Storytelling is, I believe, a great act of civilization. We share stories socially, we write them down, we speak them out loud. It's part of how we make sense of ourselves. The humanity of storytelling includes understanding how and when one story fits into another story.

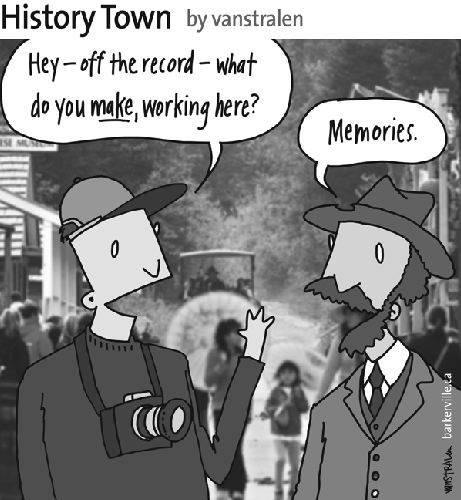

This week I was helping a new street interpreter wrestle with the challenge of Barkerville's signature 'town tour' - perhaps the most complicated, abstract show I've ever been involved during my career as a museum theatre specialist. We talked about the reasoning behind which stories are included and/or excluded from the formal presentation. There are so many Cariboo stories, and stories within stories, and we simply cannot cover them all in a single hour. Instead, we find ourselves having to cut stories we love because of time restraints, or relevance, or because a particular topic is being dealt with adequately by a different interpretive program. There are also situations, I said, when a story "just has to wait for its moment." She seemed a little confused by this last utterance, and for good reason. It can be tricky to grasp the idea that, sometimes, a story needs to wait for just the right time and place to be told.

Here is an example of what I mean: in 2013 the film Twelve Years a Slave was released. A cinematic interpretation of a true story from the 1850s depicting the highly charged history of American slavery, the movie went on to win an Academy Award for Best Picture.

British Columbia has its own, fascinating story that directly relates to the film's theme. In 1858, several hundred African-American families left California, where they had lived under legislated discrimination, for the Colony of Vancouver Island. British Columbia's first colonial Governor, James Douglas (who was himself the son of a free-born Creole woman) assured these new immigrants that they would be subject to the same laws as every other free citizen of BC, as well as the same basic rights and liberties.

Some of those 'citizens of colour' made their way to the Cariboo goldfields. Two of them - Wellington Delaney Moses (a barber) and Dr. William Allen Jones (a dentist) - are prominently featured in Barkerville's main street museum displays.

For many years, it felt awkward to find words to interpret this chapter of our colonial history. We have many wonderful American visitors to Barkerville every year, and we certainly do not want our story of acceptance to seem smug or self-righteous or purposely highlighted. We had to ask ourselves: "extreme historical significance notwithstanding, how does this story enhance the overriding narrative arc of the town tour?"

If we interpret this specific story of emancipation, how much additional information about Victorian racial tensions and the dawning age of multiculturalism introduced by Western gold rushes do we need to fill in to create context for its inclusion? Does the story fit this moment in interpretive history?

With the world-wide release and success of Twelve Years a Slave, an international discussion about slavery was reinvigorated. Consequently, in 2014, interpreting BC's small but significant chapter in this weighty North American story feels relevant, topical, and part of an important global conversation.

The opposite, however, can also be true. We might purposely alter or even exclude a story or theme due to current international events. The mythology of North America's gold rush era, for example, is steeped in images of guns and frontier justice. Visitors to Barkerville are often interested to know how weapons were carried, and controlled (or not) by lawmakers. The topic of weaponry has often been discussed in entertaining, sometimes even lighthearted, ways that self-consciously 'wink' at the Hollywood-style stereotypes many of us have come to recognize as emblematic of the 'Wild West.'

But as we began the 2014 Barkerville season, the media was fraught with stories of random shootings and other acts of violence - some of them as startlingly close to us as Vancouver. It may seem over-sensitive on our part, but when these world events are recent and raw it really does affect the way we interpret their historical antecedents. We try to be sensitive to the emotional, political and historical climate in which we tell our stories. We have to be. We may not even realize we are doing it, but our perception of historical anecdotes is unconsciously steered by modern affairs.

I am fascinated by the idea of a post-colonial Canada wherein we are beginning to see crucial, albeit difficult examinations of our nation's history relating to Truth and Reconciliation with our indigenous peoples (perhaps it is worth mentioning here that despite my rather Eurocentric appearance my great-great-grandmother was Khah-my of the Swxw7mesh[Squamish] Nation). I hope the idea of reconciliation leads to more interpretation of aboriginal themes in Barkerville.

Sometimes we won't tell a story if we do not feel we are, by our own comprehension at least, ready to talk about it. In this present-day moment of national reflection we are inching towards a time of greater understanding of a complex story that we need to tell in our interpretive venues... but only when the time is right. Although we certainly haven't avoided discussion of Barkerville's aboriginal history, nor the history of American slavery, we have been careful with any stories that require reasonable sensitivity toward, and careful consideration of, a culture that might not be perceived of as our own.