B.C.'s north has a critical shortage of physiotherapists, say health advocates, underscoring a reality faced by many rural and remote communities in Canada.

Only 3.3 per cent of the province's physiotherapists work in the Northern Health region, despite it making up about seven per cent of B.C.'s population.

The region, which takes up almost two thirds of the province's land mass, has three times fewer physical therapists for its population compared to access in the rest of the province, according to 2014 data from the Physiotherapists Association of B.C.

"The crisis in a deficit of physiotherapists requires a growth strategy," said the PABC in an August 2014 report.

Two years later it was before the health standing committee in Prince George with the same message.

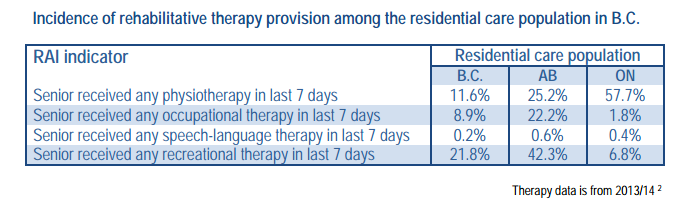

Nine northern towns don't have publicly-funded physiotherapy and three have unfilled positions, the committee heard. Less than two per cent of residents in northern care facilities get physical therapy, compared to 11.6 per cent in B.C., the worst in the country PABC said.

"Our concern is that rural British Columbians have particularly limited access to physiotherapy care," said Kevin Evans, the association's CEO.

"A wave of rural physios is retiring and not being replaced as new graduates flock to the Lower Mainland and private practice," added Hilary Crowley.

Crowley also works with PABC and is a member of the newly-formed Physiotherapists for Northern Communities with fellow physiotherapy advocates Terry Fedorkiw and Angela Rocca, who spoke on the same issue to the standing committee on finance in September 2015.

"Northern Health recognizes that physiotherapy is a challenging occupation to recruit to," said an email statement.

The health authority said it has recruited four new physiotherapists since May and that some tactics to recruit include sending emails to staff about its employee referral program incentive, reaching out to universities and instructors, posting jobs on its website and HealthMatchBC.

About 30 per cent of B.C. physiotherapists are over the age of 50 and 10 per cent are over 60. In the north, those numbers sit at 18 and 8.6 per cent respectively. Crowley said about 30 physiotherapists retire each year in the province, but only 80 students graduate annually in B.C.

In 2014, however, B.C.'s attrition rate was 59, Fedorkiw said.

Lack of access and poor coordination of rehabilitation services has become a "significant problem" for remote residents across the country, wrote the Canadian Physiotherapy Association (CPA) in a June letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

"We are making a concerted effort right now to look at rural and remote access," said Kate O'Connor, director of practice and policy at CPA, noting these communities are characterized by a higher prevalence of chronic diseases and traumatic injuries, higher rates of obesity, lower life expectancy, and fewer healthcare resources.

"B.C. (advocates are) doing a phenomenal job bringing this issue to the forefront because I believe it is only going to get worse."

Nationally, only one per cent of physiotherapists are classified as looking for jobs, often representing those in transition between positions.

"We really have to think about if we have 100 per cent employment rate, it will be quite difficult to address the immediate need so we have to look at the plan," said O'Connor, especially in remote areas. That could include more training positions, tele-health and better use of physiotherapy assistants.

Canadian demand continues to outpace the supply of physiotherapists, though that has seen steady improvement with 20,842 registered, according to the 2014 numbers from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

The supply of registered physiotherapists in Canada grew by about 14 per cent between 2010 and 2014, according to CIHI, data which doesn't include the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

Yukon and British Columbia have consistently had the highest rates of physiotherapists for their populations over the past five years.

Numbers have inched up in the north over the last year; the College of Physical Therapists of B.C. reported 104 registered as of July 26 this year, compared to 86 in 2014.

"Our goal is to get physiotherapy services equal to the rest of the province," said Fedorkiw, an advocate for a northern program at the University of Northern B.C.

In 2014, PABC found 267 job vacancies province-wide. This year, Fedorkiw said the Ministry of Health put the number around 167.

She doesn't see that as a sign of improvement.

"They likely underestimate the need because unfilled positions get eliminated," said Fedorkiw, an approach O'Connor said she sees across the country.

"If positions aren't filled, they are closed and funding is spent elsewhere."

For example, in northern B.C. nine towns don't have publicly funded physiotherapy because there are no positions, Evans told the health committee in July. They are: Chetwynd, Hudson's Hope, Tumbler Ridge, Mackenzie, McBride, Valemount, Atlin, Dease Lake and Stewart.

A further three have unfilled positions: Haida Gwaii, Vanderhoof (which also covers Fraser Lake and Ft. St. James) and Fort Nelson, which has a vacancy as of August. Some physiotherapists are overextended, the presenters said, with McBride also including the whole Robson Valley. For a time, Vanderhoof was filled by a graduating student after it had been vacant for seven years, Fedorkiw said.

Meanwhile, Northern Health said it has just six unfilled postings: three in Prince George, one in Prince Rupert, one in Fort St. John and one in Queen Charlotte City.

Telehealth is one solution, which has been used in some remote communities, like Yekooche and Takla, north of Fort St. James, Crowley told the committee.

Increasing university seats is key, argue advocates. The University of B.C. has the only physical therapist program in the province with 80 new spots annually, 20 of which are set aside for the rural and northern cohort.

"UBC has the lowest number of seats to population ratio amongst all of the provinces," Elizabeth MacRitchie told the health committee in Prince George, before advocating for more positions for northern physiotherapy students.

"If we've learned one thing about health care recruitment, it's this axiom: Train in the north, treat in the north," added Crowley.

On Saturday, The Citizen looks at the efforts to bring more training north.