Climate change could contribute to bobcat populations shifting north and one B.C. student is turning to citizen science to help prove his hypothesis.

Before T.J. Gooliaff started his research in September, he believed the bobcat's northern limit was Williams Lake but conversations with foresters, trappers and residents have reported sightings in Quesnel, Prince George and Houston.

"I jumped out of my chair when those photos were sent to me," said Gooliaff, a 24-year-old biology masters student at University of British Columbia Okanagan, working with associate professor Karen Hodges.

"All across the planet species are moving northwards toward the poles in response to climate change," said Gooliaff, adding he's also looking at lynx to see how the territories compare and overlap. "Because bobcat and lynx are so climate sensitive, we think that they're moving with climate change."

Earlier springs and lower snow levels mean potential for more suitable habitat options in other areas in B.C.

"I hypothesize that bobcats have moved northwards and into higher elevations," he said.

The River Forecast Centre's June report said this season's melt in B.C. is three to four weeks ahead of normal after a warm winter. In January, a University of Northern B.C. study showed the volume of the mountain snowpack feeding B.C.'s largest watershed - the Fraser River Basin - has dropped by almost one fifth over a six-decade period.

Gooliaff is calling for photos of bobcats and lynx from all "corners of the province" to help map the distribution of the species. He's targeting Prince George in particular because preliminary findings suggest that the bobcat "front" is in the region.

"We think that the northern limit is somewhere between Prince George and Quesnel," said Gooliaff, who is looking at historical records, track data and maps to try and determine previous patterns. That might be difficult to pin down. "No one's ever done a study to try and figure out their distributions."

Any photo that might show a lynx or bobcat will help his research. Even if it's blurry, dark or shows a partial image, he just needs a date and location. So far, he has a library of 3,000 photos.

"We still need lots more," said Gooliaff, who expects to keep conducting research for at least six more months. "The more the better."

Historically, lynx and bobcats were separated by snow depth, with the small-pawed bobcats keeping south.

"They haven't really overlapped their ranges too much," he said, but that may be changing. While neither are endangered, a change in their typical territory would be another indicator of the impact of climate change.

"We're trying to figure out if (lynx) are contracting a bit," he said, adding they are found in boreal forests across Canada and Alaska, as well as the mountain ranges extending south into the western states.

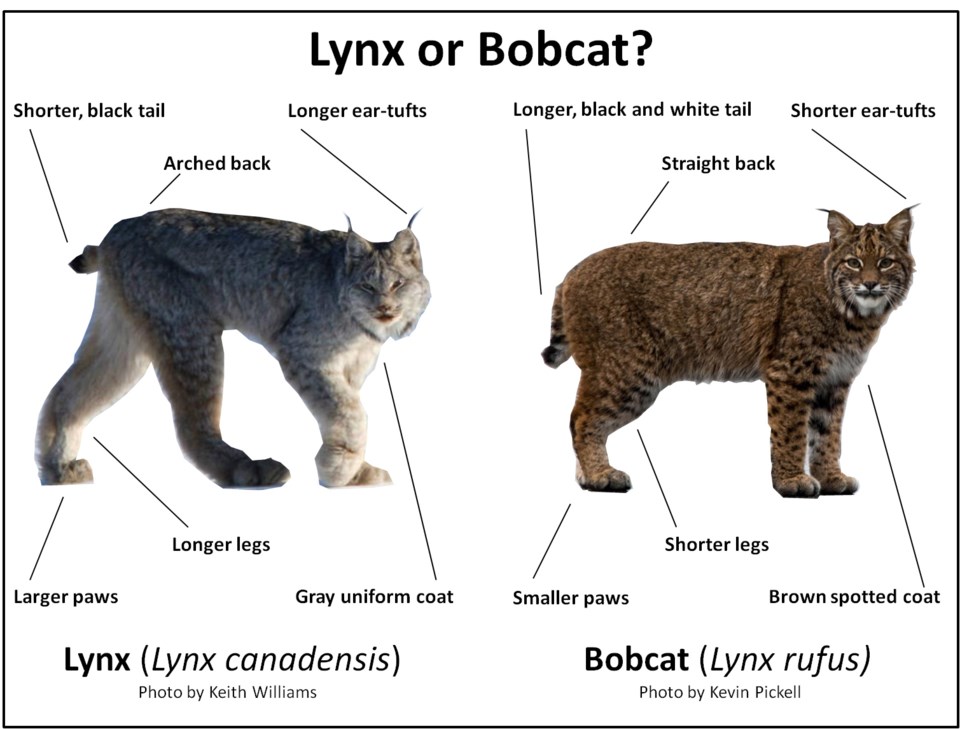

Their long legs and large paws mean they can travel across deep snow, unlike the heavier bobcats, which sink in. Often people mistake the two, though Gooliaff has a graphic that points to the bobcat's shorter ear tufts, shorter legs, brown spots and longer tail as good indicators.

To help with Gooliaff's research, email [email protected] any photos that could be lynx or bobcat along with the date and location. Photos will not be published without permission, he said, and photographers will retain ownership of their photos.