Millions of dollars were spent upgrading Lakeland sawmill's capabilities for processing beetle-killed pine but little work was done to handle the growing amount of explosive dust that came with the trees, WorkSafeBC says in a report into the causes of the fatal explosion and fire.

It was one of a list of preventable problems, according to the report made public this week, that led to the April 23, 2012 explosion and fire that killed two workers and injured 22 others, leaving some with severe burns and others with ongoing physical, cognitive and psychological trauma.

Investigators concluded the explosion's ignition source was a gear reducer for a five-horsepower motor used to power a waste conveyor in the northeast corner of the mill's basement, directly below the log transfer deck for the slasher saws.

It's believed the gear-reducer's fan had come loose and became embedded in the steel screen covering that end of the assembly, grinding into it and coming to a stop. The shaft continued to spin at 1,750 revolutions per minute and the consequent friction raised the assembly's temperature to 577 C, well above the 410 to 430 C needed to ignite a cloud of wood dust. And since the fan was no longer turning, "the fine dust in the air could freely migrate into this immediate area, even within the shroud," the report says.

In reaching that conclusion, investigators found there was no regular inspection or maintenance for the gear reducers. "The shrouds on some of the reducers were found to be clogged with oily sawdust, and the fans were damaged, loose, or missing," the report adds.

Adding to the trouble, the faulty gear reducer was located in an area reported to be one of the dustiest in the sawmill, yet where no wood dust collection system had been put in place.

The mill's waste management system was originally designed for green wood where about 14 per cent of the volume would become wood waste and dust, but as a greater amount of dry, brittle beetle-killed pine was added to the mix, the waste rose to as much as 36 per cent - well above the level the system could handle.

In the rush to process as much beetle-killed pine as possible, which carried a significantly lower stumpage rate than for other types of species, Lakeland had ramped up production and, in the same month as the Babine explosion, put a new lumber sorting system into operation that allowed it to cut wood with different moisture content at the same time.

But it did not have a waste conveyor system.

"As a result, a large amount of wood waste built up during an operating shift, which needed to be physically removed from beneath the new lumber sorter line," the report says.

An additional cleanup person was added to each shift a month later but the dust from the pine logs was difficult to handle. In contrast to dust from the green timber, it was so fine that it would simply blow away if shoveled onto a conveyor while it was moving.

Even so, the heat from the gear reducer could have resulted in a fire but not an explosion if not for the fact it was also located in a relatively contained area. It violently struck the under-floor of the operating level and travelled through the immediate basement areas, "lofting dust into the air and generating more fuel" that led to an even more violent secondary explosion and fire that destroyed the mill.

Two workers, supervisor Alan Little, 43, and large headrig operator Glenn Roche, were killed.

The explosion occurred at 9:37 p.m., while the crews were on lunchbreak, and Little would usually be in the mill office at that time to review the shift's production levels. Unfortunately, the office was located where most of the explosion pressure vented from the basement level.

Roche, meanwhile, had likely remained at the large headrig, about 60 feet north of where the explosion started. According to co-workers, Roche had become very focused on keeping the large headrig as dust free as possible - two previous dust-related fires at the location are documented in the report - and he routinely blew the equipment down with an air hose whenever he had a scheduled break.

However, when air is used to blow wood dust from equipment, the settled dust is disturbed and dispersed into the atmosphere in a cloud. As the explosion's subsequent fireball vented through the mill's openings, including those around the headrig, the dust cloud "would have been a fuel source and would have ignited instantly," the report says.

A further 22 workers were injured as the explosion travelled east to west through the operating level and collapsed the main lunchroom walls. Workers in the basement-level millwright's lunchroom were blown out through the south wall by the force of the explosion.

In early February 2012, two weeks after a similar explosion and fire had ripped through the Babine Forest Products sawmill near Burns Lake, a Lakeland employee anonymously called WorkSafeBC to say he was concerned about excessive dust buildup.

In a subsequent WorkSafeBC inspection report, the officer found the airborne concentration appeared to be below exposure limits but noted accumulation of wood dust in various areas of the mill and told management it should not be allowed to build up and create a hazard. No violation orders were issued.

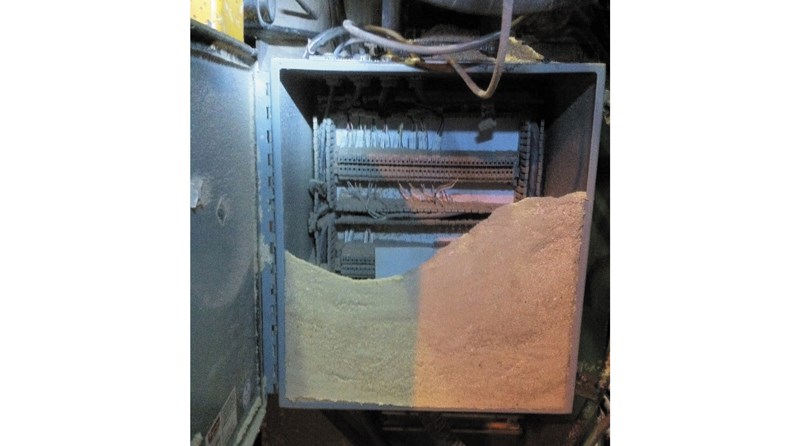

Lakeland was looking into buying a waste vacuum system at the time, and just 11 days before the explosion a sales rep or a supplier had visited the sawmill. He took photographs of several spots where there had been significant dust build-up, "including some areas in which equipment was completely coated with a very fine powdery dust."

He told WorkSafeBC he expressed concern about the risk of explosion but no others who were on the tour corroborated his statement. However, other workers told WorkSafeBC that the dust levels were excessive. One described the mill's east end "as being covered in 'fine, fine, fine dust and it was like walking on flour.'"

"He stated that they used squeegees to push this dust into the chainways," the report continues. "If there was any air movement or if the conveyors were running, the dust would just fly up in the air."

By then the mill's doors has been closed for the winter to preserve heat and the misting systems are also typically turned off to prevent freezing. But a gate that permitted air flow through the baghouse, part of the mill's dust collection system, was tripped so there was no air recirculating, making the system less effective.

Three days before the explosion, a maintenance worker was asked to check the baghouse for rips and other problems as a result of the high volume of fine wood dust. No trouble was found but the abort gate to return air from the baghouses back into the mill remained tripped.