Repercussions from one of this region's darkest moments in history are still being felt today.

In 1864, the combined nations of the Tsilhqot'in aboriginal coalition rose up to confront colonial settlers interloping on their lands west of modern day 100 Mile House and Williams Lake. The Tsilhqot'in forces attacked a road construction crew, a pack train and an additional settler. Nineteen colonials were killed.

On the pretense of peace talks, six chiefs of the Tsilhqot'in nations were called to a meeting in Quesnel. Instead of negotiations, the local leaders were arrested and hanged as criminals despite the killings being an act of war under the laws of the day.

The presiding judge was one Matthew Baillie Begbie.

The hangings were in contravention of the rules of military engagement. The colonial forces were not then in jurisdictional control of that region and modern court rulings have upheld that in many ways the same situation applies today, since no treaty or ceding of territory has happened over those aboriginal nations.

The day of the hangings has became a day of national mourning for the Tsilhqot'in people and the guilt of the crime lingered through British Columbia's history.

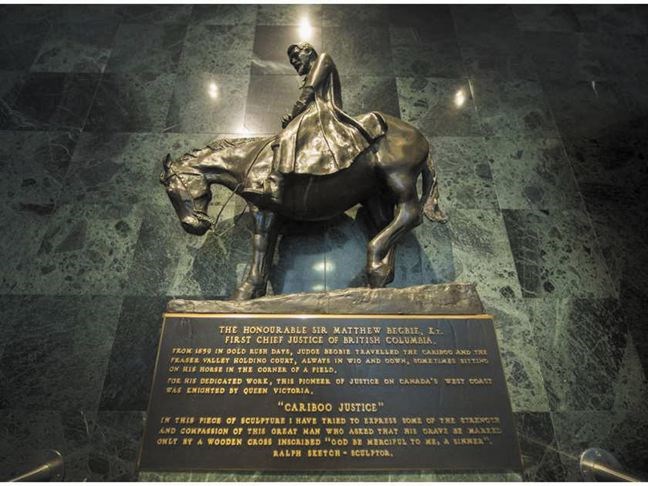

This past week, the Law Society of British Columbia took a step towards reconciliation with the province's aboriginal nations by removing the statue of Begbie from the lobby of its headquarters in Vancouver.

"We are listening to the concerns of the indigenous community and taking them to heart," said law society president Herman Van Ommen. "This is an important step in our journey toward reconciliation with indigenous peoples in British Columbia."

One of the leaders of the movement to remove the statue is an acclaimed lawyer himself and an aboriginal leader from north-central British Columbia.

Ed John is the Grand Chief of the Summit of First Nations. He is a former provincial cabinet minister and was distinguished in that position by having been appointed to the position while not a Member of the Legislative Assembly. John is a former co-chair of the North American Indigenous Peoples' Caucus and was one of the architects of the United Nations Declaration On The Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

John, also named Akile Ch'oh, is a hereditary chief of the Tl'azt'en Nation and was raised at Tachie, near Fort St. James.

Begbie was named the first judge of the new colony of British Columbia in 1858. Begbie was head of the courts when B.C. and Vancouver Island officially merged in 1870. And it was Begbie named as the first chief justice of the Province of British Columbia when it joined Canadian confederation in 1871.

Begbie was, from the time of his arrival until he died on June 11, 1894, a constant resident of B.C. and chiseled a reputation as a staunch upholder of fair rights under British-Canadian law. He is a figure of considerable cultural sway, in British Columbia, especially for his legal exploits while stationed in the bustling city of Barkerville during that tumultuous time. The hanging of the Tsilhqot'in chiefs in Quesnel, however, is a smear on his reputation despite it being murder by committee, not solely his action.

John was pleased with the gesture by the law society to remove the Begbie statue but called it only one step on the path towards social balance.

"It is a small decision but a very important one for the Tsilhqot'in people and indigenous peoples," said John, who today is co-chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Advisory Committee. "We have a large amount of work to do. It is our responsibility to make sure that law students and the legal profession understand the truth and the history, and that they can be a part of reconciling the relationship with indigenous peoples."

The law society made the promise in spring and this past week, only days from the anniversary of Begbie's death, they made good on it.

For the Tsilhqot'in National Government, it is only the first of what they hope is a total striking of Begbie from heroic references in popular culture.

"In 2014 the B.C. premier stood in the Legislative Assembly, with unanimous support from all political parties, to apologize for the wrongful arrest, trial and hanging of the six chiefs and to fully exonerate them of any crime or wrongdoing, to the extent of the province's power," said chief Joe Alphonse, leader of the Tl'etinqox Government and chair of the Tsilhqot'in National Government (a coalition of six neighbouring First Nations).

"The Law Society is right to admit to past mistakes and get rid of this monument to injustice and symbol of B.C.'s colonial past," Alphonse added. "The Tsilhqot'in Nation honours our war chiefs Lhats'as'in, Biyil, Tilaghed, Taged, Chayses and Ahan for their courage and sacrifice. They were heroes who defended their territory and traditional way of life against a foreign aggressor. In this time of truth and reconciliation, indigenous history and experiences can no longer be ignored."