Regardless of whether the B.C. NDP government decides to finish or cancel Site C dam, proponents of geothermal power are now hopeful that at least one small demonstration project may move forward.

They hope that it will prove that geothermal energy can be developed in B.C. for a reasonable price, despite the costly failures of the past.

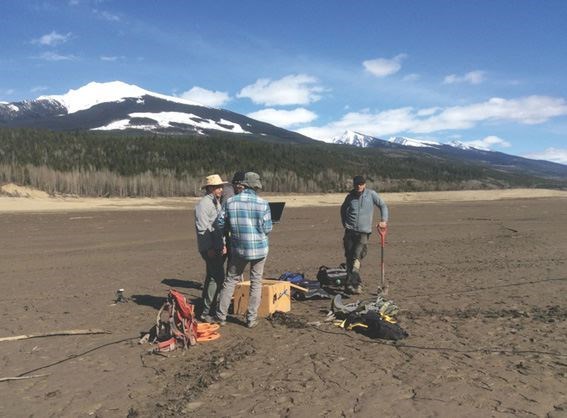

The project is near Valemount, just outside of Mount Robson Provincial Park. It was recently the subject of "raging agreement" in the legislature, where all three parties voiced support for the project.

The one holdup has been a drilling permit, which is still awaiting cabinet approval.

Once that is granted, Borealis GeoPower would drill a test well to determine the energy potential of a hot aquifer at Canoe Reach near Valemount.

The first phase of a three-phase project would be hot springs that the Valemount Geothermal Society wants to develop.

The second phase would be a small power plant that would produce one megawatt (MW) of electricity - nearly enough to supply the town of Valemount (population 1,100). The third phase would be a larger, 15-MW power plant.

Alison Thompson, CEO of Borealis GeoPower and managing director of the Canadian Geothermal Energy Association (CanGEA), said she thinks the drilling permit will be approved by cabinet.

"The permit is no longer the issue, but it took so long to get it, it made us miss an historic opportunity with the BCUC [BC Utilities Commission] to show everybody that this stuff is there and it works," she said.

She referred to the BCUC review of the Site C dam project.

Had a permit been issued earlier, Thompson said, an initial well could have already been drilled, which would have provided critical information on things like temperature and well flows that would have confirmed the geothermal energy potential of the Valemount project.

B.C. is known to have good geothermal power potential, since it is situated on the so-called Pacific Ring of Fire. In areas with volcanic activity, magma from the earth's core can rise close to the surface, heating aquifers to temperatures of 200 C. When tapped, the water can be hot enough to drive steam turbines to produce power.

Although geothermal power is more expensive to develop than wind or solar, it has one significant advantage over other renewables: it can produce consistent power around the clock.

It is a proven technology that has been used in Iceland for years, and B.C. has the geography for it. It also can have secondary uses.

Since it uses hot water and steam to drive turbines, it can be tapped to heat buildings or greenhouses.

And as John Burba, president of Colorado-based Ptech Chemical Consulting, told Business in Vancouver earlier this year, some of the hot brine aquifers that have geothermal potential might also be used to extract lithium, now a hot commodity thanks to demand for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles.

But all previous attempts to develop geothermal power in B.C. have been expensive flops. It can cost $4 million to $10 million to drill a geothermal well. And if the resource doesn't have the right temperature and flow, it's not likely to become a viable electricity producer.

As Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources Minister Michelle Mungall noted earlier this month, when grilled by BC Green Party Leader Andrew Weaver on the lack of progress on the Valemount project, developers spent roughly $25 million drilling a series of wells at the Meager Creek site, only to conclude that the aquifers did not have adequate flows.

"The result was that there was just not enough steam or water to move into full electrical production," Mungall told Weaver, in response to his criticisms that BC Hydro has never pursued any exploration of B.C.'s geothermal resources.

"I wanted to make sure that the member was aware that actually that work has been done by BC Hydro," Mungall said. "I should also mention that further work has been attempted since then in that site, yet with the same result."

Meager Creek has been something of an albatross around CanGEA's neck.

"I think what you have here is one project that's sticking out like a sore thumb - Meager Creek," said Thompson, who has an MBA and a master's degree in engineering. "It was a project that was ahead of its time. Technology today could probably get that project to produce."

She said new binary-cycle plants, which can draw power from reservoirs that are cooler than those used for other types of geothermal plants, can improve the energy-generating potential of geothermal wells. She added that Meager Creek's location was a problem, since it was too far from a population centre, which would require transmission lines to be built, adding to the project's capital costs.

"While it may be the hottest place in Canada - and I believe that today's technology could make it work - the economics may still not make sense because of its location."

The Borealis project at Valemount is closer to potential users of heat and electricity.

"We have several local businesses who are willing to buy geothermal heat and stop using propane, which is being trucked in," Thompson said.

The Valemount project is one of two geothermal developments that Borealis is trying to get off the ground in B.C. The other is Kitselas Geothermal Inc., a joint venture between Borealis and the Kitselas First Nation in Terrace.

The Terrace project is estimated to have a capacity of 25 MW, although BC Hydro's standing-offer program finances only projects of 15 MW or under.

Once the company has a permit, Borealis hopes to have holes drilled in the first quarter of 2018.