybody. Everybody," he said. "They are really proud of me. They kept wishing me luck."

More than that, even since he's been gone, a lot of youth and some adults too have taken up badminton back in Grise Fiord, according to Nunavut's chef de mission Mariele DePeuter.

"It's because of Jayko," DePeuter said. "It is driving up our numbers for badminton players, so that's good, but it also just gets kids into the gym, people being active. That will translate eventually into better living like it does anywhere else, but it will help the whole high-performance end of our mandate in Nunavut too. Some of those athletes will maybe not stick with badminton but still pursue sports."

Akeeagok doesn't consider himself a role model, but he does consider himself a leader. It says so on his title. He is in Grade 12 by day but at night he helps operate the new village multipurpose gym. When he was training for previous events like the Territorial Games (gold medalist in 2011), all he had to work with was a gym big enough for a single badminton court. Now he and those he plays with have modern facilities that put them at least on equal footing with their competitors to the south.

And all their competitors are to the south.

Akeeagok has no specialized coach in Grise Fiord either. His mom got him into the sport in about 2009. He won early matches that built his motivation. He has come south a couple of times for intensive training at the Vancouver Racket Club - the whole 10 days prior to these Games, the Nunavut squad gathered there to learn and build up to this event - but then he is on his own again back home.

He isn't the only one in this position. Nunavut's curling skip Sadie Pinksen said she and her teen rink "are part of leagues in Iqaluit so we get games in, but they are mostly adults, and they aren't there to coach us. It's hard to get comparable competition because it is so expensive to travel anywhere in Nunavut."

Most people their age are focused on hockey or soccer, she said, so curling makes the four of them an oddity.

Jonah Oolayou, 21, and Brittany Masson, 20, have an easier time finding peer competition being based on the badminton courts of Iqaluit, but they agreed that high-level coaching was lacking in virtually every sport.

"It is important for our athletes to get out to events like (the Canada Winter Games) so they can bring the experience back to Nunavut to expand our sport," Masson said. "We (in the Nunavut uniform) are trying to get around to other sports to cheer on all our athletes. We need to be there for each other, because our fans can't come as easily like other provinces."

"Being here at the Games is great for building relationships with other provinces too," said Oolayou, who is now turning over university choices in his mind, and B.C. is high on the list based on the training he's received at the Vancouver Racket Club. "Whatever happens, I want to end up back home. I want to bring whatever I learn back to Nunavut."

"Our biggest challenge is just the logistics of getting everyone to one place," said DePeuter, who is also head of sports and recreation programs for the territorial government. "We came here with realistic goals - it is building blocks for us. These competitions are training opportunities and relationship opportunities. It is a stepping stone for the Arctic Winter Games, and we are seeing some of our athletes becoming medal threats. Whenever we go home from events like this, we advance our expectations a little more."

Even if those expectations have to travel more than five days almost to the very top of the world.

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)