In a few short months, local researchers will have access to information unlike ever before.

The University of Northern B.C. is building a Statistics Canada Research Data Centre. The small room, tucked into the entrance of its library, is almost fully furnished save for four computers that will give it a direct line into confidential microdata owned by the government agency.

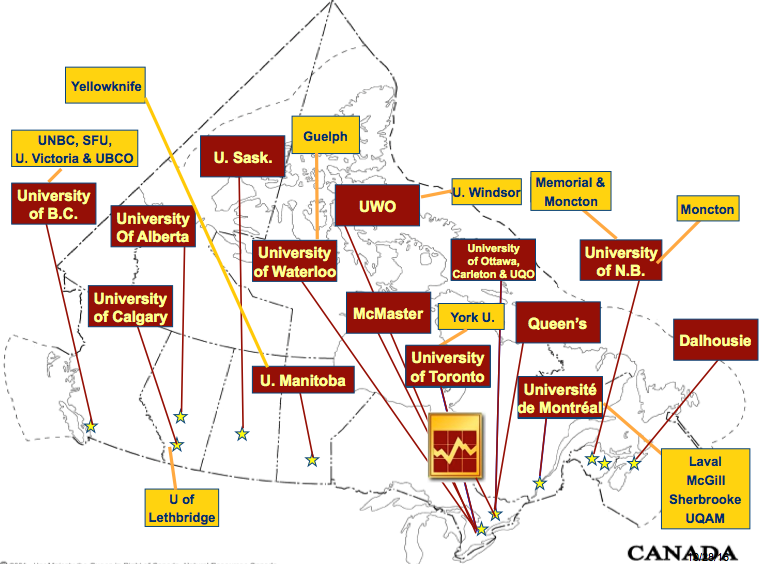

It will be one of 31 research locations in Canada and five in B.C. It will be Canada's second most northern site, south only to Yellowknife's in the Institute for Circumpolar Health Research.

Now the new centre's academic director won't have to travel to Edmonton or Vancouver to do her work. Before Cindy Hardy spent days at a time in those far-off centres, often doing several costly return trips for one study.

The whole time Hardy stands in the new room, she wears a wide grin and her sentences are punctuated by laughter.

Being a researcher, she explains, is like having permission to play all the time.

With the data centre in Prince George, "it's like having the sandbox open."

Before researchers like her can jump in - likely by the end of December or January - the equipment needs to arrive, get installed and inspected by Statistics Canada to ensure it's secure. But it still feels very close to Hardy since "RDC@UNBC" has been years in the making.

"The data sets are fabulous. As a researcher you can't ask for better... They're beautifully designed and set up, the sample is good... (It's a) good representative sample of Canadians," says Hardy, who credits now retired data librarian Gail Curry for pushing the project for so many years and current librarian Allan Wilson for continuing those efforts.

The startup costs are about $67,000 and annual operating costs are about $64,000.

In the north, it can be difficult getting samples that are large enough and representative of the population, which Hardy hopes this can help solve.

"An individual researcher can't do that kind of data collection," says Hardy, who as a developmental psychologist loves a longitudinal study that follows children from birth to age 16.

The public use files available outside of these centres have all identifiers eliminated. That affects community level work because most of the geographic information is removed "with the exception, in most cases, of the province and health region where the respondent resides," says Statistics Canada.

Hardy is planning presentations to show datasets researchers can mine - all touching on social issues - like surveys of perceptions of neighbourhood environments, blood samples for measuring exposure to toxins, drug abuse, and census data.

A lot of the Statistics Canada surveys are health-related - a boon for Northern Health analysts.

"It just strengthens our ability to understand the environment in which we work in the north. It brings the population data, particularly," says Fraser Bell, the health authority's vice president of planning, quality and information management.

"You can get aggregates of data publicly but to have the access through the research partnerships that we're involved into this kind of information... will be a real advancement."

A strong local university in the north is good for the north, says Bell, praising its leadership and work to involve Northern Health as well as the Northern Medical Program and other local partners over the last two years.

"With these partnerships it's so heartening to see a vision realized," Bell says. "Especially in the north research is done collaboratively. It very seldom is done by researchers in isolation."

Hardy estimates about six UNBC professors have used a data centre before, but knows of several in line already for the resource. Once the computers are set up only those who are trained, have approved projects and have sworn an oath of secrecy, will be allowed to punch in the pass code locking everyone else out. It can't be used by the police or for commercial purposes. The room also blocks wifi signals and the system connects only to Statistics Canada servers.

"It's a very unique process. We don't encounter anything like this in our research," says Hardy.

Any notes taken in those rooms must stay and academics leave only with the final product, an output that is reviewed by a Statistics Canada analyst to ensure no confidential information leaves the room.

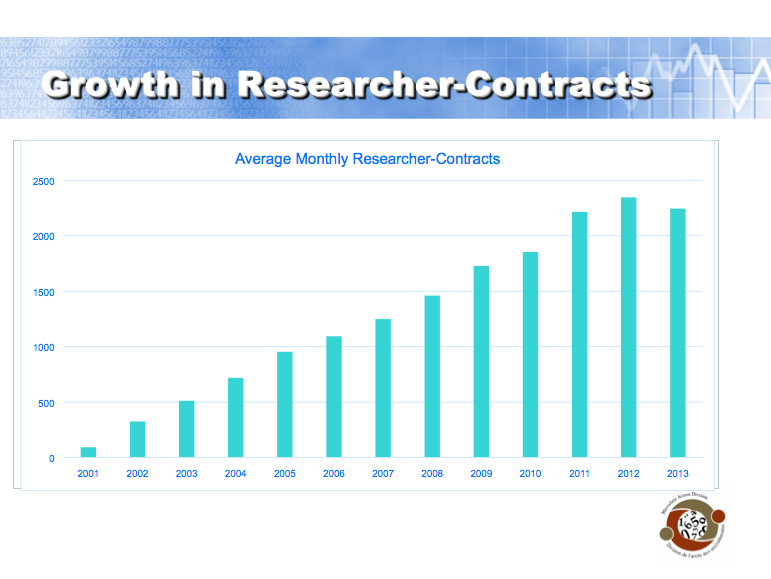

The Canadian Research Data Centre Network was established in 2000, when the first centre opened at McMaster University. In September, the federal government announced $14.5 million in renewed funding for the network, which includes more than 1,600 researchers.

"We are a pan-Canadian organization producing world-class research," says Joe Difrancesco, the networks operations manager.

"The research coming out of the universities is fundamental to impacting public policy to better the lives of Canadians from coast to coast."

The City of Prince George's manager of social development says the data centre will help its efforts around health and well-being for children and families and a collective impact approach to achieve large-scale social change.

"One of the elements of collective impact is good baseline data and ongoing tracking of data so you can know if you've made progress towards the achievement of your vision," says Chris Bone.

She's particularly interested in food security and to see if they can access neighbourhood-specific rates of poverty.

While the city can get high level data from public Statistic Canada files, she sees a couple issues with how it works.

"Sometimes it's such an aggregate number it's not actually valuable when you're trying to target a desired outcome," she said and "often it doesn't relate to neighbourhood or things we need."

It also creates more opportunity for the city to strengthen its relationship with UNBC, she said, and work with researchers that understand the Prince George context.

That's exactly it, says Hardy.

"We need more research about what's going on in northern B.C. We don't know enough about what's actually going on in the ground," she says, and while there are some gaps when it comes to rural and remote communities more research about the north by the north is good for the region.

"That's what the whole idea is: to increase the number of researchers... increase the quality of research and volume."