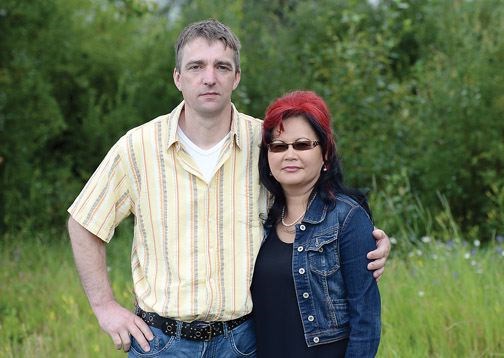

BURNS LAKE - Though Kathleen Weissbach doesn't understand German, she can tell when her husband speaks to family back home about surviving the January 2012 explosion that flattened the Burns Lake sawmill.

"I knew exactly when he was talking about the mill explosion because his legs and his arms would just start shaking," said Kathleen of Dirk Weissbach, one of 19 who lived through the Babine Forest Products disaster.

Just minutes before the 8 p.m. blast tore the roof off, Dirk was relieved from break by Robert Luggi, who died that night. His other co-worker Carl Charlie was the second victim, and the two are the focus of the coroner's inquest that started this week in the small town of about 2,000 people.

The 49-year-old's years-long recovery was difficult for the both of them.

In the beginning, because Kathleen was thrust in the position of caregiver for Dirk, who suffered four broken ribs, a broken collarbone, a concussion, back trauma, and second degree burns to his face, neck and ear.

"It was a whole role reversal," she said, adding the road to recovery was long after he emerged from three days of induced coma.

She still remembers the night sweats that soaked the sheet so thoroughly that she'd thought Dirk had wet the bed. She helped him go to the bathroom, bathe and drive him to every appointment.

"Your life is in chaos," Kathleen said. "We've had so many different levels of normal. The first normal was coming home and acknowledging all of his injuries, PTSD and everything. Then you learn to live with that."

Often, she said, the affects of trauma on the families of victims is forgotten.

"It was like pushing a wheelbarrow full of cement. You just have to keep on going," she said, adding it helped living in Francois Lake where they were separated from the grief in Burns lake. "It was something we talked about, but it wasn't something that we dwelled on."

Dirk has learned to shut the memories of the flattened mill out of his mind, the cries for help and the heavy smell of smoke.

Often in the evenings, right around the time the mill exploded, he'll get a sick feeling in his gut.

"It was just good luck I found a hole in the wall," he said of making his way out of the mill, despite the destroyed exits and the building in tatters around him.

"I'm not sad nor do I linger in pity for myself but it is something I must deal with every day," he wrote in an update to family.

While he still suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder ("it never goes away"), the memories don't plague him like they once did.

And Dirk doesn't dwell on injuries, despite their nagging presence when he carries weight or when his back relapses after too much effort. Money is always a stress and more than three years later, he's still looking for work.

"I didn't know it would be this hard," said Dirk, who is trained as a millwright, machinist and managed a plant in Germany for seven years before he emigrated to Canada just over 10 years ago. This month Kathleen will start working again part-time as a health assistant, but for the last few years her job has been helping Dirk heal.

"You feel guilty," he said of unemployment, especially since he'd been working since he was 16.

But those stresses don't compare to the anger he feels knowing no one will be held accountable for his co-workers' deaths.

"The toughest part is the injustice," Dirk said.

Before the blast the mill, owned by Hampton Affiliates, had become a frustrating place to work, he said, one where he felt safety wasn't a priority so much as production.

That January night, the temperature dropped below 40 degrees.

"It was pretty senseless to run this place in this kind of weather."

"They've got so many injuries and so many stuff happened," said Dirk, in reference to a fire in an electrical panel the year before. Most importantly, he said, it was so cold all water was frozen to cool the equipment and in the sprinkler system. "How can you run a place without fire protection?

"It's against the law to run it like this but we didn't know."

Dirk, like most of the families, wanted a public inquiry. The inquest creates an environment where no one takes responsibility, he said.

"It's a no blame system. They can talk all day, they can talk all year but nothing comes out," said Dirk, who was there for the first day, but said he'll likely stay away because it bothers him too much.

"It's closure for the case not for the families," he said. "You're still in rage and I think it never will stop."

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated the amount Dirk Weissbach receives in wage loss payments, his current benefit status and who relieved him from his break the night of the Burns Lake mill explosion.